Most biographies and many books start off with a preface, then an introduction follows, and sometimes even an inaugural chapter, but, Gentle Reader, if you are like myself you will often skip these parts in your rush to get to the real substance of the thing. We Americans are busy people,

you will say, so never mind the fanfare and build up, just give us the real pièce de resistance without any extra dressing.

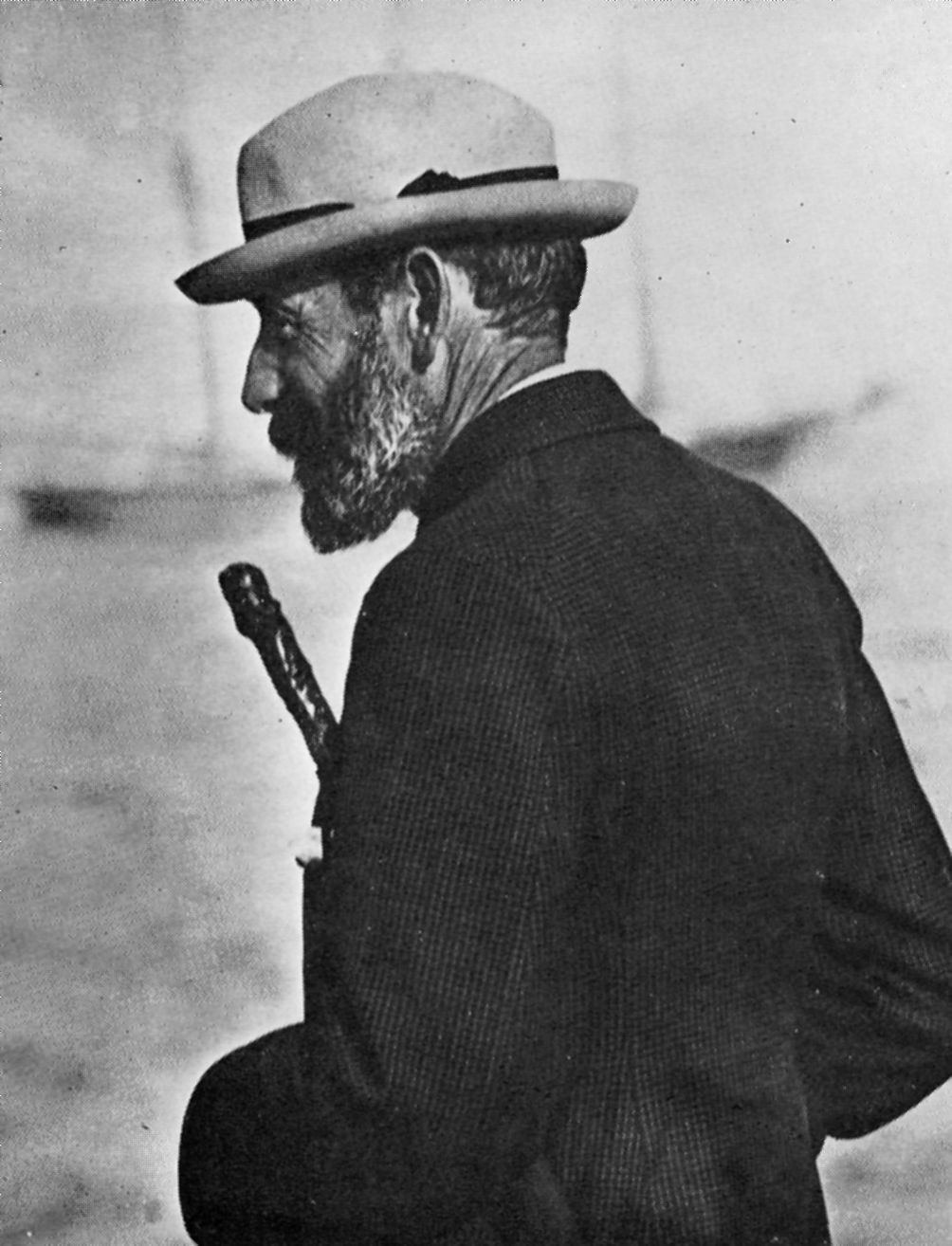

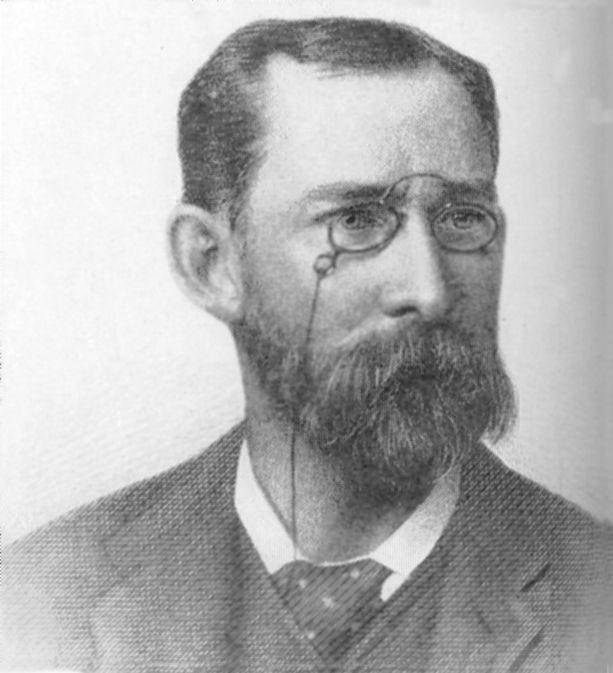

There is another reason also for my abruptness, and that is that our subject, Mr. Herreshoff, was very direct, straightforward and, at times, even blunt in his manner. He used no fanfare or mannerisms; in fact I think we may say his most outstanding characteristics were his direct acting mind and his love for the naked truth. He certainly had no patience with the shams, deceits, and confusions which prevent most of us from seeing clearly or thinking logically.

I believe he would say of this book, or any other for that matter: Why have an introduction? If you have anything to say, say it. There is no need of explaining why we are writing it. The text, if it is any good, will make that obvious.

I am sure he would say: Never mind about telling what a wonderful book this is to be, for the reader will decide that for himself after he has turned the last page.

But, Gentle Reader, I am entirely inadequate as a writer to take you directly to the crux of the matter. So, unfortunately, I must make some of the excuses generally found in an introduction, and I want to state quite clearly that this is no writing to be judged by the gentlemen who have studied the art of composition at either of the Cambridges. No, surely this will be no sublime composition where, for the form of the thing, its perfect balance of sentence—its cadence, if you like—the author has sacrificed the subject matter to achieve some accepted style. Instead, it is a simple writing intended only to describe the life work of Mr. Herreshoff, and, if possible, to correct several myths and falsehoods which have sprung up around his life.

While I am quite aware that such a prosaic attempt will not meet with the popular opinion of what a biography should be, still on the whole it may in this form be of more use to the student than some writing intended to amuse rather than to instruct, though at the present time it seems the custom of the biographer to dig out all the dirt, sordidness, and eccentricity of his subject and lay it before the reader.

For instance, each biography of Thoreau, as it comes out, makes him out to be more and more of a wild Indian instead of the original thinker that he was. But in the case of our subject, Mr. Herreshoff, I believe we can find enough of interest to talk about without departing much from his life's work.

As the time at which an individual is born, or rather educated, has nearly as much effect on his character as environment itself, we have called this first chapter, The Time and the Place,

and while this writer, like many others, believes that inheritance dominates all other factors in forming character, he has chosen the time and the place as the best medium of introducing Mr. Herreshoff and has taken later chapters to describe his inheritance and education.

As for the time, Nathanael Greene Herreshoff was born in 1848, and to be more exact on March 18 of that year which, strange to say, is a little over one hundred years ago from this writing. To those interested in yachting, it might be mentioned that this was three years before the America went to England to race for the Queen's Cup. It was a period about half way between the Mexican and Civil wars, and a time in this country when the various industries were employing many more people than previously in the manufacture of textile machinery, agricultural implements, fire arms; and the clock makers were setting up large factories and working out the technique of mass production. This certainly was a time when the stars were in a propitious position for accomplishment—a time quite different from the present when each man's arm seems turned against the other man.

Perhaps the time at which a person is educated is of more importance in forming his character, and that Mr. Herreshoff was between thirteen and seventeen years old during the Civil War no doubt had an effect on his convictions, for this great struggle of conscience and humanity against vested interests had rocked the whole country in a deadly argument. Those who were boys during this period were fed up with argument and as a class were short spoken; they were courageous, practical, and sometimes hard, and this is clearly shown in the portraits and daguerreotypes of the men of Mr. Herreshoff's age. Perhaps they had to be hard to face conditions after the Civil War, but at any rate these portraits show a quite different type of man from those of a decade before or a generation after.

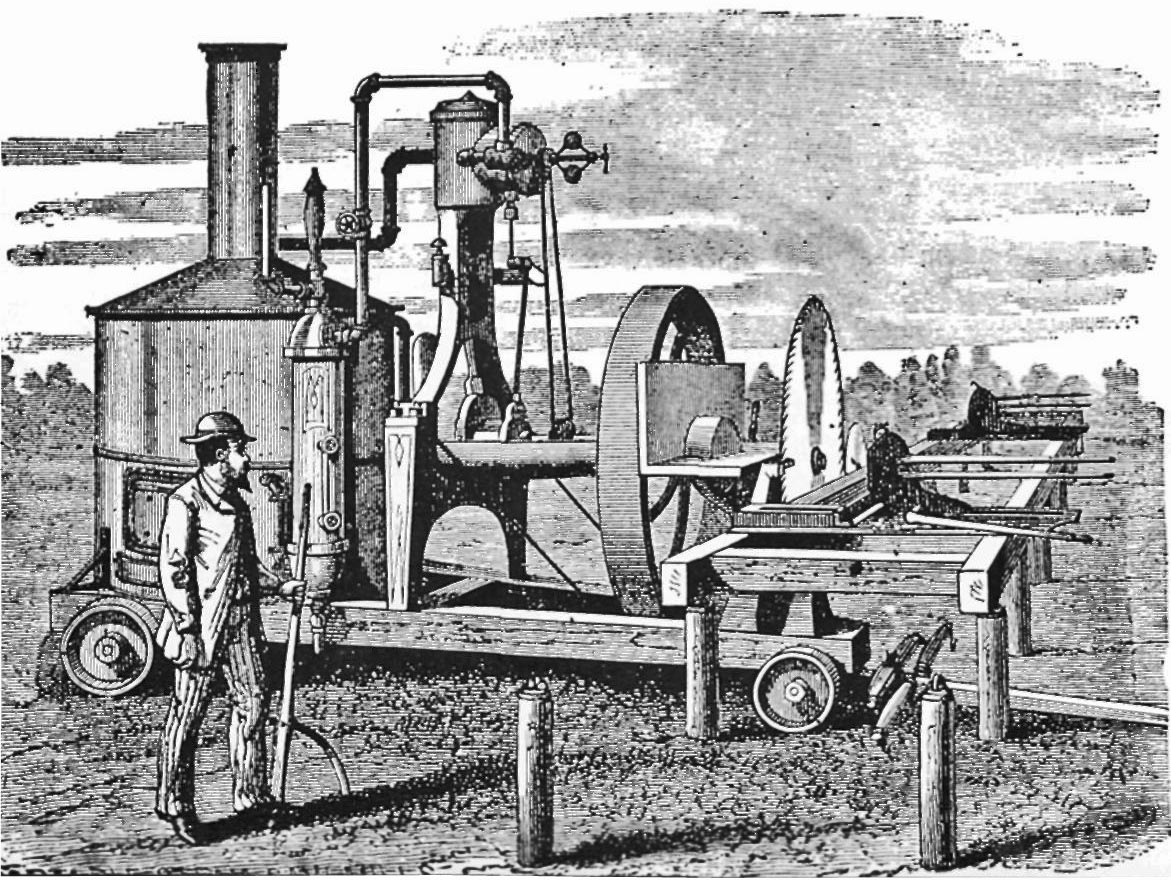

Before the Civil War this country had produced some really good writers and, several years before, some notable painters, but after the war the arts and literature were at their lowest ebb. At this time the steam engine was the reigning god, for no one then knew how to make dollars by electricity or gasoline. Commodore Vanderbilt in New York had made several million dollars with his steamships, which ran in most every direction, and he was beginning to take an interest in the iron horse or at least was buying up the rails the iron horse ran on in and out of New York. The steam engine was pumping water to most of the cities; it was running all factories not located near water power; it was sawing lumber and pumping out mines.

During the eighteen forties and fifties fast ship-rigged vessels, generally called "clipper ships," were developed both for carrying passengers to California during the gold rush and for shipping tea from China. To quote from A. H. Clark's book, The Clipper Ship Era, "The building of clipper ships in the United States reached its zenith in 1853. In that year forty-eight clippers were added to the California fleet and the wild excitement of building, owning, and racing these splendid ships was at its height."

After the Civil War, however, the steamship was so successfully taking the place of the clipper that practically no more clipper ships were built in this country. The steamer passage across the Atlantic was being spoken of as the Atlantic Ferry, and although for several years to come the sailing ships held the records for crossings, particularly running to the eastward, the steamer with sail as auxiliary power was making by far the most regularly scheduled passages.

It is little wonder that a youth brought up in a seaport in those times should have had thoughts mostly about sail and steam, and as many boys of a later generation were to dream of electricity, the internal combustion engine, and the airplane, young N. G. Herreshoff was dreaming about sail and steam.

Now that we have considered the time of Mr. Herreshoff's boyhood we should look at the place, for there is no doubt that boyhood associations, and the traditions of one's home town, have a marked effect on one's later career or course of action.

The place, Bristol, Rhode Island, where our subject was born, was one of our old seaports before vessels became so large that they required more draft, and although the old town had not been founded until about 1680 it soon went into shipping, for by 1690 it seems to have had fifteen of its vessels engaged in foreign trade. Bristol had originally been a part of the Plymouth colonies, made up of the three counties of Plymouth, Barnstable and Bristol, but the Bristol lands were inhabited mostly by Indians. At first Massasoit was the Indian chief of this district, and until his death in 1662 he remained friendly and faithful to the Plymouth Colony. He was succeeded by his son, Wamsutta, who reigned but a short time when Massasoit's second son, Philip, became chief of the Wampanoag tribe. Philip, although he was said to be partly of white blood, hated the English and started to war against them in 1675, but he was driven to a retreat at Mount Hope within the present township of Bristol, where he was shot and killed in 1676.

After King Philip's War it became practical to settle this region, so four wealthy Englishmen, temporarily residing in Boston, purchased about seven thousand acres of that part of Bristol County that borders on Narragansett Bay which had previously been called the Mount Hope Lands. These four original settlers or proprietors were men of means and apparently had good educations, for they laid the town out in a grand way with broad parallel streets as if planning a city. So far as I know, Bristol is one of the oldest New England towns that originally had straight streets for, as they say, most other towns built their streets along cowpaths. It is said that the founders laid the town out to be a seaport and that they hoped Bristol would be the shipping point for southern Massachusetts, as old Bristol in England was the shipping port for the western part of that country. But I fear one of the reasons the Bristolians took so suddenly to the water was that the soil of Bristol was not particularly fertile; its dry lands were stony and its low lands boggy, but I have no intention to write a history of the town and only want to explain the reason for its nautical inclination. I cannot refrain, however, from saying something about the people of Rhode Island, for in many ways they were quite different from the Puritans at Plymouth. And while it has been said that Bristol originally was a part of the Plymouth Colony, this was before it was settled. After it was settled it belonged to the Massachusetts Bay Colony until 1747 when it became a part of more liberal-minded Rhode Island.

But the early Bristol people were intimately connected with those of Boston during the first seventy years of Bristol's settlement, and the trail, or road, between the two places was called— at least for part of its way—the Anawan Trail for it went by Anawan Rock where the friendly Indian, Anawan, lived. Many of the early Rhode Islanders came from Boston and, as some said, left it for conscience sake, not liking the narrow Puritans or the witch-burning Salemites. However, many of the settlers around Newport and Kingston in South County were well-to-do English gentlemen who set up large farms and country estates with handsome manor houses. History relates that several of these families came over to raise horses and at a very early date they developed a famous breed of horses called a Narragansett Pacer. By 1686 Bristol was shipping these horses to South America and the West Indies.

These Rhode Islanders were not religious fanatics or fugitives from persecution; very few of them were connected with the renegades who had murdered Charles I and foisted the Commonwealth and Cromwell on the people. Free thought and religious freedom were allowed in the state, and although the Church of England, or what was spoken of as the Episcopalian faith during the Revolution, was the most respected church in the state, almost all other religions were represented, including numerous Quakers, and one of the proofs of this religious tolerance is that the first synagogue in America was located at Newport. So the people as a whole were more worldly than those of Massachusetts. They lived, dressed, ate, and I might say drank, like the European gentlemen of that time. There was no danger in Rhode Island of being burned as a witch if someone did not like your religion or coveted your property.

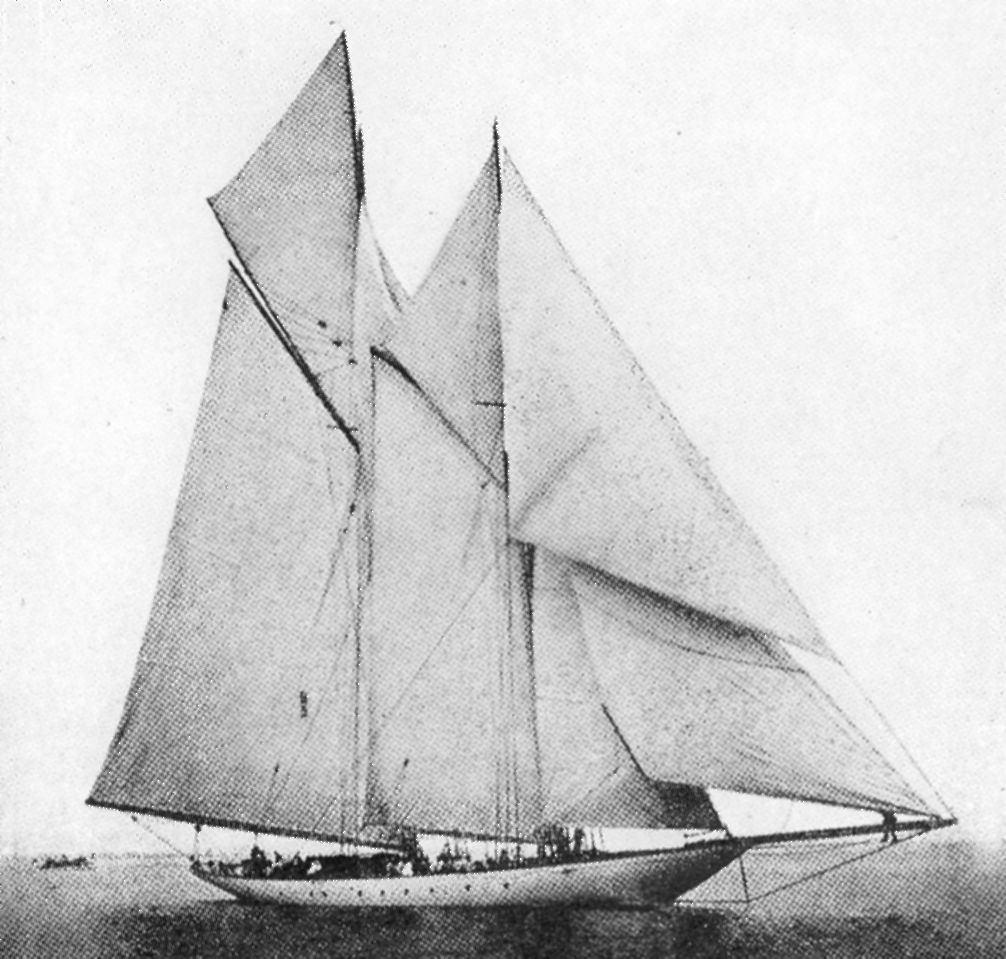

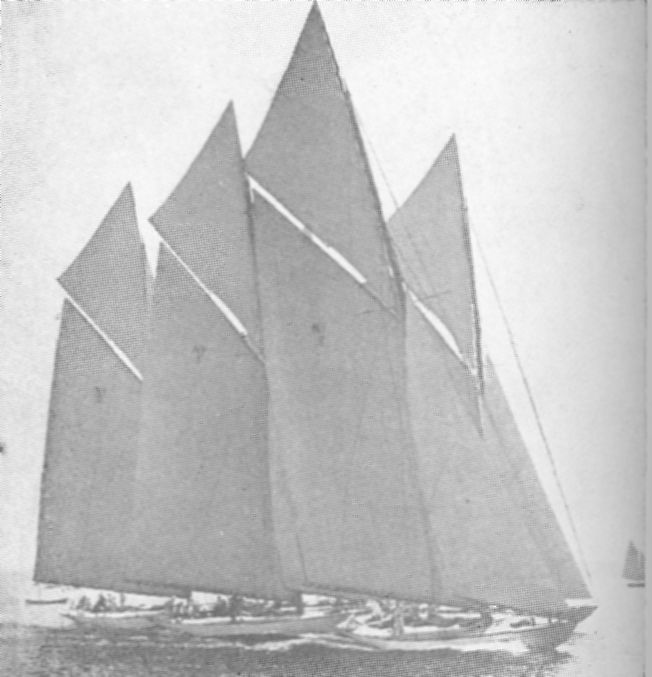

So with their worldliness they soon went into commerce, shipping, privateering, and running slave ships. The latter two activities called for fast vessels, and it is my opinion that the Rhode Islanders developed the world's fastest topsail schooners and brigs around 1800. Many of the slavers hailed from Bristol and between 1700 and 1800 there was no stigma associated with running slave ships. But the vessels had to be fast simply to transfer their living cargo from Africa with as little loss as possible, for only a slave in good condition brought a good price at the market. While it is true that Bristol ships landed slaves at Charleston, South Carolina, until about 1812 most of the slave running was done before that. Of the ships landing slaves in Charleston between 1804 and 1807—two hundred and two in all—seven hailed from Great Britain, three from France, one from Sweden, sixty-one from Charleston, and fifty-nine from Rhode Island; all other American ports accounted for but eight.

An ancestor of the writer is credited with owning ten slavers at Bristol in 1806 and having interest in four others. The Bristol slave ships sailed from their home port with a cargo of rum which they traded on the coast of Africa for slaves; then they ran to Cuba where the slaves were traded for a cargo of molasses, which in turn was taken to Bristol on the third leg of their triangular cruise. At Bristol there were quite extensive rum distilleries which are said to have distilled two hundred gallons a day in 1800.

However, it was not until after about 1820, when English and American men-of-war were suppressing the slave trade, that the horrors of the middle passage became notorious. At that time it is believed some slave ships disgorged, or threw overboard, their whole cargo of slaves so as not to be caught with this contraband on board. It is said that at times the whole shipment of slaves were shackled to an anchor chain and heaved overboard at once. This was done so none could be found floating by the overtaking revenue cutters. Although after the War of 1812 slave running was very profitable, it was looked on as a form of piracy and the crew of the slave ships were subject to capital punishment if caught. I believe few, if any, slavers sailed out of Narragansett Bay after 1812.

The slave ships that sailed from Bristol were quite small, probably mostly under a hundred tons; they were of light build and carried large sail area. Their rig was mostly topsail schooner and brig, and they were undoubtedly remarkably fast.

But there was another type of fast sailer being built in the Bay and this was the Colonial Privateer. Rhode Island produced more of these ships, which sailed and fought under the British flag, than any other of the colonies, and it is said that between 1700 and the Revolution one hundred eighty privateers were built or fitted out in the Bay. The author's great-great-uncle was the captain of one named Prince Charles of Lorraine which was particularly active in the war of her time between France and England and among other activities, in 1744, ransacked and plundered the French settlements along the coast of French Guiana much to the profit of his owner and himself.

These privateers of Narragansett Bay were lightly built and depended on their speed for escape or capture. Their usual mode of attack, even if it was a considerably larger vessel, was to lay to windward of their intended prize and with a long-range long gun drop a shot on her every quarter of an hour or so, all the time keeping just out of range of their antagonist's guns. In this way they made many captures without themselves being damaged, but this technique is only possible with a very fast and weatherly ship.

So, together with the practice of building slave ships and privateers for some hundred years, the art of designing and building fast sailing ships had been developed to a remarkably high degree in Narragansett Bay.

In the War of 1812 Bristol sent out several privateers and one of them, the Yankee, was the most successful of all American privateers. It is estimated she destroyed more than five million dollars of English shipping and no doubt brought to the old town of Bristol several fortunes for the profits of one cruise were divided as follows: owners, $223,313.10; captain, $15,789.69, and so on down to Jack Jibsheet and Cuffee Cockroach, the two colored cabin boys who shared respectively $738.19 and $1,121.88. These were large sums of money in those days.

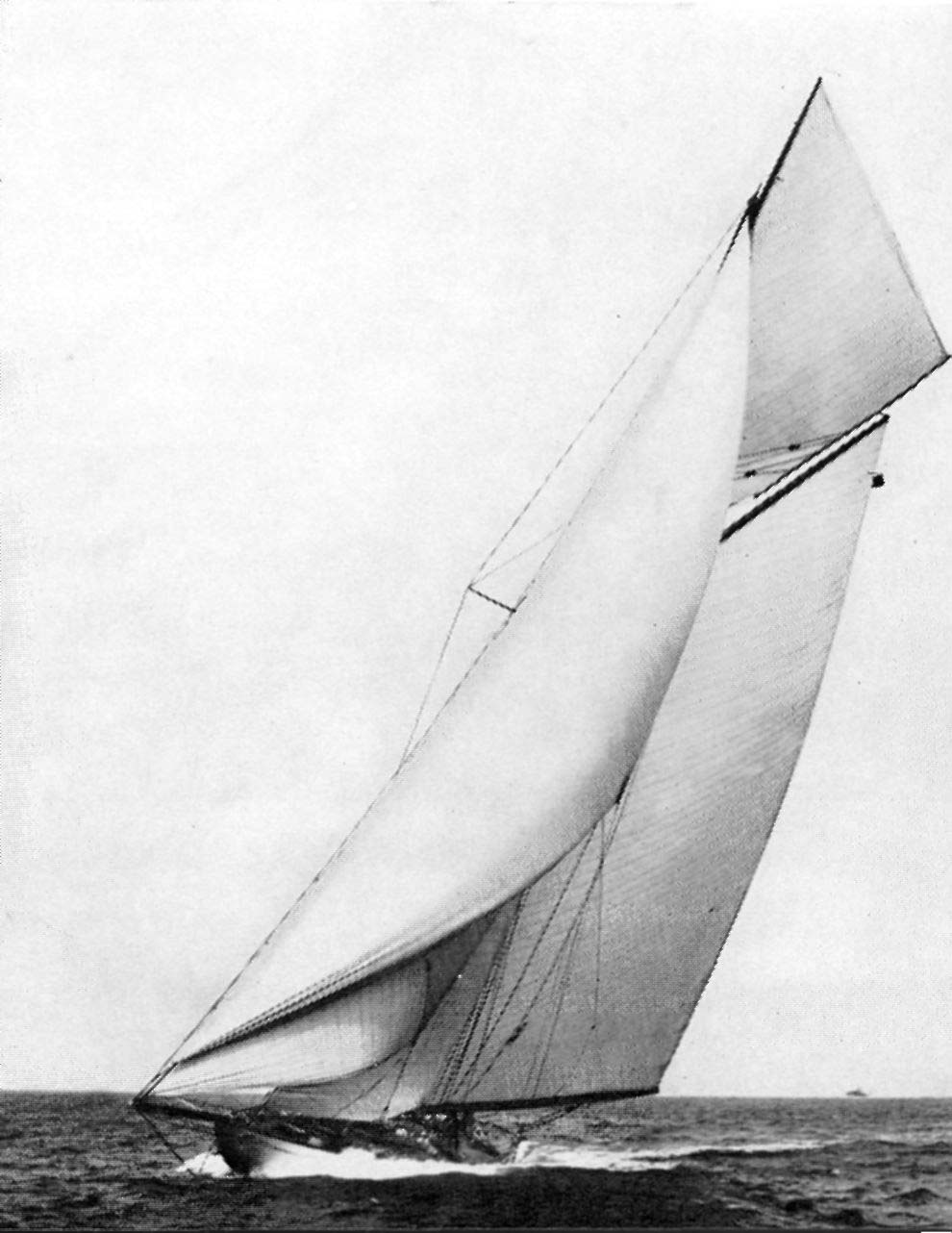

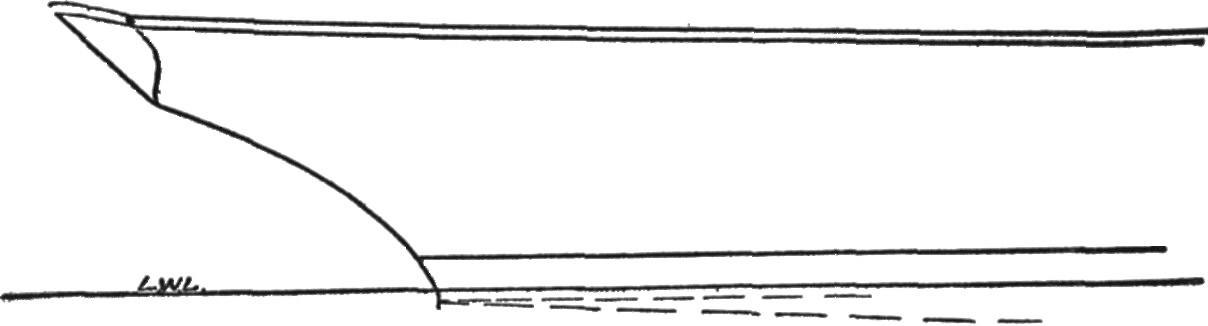

The Yankee was at sea less than three years as a privateer and made six cruises in that time; she undoubtedly brought more than a million dollars into the town, including some ships that her owners subsequently employed with profit as cargo vessels and whalers. Although there are practically no authentic plans, models, or lines of the Narragansett Bay privateers, I have had the Yankee described to me by a man whose father had seen her. She was said to have had a great deal of dead rise to her sections, and was fine on the waterline at both ends, and was said to have carried a large but very neat and light rig. Her best point of sailing, compared to other vessels of her time, was close hauled and, while we have no record of her speed under full sail in a chase, she did make a passage from Ascension to Cape St. Augustine, a distance of 1,200 miles, in seven and one half days. Another time she ran 3,500 miles in twenty-seven days. Most likely her speed when driven hard was in the neighborhood of fourteen miles an hour, or twelve knots.

Another privateer that hailed from Bristol was the Macdonough; she was larger than the Yankee and considered faster. While she took many prizes in the last year of the war, they all, I believe, were retaken by the many English cruisers along our coast so that as a privateer she was not profitable. She is said to have made a passage between Havana and Bristol in six days although becalmed one day of the passage. The Macdonough was later sold to Cuban owners and became a slaver.

After the War of 1812 Bristol went in for whaling as well as general commerce, and in 1837 its whaling fleet numbered nineteen ships. Bristol continued building ships until about 1850, and between 1830 and 1856 sixty vessels were built and rigged there.

And this brings us up to N. G. Herreshoff's boyhood, and I must say he often spoke with great respect of the ship carpenters, boat-builders, riggers, block makers, and sail makers who were still working in the old town and many of whom, as a matter of fact, were the first employees in his brother John's boat yard which was started about 1856. All of his life Mr. Herreshoff bewailed the fact that he could never get their equals in his later employees, and as Herreshoff yachts were considered of the highest quality in the world, it would appear that the native Bristol workmen at the time of his boyhood were real artists.

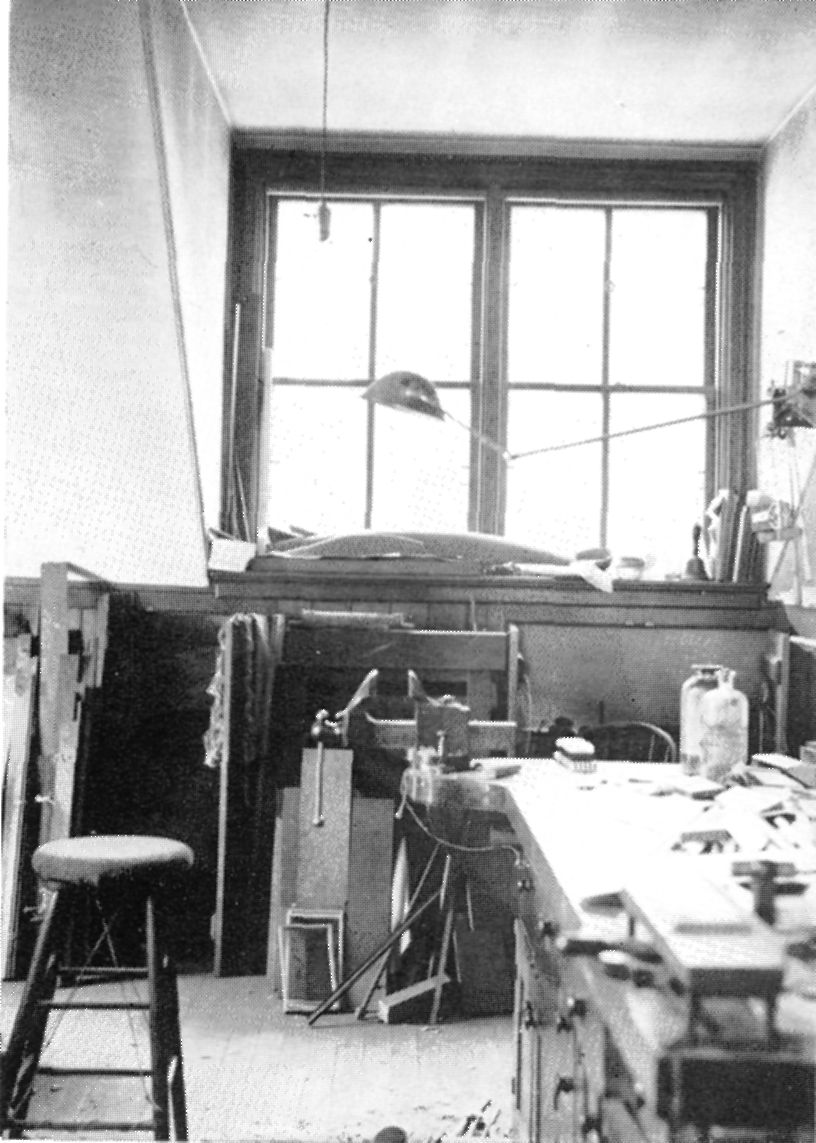

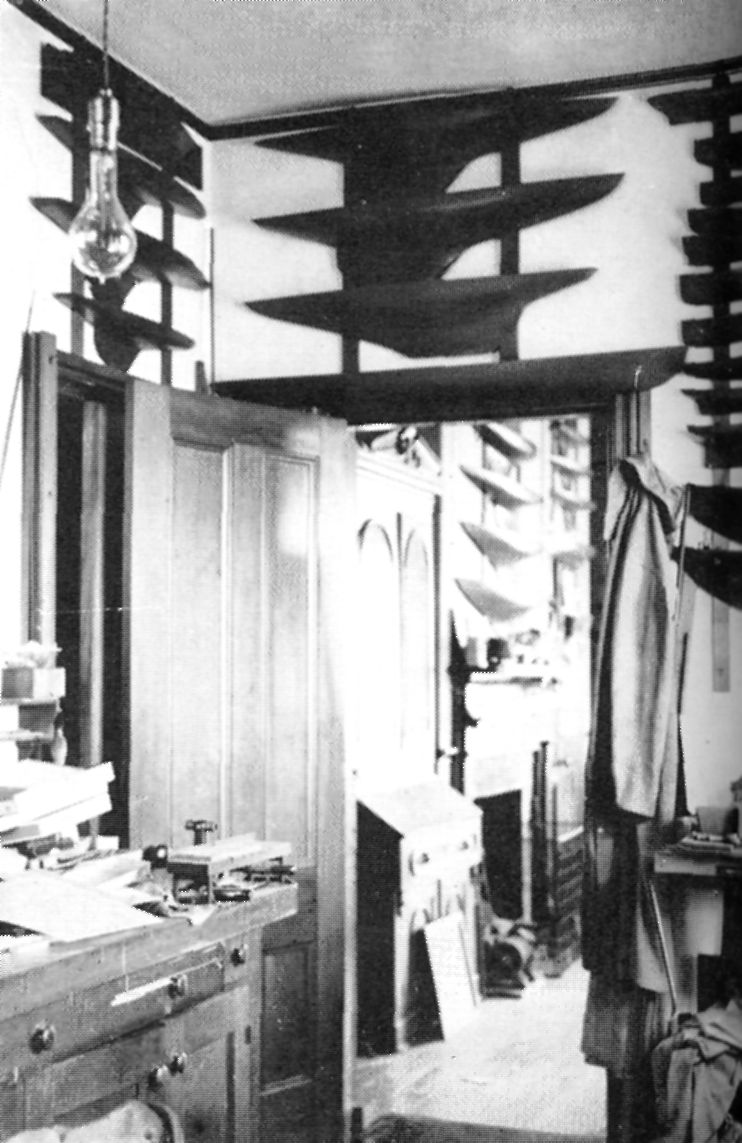

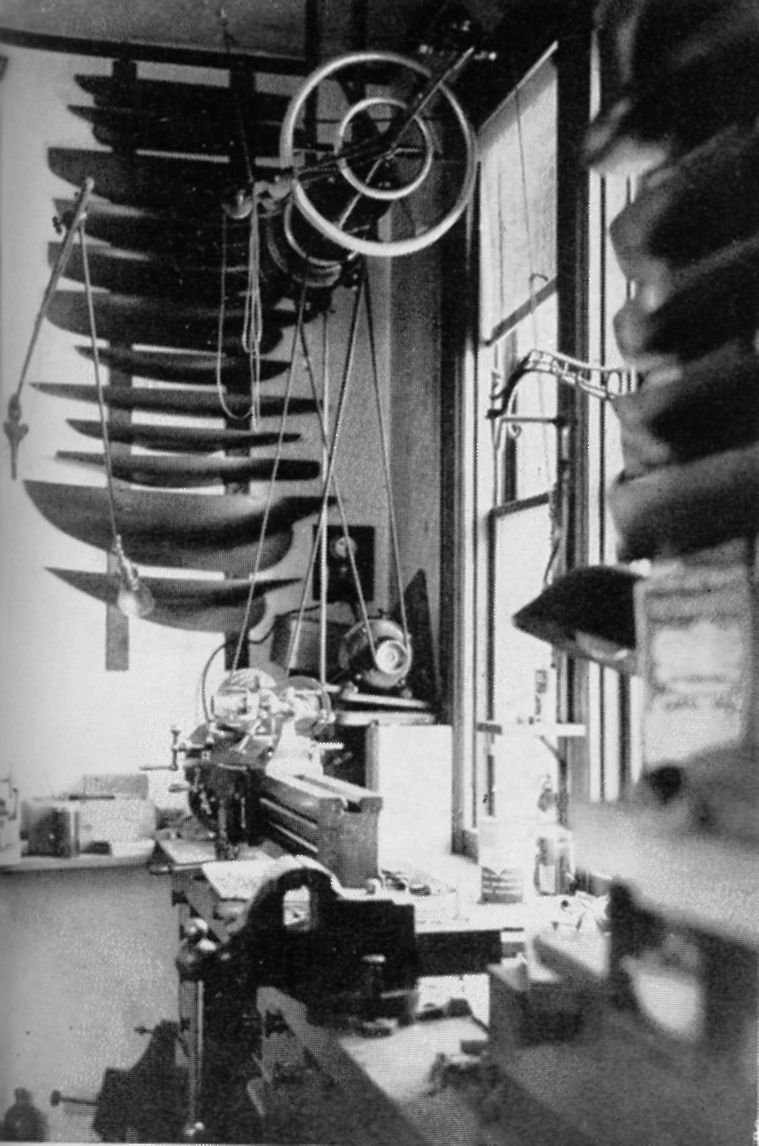

I have devoted all this space to the history of the town and the type of vessels built there because I believe that the traditions of Bristol and the craftsmen who lived there had a profound influence on Mr. Herreshoff's character. I know definitely he was one of the most skillful workers I have ever seen with the light shipbuilding tools, and I believe he acquired many of these skills in his childhood from his father and other native Bristolians. To me, a knowledge of how things are made seems the most important enlightenment a designer can have, for only then can he design things that are practical to make and only then will he have the complete confidence and respect of his workmen. There is no doubt that Mr. Herreshoff was a skilful mechanic at a very early age perhaps fifteen or sixteen, and all during his life he could direct his workmen, or explain to them in a very few words, the most practical method for accomplishing their particular tasks. One of the most remarkable features of all his designs was that the work could be made with the commercial materials available at the time and with simple tools and equipment. Perhaps no one knew better than he all of the tricks and techniques of pattern making, casting, forging, machining, sheet metal work, and general wood construction; and I refer here to these arts as practiced or performed by hand or with hand tools. While his later education, which we will speak of in a later chapter, increased his knowledge in all these arts, I cannot help but think it was mostly started with his early contact with Bristol mechanics, for time and again he would say to me in describing some technique or showing me how to do something: This is the way so-and-so used to do it,

naming some Bristol blacksmith, block maker, rigger, boatbuilder or sail maker of his boyhood. And while we have no space in this book to go into the history of cabinetmaking, clockmaking and ropemaking in Rhode Island, it is well known that these endeavors had reached a high state of perfection there in colonial times.

Even some of the Rhode Island gentlemen of leisure were mechanically minded and used small lathes for ivory turning and other ornamental turning, as many of the gentlemen of Europe had during the preceding century. All of these things had an effect on the traditions of the place and must have had a profound influence on molding the intellect of a boy of the time. In other words, this was a region that could mold a Yankee mechanic with greater perfection than places slightly to the westward where commercialism was the first consideration, and their famous product was the wooden nutmeg; while off to the eastward the finer arts had been looked down on by the descendants of the Puritans.

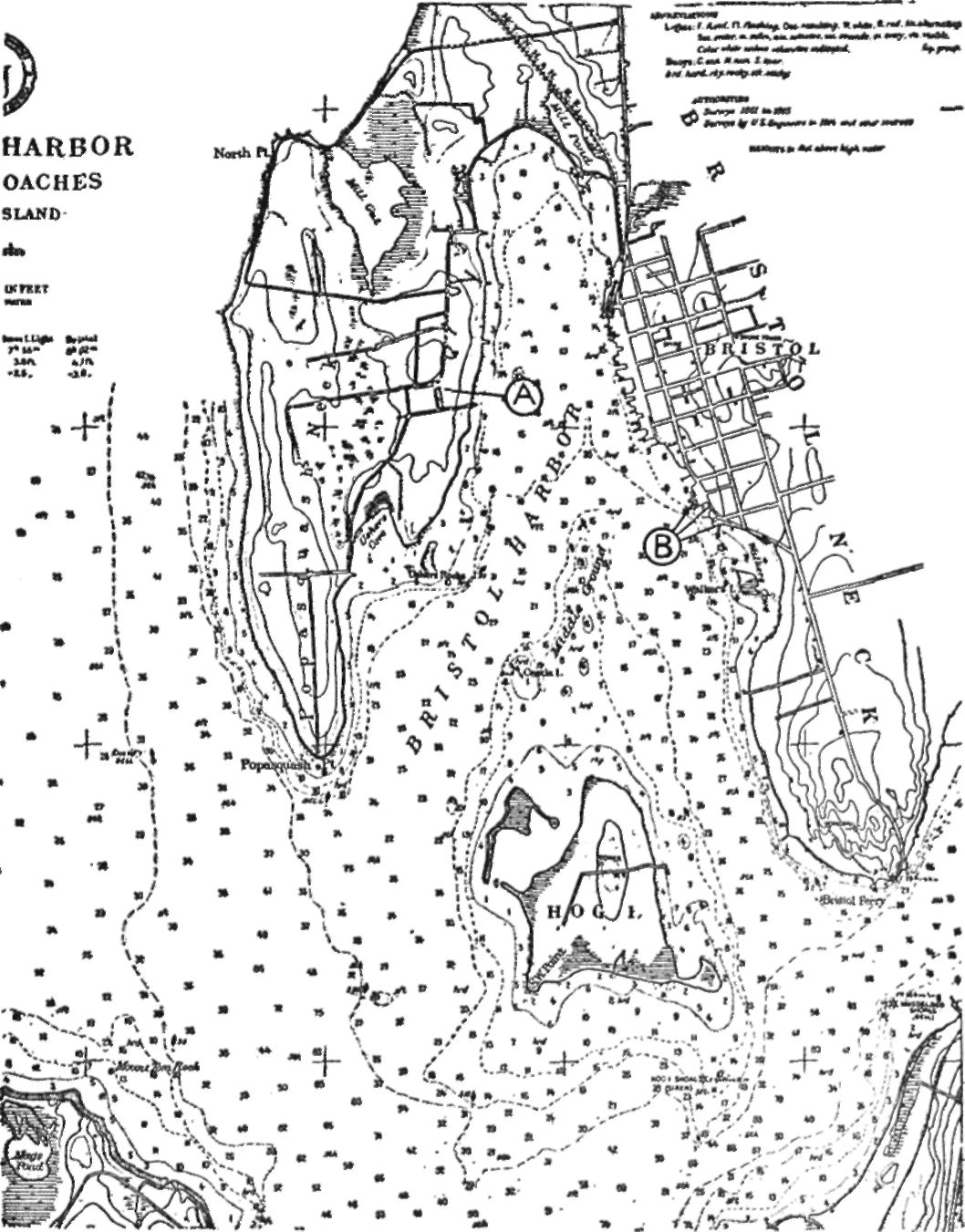

But we should now look at the geography of the place for perhaps the principal influences of environment are geographical, that is, climate, location, etc. The town of Bristol is located on a peninsula which, as it protrudes southward, approaches the center of Narragansett Bay. This neck of land in some ways is shaped like a lobster claw, with Bristol harbor the space between the jaws, and as the land narrows in toward the north, at what might be called the wrist of the claw, the town is nearly surrounded by water. While it cannot be said that there is any high land in the neighborhood, still this region is of a rolling nature as if leveled off and slightly gouged out in the glacial period. From the slightly elevated land back of the town one can command a panorama of some interest for, if not grand or inspiring, it at least has a certain fascination for a sailor—before him are several islands, points and bays so arranged that one overlaps another in a way that awakens the imagination and forms a visual pull that cannot be resisted by the young Anglo-Saxon. Thus, for centuries the boys of the town have been drawn to the waters of the Bay by this ever present picture.

Off to the south lies the island of Rhode Island only separated from Bristol by a sheet of water half a mile wide. In former times there were several windmills on the island of Rhode Island and from Bristol they gave the scene a rather foreign aspect, but to a lover of Rhode Island johnnycakes the slowly revolving sails of these mills brought pleasant thoughts for the mills were grinding meal from Rhode Island white cap and Rhode Island golden cap corn. And if there is anything better than that for a steady diet this writer has never tasted it, for it can be consumed with pleasure in one form or another three times a day for three hundred and sixty-five days of the year. Johnnycakes, corn bread, brown bread, Indian pudding, scallops rolled in corn meal and fried in bacon fat in a skillet—yes, bless the Narragansett Indians who gave us this corn. It might be interesting to note here that our Mr. Herreshoff ate these johnnycakes seven eighths of the mornings of his life. I suppose I should apologize to the patient reader, but he would readily excuse me if he had been brought up in sight of those windmills.

Just to the westward of the island of Rhode Island is a fairly straight, sparkling strip of the Bay running in a compass course nearly south by west, clear to Newport, but this magnificent sheet of water is somewhat obscured from view by Hog Island which partly encloses the southern side of Bristol Harbor: otherwise Bristol Harbor would be quite exposed to southerly winds. Then more to the westward, and perhaps bearing southwest, lies Prudence Island—an island six miles long—and while Prudence cuts off much of the view farther to the southwest, still in places over its lower lands the more distant country shows up in blues, greens, and browns depending on the season. Surely, on a clear day after a snowstorm the distant colors are lovely.

On the west side of Bristol Harbor lies Popasquash Neck, and this was the birthplace of Nathanael Greene Herreshoff. But we must locate Bristol more clearly in the mind of the reader and perhaps partly account for its becoming so successful as a yacht-building locality. Bristol is ten miles north of Newport, and Newport is one of the best yacht-racing locations in the world. Bristol, you might say, is midway between New York and Boston. Boston is much nearer overland, but before the Cape Cod Canal was cut New York was not only closer by water but also much of the run to New York was in somewhat sheltered waters. So Bristol may have been quite near the center of yachting between 1850 and 1900 when yachting, to quite an extent, was confined to the region between Maine and the Chesapeake. Bristol in these times had excellent communications both by water and rail with our eastern cities, and at times coal, lumber and other yacht-building necessities were landed from schooners right onto the wharf of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company. Even in the writer's youth several varieties of excellent oak were felled within fifty miles of the town.

Bristol enjoys a mild climate compared to most New England towns. The northeast winter gales that rake the coast north of Cape Cod are rather tempered when they reach Bristol, and while the snowfall there is perhaps more than in places right on the ocean the snow is apt to be level and not drifted. Although the northwest gales roar across Bristol with the same velocity as other eastern towns, she never feels the icy blasts that come down the Hudson. The water in Narragansett Bay is some ten degrees warmer than that north of Cape Cod, and this seems to make the falls later and prolong the Indian summer at times almost to Christmas. In fact the pleasant weather of autumn in Bristol is only surpassed by that of Newport, Nantucket, and Provincetown which are even closer to the Gulf Stream.

The prevailing wind in Narragansett Bay is decidedly southwest, and in the spring it often blows a good breeze from that quarter day after day with tiring monotony. Though the temperature is not low, this chilly, damp breeze from the Atlantic keeps one in thick clothes until June. In the summer, however, this breeze, which blows nearly every afternoon, keeps Bristol delightfully cool, and when the breeze dies down at sunset and the heat of the day has passed, a quiet restfulness permeates the air. This was the time, in days gone by, when the good people of the town made their calls, for it was delightful in the balminess of the evenings to walk through the streets of the old town which in many places were a continuous bower or arbor formed by the branches of gigantic elms that met overhead some fifty feet above the street. These evening calls were in no way social engagements, but were simply the spontaneous desire of friends and relations to commune with one another, for throughout the town a genuine friendliness prevailed.

Perhaps the peculiar tranquility of the place was partly due to the subduing effect of the southwest wind and perhaps partly as a result of the good Bishop Griswold having long resided there, for his famous revivals of the eighteen twenties had changed the thoughts of many people from the worldliness of slave ship and privateering days to a thoughtful piety—a piety that not only called for an effort to prepare one's self for a future life, but more particularly to help one another in this life—for which he set the example in both his acts of kindness and his lessons in refined conversation. Even in my childhood the conversations of a summer evening were entirely devoid of sarcasm, contradiction, and boastfulness. Perhaps some of my readers will think this a stupid sort of conversation, but you will find that when people rich in experience and skillful in conversation get together there is never a moment of boredom. In these evening talks or visits the person speaking was never interrupted, and no one would have thought of contradiction. Thus the speaker could speak slowly with well-chosen words. He knew his listeners would wait for the full meaning of his sentences, and that each word would be carefully considered. The subject may have been the speaker's travels in Europe, or one of the ladies may have described her life in Latin America: perhaps a book of some significance was reviewed, but more often than not one of the older persons would tell anecdotes of past times. The men spoke in a kindly voice and the response of the ladies was in a low, soft and melodious tone. Even if the conversation took a genealogical turn, the ladies remained tranquil for they knew that Grandma at the end of the veranda could settle all questions without controversy, and as the moon rose above the eaves of the house and shone down on the old lady's face, as she sat in her cap and cashmere shawl, you could see that she had enjoyed the evening as well as anyone.

Refreshments were seldom served during these evening calls, and stimulants quite unnecessary for the fragrance of the flower gardens, at it permeated the summer night, was in itself slightly intoxicating. No doubt, if called for, a decanter of old Madeira could be found on the sideboard but even that could not have increased the natural feeling of well-being inherent in a Bristol summer evening.

On account of its mild summer weather Bristol had been a summer retreat for Bostonians since colonial times, and later some New Yorkers, who preferred rest and quiet to the gayer society of Newport, visited the town annually. The matrons of Bristol had no little reputation for hospitality, and, as managers of the kitchen, perhaps could not be excelled by any north of the Mason and Dixon line. For generations they had been collecting receipts of, and perfecting, the local dishes. In colonial times some of the larger houses of the town had expert colored cooks who may have been trained in Cuba during the slave running days. The early matrons of Bristol must have made many gastro-nomical experiments: they must have had a highly perfected sense of taste together with some originality for they have handed down to posterity several dishes not generally known outside of the town. To me, even a quahaug pie made by a Bristol cook of the old school seems far ahead of the best that English cooks can offer and far superior to the complicated concoctions of the French school.

Each season of the year brought forth its appropriate viands, one after the other, so that the menus of no two weeks of the year were alike. The Bristol housewife had Rhode Island greenings for her pies and apple slumps, Rhode Island Red poultry for roasting and for chicken pies, Rhode Island corn meal for at least a dozen dishes and, as a last resort, she could always fall back on a Rhode Island clam chowder with complete confidence. The fish of the Bay allowed a pleasant variety to the Friday meals, for hardly anything is nicer than a broiled squitegue or a baked tautog while scup in its season was as delightful to the palate as it was fun to catch. As for the shellfish that grew in the deep blue clam mud of the Bay, well, there is nothing like them anywhere else except in Buzzards Bay and that may be one reason that a clam chowder, a clam bake, or a clam pie cannot be made out of these regions. The scallops, quahaugs, and oysters used to be plentiful and particularly tasty.

But the fall of the year was when a Bristol kitchen gave off its most enticing odors, for one after another there were special field days for putting up,

as they used to say, pickles from green tomatoes, making grape jellies and grape jam from the large, fragrant wild grapes of the district. Then the quince jelly and quince preserves were put up; and after cold weather had set in and the pigs were killed, sausage meat was made, and the long and complicated process of making mince meat was undertaken, which at times took the best part of a week before the large crocks in the cellar were filled with this aromatic mixture which would make the filling of mince pies until springtime, and, by the way, kept getting better and better. Most every Bristol home of any consequence had its own vegetable garden, and the warm, damp summer nights of the place produced luscious vegetables. Particularly, the lima beans and sweet corn grew with a perfection of quality and richness of taste. Many of these gardens had a row of herbs so the Bristol matron usually was well supplied with thyme, sweet marjoram, summer savory, and sage; also peppers of various kinds which generations of practice had taught them to use so skillfully that the odor alone of Bristol cooking was not the least of its charm.

I would like the reader to understand that I have not told these things about Bristol in a boastful way simply because it happened to be the writer's birthplace, but I have tried to show that Bristol during Mr. Herreshoff's life was an ideal place for undisturbed work and rest, and that the people of the place had a certain refinement. But most of all I have tried to bring out why it was possible for our subject to have the best of food, and this last in itself no doubt had a most important effect on his great energy and long life.

This is the best description of the time and the place that the writer can make, and in the next chapter we will describe Mr. Herreshoff's ancestors and from now on refer to him as Captain Nat for that will help to distinguish him from other Herreshoffs that will be mentioned. Also Captain Nat was what he was called most of his life.

In former times genealogy was looked upon almost entirely as an exact chronological listing of births, marriages, and deaths, but today many people are more interested in what is commonly called eugenics, so in this chapter if there is some slight discrepancy in dates, or in the spelling of someone's name, I believe it will be of little consequence for it is the character or peculiarities of Captain Nat's forebears that are the most important. One of the complications is that his ancestors can be traced back many generations, and that in itself makes a multiplicity of things, so for the sake of the reader I will only describe those ancestors who I believe threw strong characteristics. And all the time I am quite conscious that anyone who writes on genealogical matters will be contradicted by some of the relatives of his subject. Yes, I can plainly hear some female relation saying in a high tone of voice, I never heard of such a thing! She wasn't his great-aunt at all, for she was nothing but his grandfather's sister.

And, as experience has shown, it is best not to answer these outbursts; the writer will continue that policy.

The first Herreshoff that we know about was a member of the famous bodyguards of Frederick the Great of Prussia who were famous for being large and handsome men. This must have been in about 1750. His name was Carl Friederich Herrschhoff (original spelling). In about 1760 he married Agnes Muller who was said to have been lovely in person and well equipped mentally. They had a son born in the year 1763 who was also named Carl Friederich Herrschhoff although he later changed the spelling of the name to Charles Frederick Herreshoff. Agnes Muller died soon after the birth of her son, and the father became melancholy and wandered away into Northern Italy and was never again heard from. The young Carl Friederich was cared for as a baby by two aunts, but later, when about eight years of age, was given into the full charge of a professor who lived in Potsdam. Frederick the Great often went to consult with this professor and there met the boy in whom he took a great interest for some reason or other, perhaps because he had known the parents. At any rate the king made arrangements to have him educated in a then famous school in Dessau where he studied for eight years and then came to this country in 1787 where he entered the importing business in New York City.

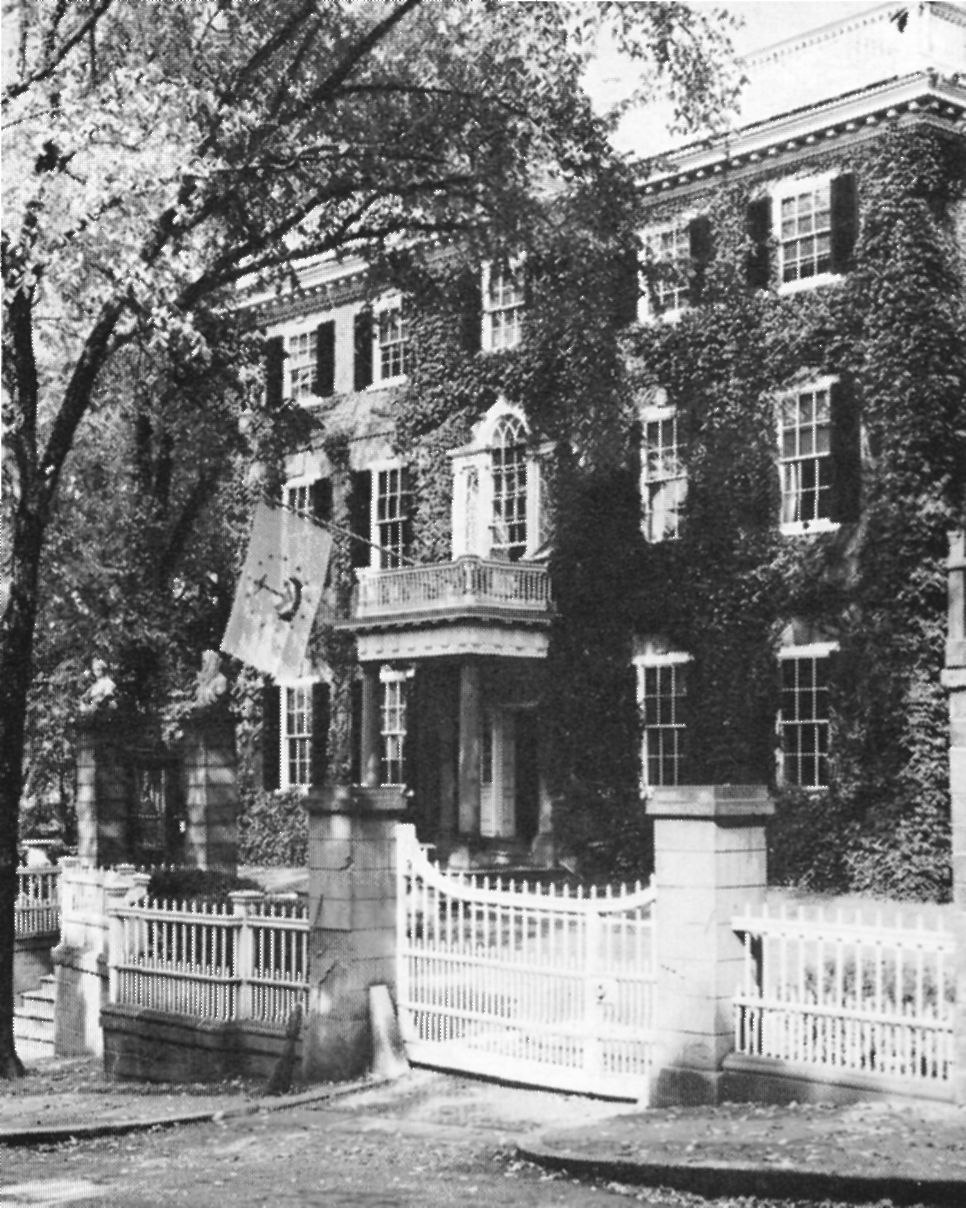

About 1793 he went to Providence, Rhode Island to confer on business matters with John Brown who was one of the leading merchants and shipowners of Providence. John Brown was impressed with the personal and mental attractions of young Herreshoff and took him to his home, the then new house on Power Street, which is now occupied by the Rhode Island Historical Society. Young Herreshoff, besides being a man of personal attraction, was a musician who sang as well as played on the flute. Sarah, the second daughter of John Brown, was also a musician so they sang and played together and became mutually attached. Their engagement at first was opposed by John Brown, which is not at all surprising, for young Herreshoff had no fortune other than a remarkably good education. But later, persuaded by his other daughter, Abby Francis, he consented to the marriage which was performed in the drawing room of the Power Street house on July 2, 1801.

The newly married pair, after living in several places, finally settled on one of the several country estates owned by John Brown. The one chosen was the Point Pleasant Farm on Popasquash Neck, Bristol, R.I. This piece of property and its colonial house had been owned by one Vassall who remained a Tory in the Revolutionary War so that the property was confiscated by the Rhode Island Assembly. During the Revolution it was occupied as a hospital for Rochambeau's soldiers, some of whom are buried on the property. In 1781 John Brown took this and other parcels of land in payment for money he had furnished to finance the Revolution. The house had been built in 1680 by Nathaniel Byfield, one of the original settlers of the town and a man of means. The house had more the style of a manor house than the usual colonial residence. There was a two-story hall running through the central part of the house terminating in large doors at each end. Near the house was a fair-sized brick building for the slaves and servants, and around the house there were several exotic trees which must have been planted at an early date. Some of these trees were varieties unknown to me, but the tulip trees had grown to the largest size I have ever seen. On the south side of the house was a well-sheltered flower garden, while on the east side a veranda looked out over Bristol Harbor and the town of Bristol beyond.

The original Carl Frederick, with what might be said to be a court education, was not adapted to life in America around 1800: he was said to have been a man of polished address, highly educated, an accomplished linguist in seven languages, and a good musician. He was variously employed by John Brown and died in 1819 while endeavoring to start an iron-smelting enterprise for him on his tract of land in Herkimer County, New York.

I have spoken at some length about the first American Herreshoff because several writers have said that Captain Nat was the son of a German engineer, and one said he was the son of a German mechanic, but the truth of the matter is that he belonged to the third generation of Herreshoffs in this country, and the first Herreshoff came over here before Germany was formed.

There were six children born to Carl Frederick and Sarah Brown Herreshoff between 1802 and 1812 and only one of them left descendants. This was Charles Frederick born in 1809 of whom we shall tell about later, but in the meantime perhaps we should review the Brown side of the family.

The first generation of Browns in America was Chad Brown and his wife, Elizabeth, who came over on the ship Martin, which arrived at Boston in July, 1638. It is possible that his religious views were not in harmony with the Massachusetts settlers for he soon went to Providence, Rhode Island, and there with twelve others signed the original compact and thus became a colleague of Roger Williams. Chad was the first surveyor of the town of Providence and the first ordained Baptist pastor. At other times, I suppose, he was farming, trading, or hunting like other pioneers. Roger Williams, in speaking of the dissensions that disrupted the peace of the early colonies, speaks of Chad Brown in this wise: The truth is that Chad Brown, that Holy man, now with God, and myself, brought the remaining after-comers and the first twelve to a one-ness by arbitration.

This perhaps was no little feat in those days of strong conscience, when the best of friends, brothers, sisters, or sons might suddenly become enemies for conscience sake. However, Rhode Island seems to have been settled without burning a martyr or dipping a witch. Somehow or other the Brown family in later years became prosperous and several of them were ship captains and shipowners until we get to the fifth generation of Browns in America, one of which was John Brown, born in 1736, and the great grandfather of Captain Nat. John Brown is said to have been a man of magnificent projects and extraordinary enterprise.

Though a wealthy merchant, and having larger interests at stake than most men, he was a patriotic leader in the struggle for American independence. He contributed substantial aid to the cause, which seems to have been appreciated by George Washington, for he presented John Brown with portraits of himself and Martha, portraits which were in Captain Nat's home. John Brown had made most of his fortune in shipping and ran a line of sailing ships directly to China and the East Indies. He was one of the principal owners of the Hope Furnace in Cranston, Rhode Island, which manufactured cannon for the Continental Army. He had the foresight to order his many ship captains to bring in gunpowder on their return voyages so that he was able to supply Washington's army at Cambridge, Massachusetts with this necessity when their supply was exhausted. He was the leader of the party that destroyed the British armed schooner Gaspée in Naragansett Bay on the tenth of June, 1772. Mr. A. DeWolf Howe, the New England historian, says that the first English blood of the Revolution was spilled in this affair, and while the Bostonians think their tea party was the first bold act of the war, the Rhode Islanders are proud of the burning of the Gaspée, so I will give the reader a first-hand account of this action written by one Ephraim Bowen.

An Account

Of the Capture and Burning of the British Schooner

Gaspée

In the year 1772, the British government had stationed at Newport, Rhode-Island, a sloop of war, with her tender, the schooner called the Gaspée, of eight guns, commanded by William Duddingston, a Lieutenant in the British Navy, for the purpose of preventing the clandestine landing of articles subject to the payment of duty. The Captain of this schooner made it his practice to stop and board all vessels entering or leaving the ports of Rhode-Island, or leaving Newport for Providence.

On the 10th day of June, 1772, Captain Thomas Lindsey left Newport in his packet for Providence, about noon, with the wind at north; and soon after the Gaspée was under sail, in pursuit of Lindsey, and continued the chase as far as Namcut Point (Now called Gaspée Point), which runs off from the farm in Warwick, about seven miles below Providence, and is now owned by Mr. John B. Francis, our late Governor. (Now a part of the Spring Green Farm, owned by Mrs. Frank Hale Brown). Lindsey was standing easterly, with the tide on ebb about two hours, when he hove about at the end of Namcut Point, and stood to the westward, and Duddingston in close chase, changed his course and ran on the Point near its end, and grounded. Lindsey continued in his course up the river, and arrived at Providence about sunset, when he immediately informed Mr. John Brown, one of our first and most respectable merchants, of the situation of the Gaspée. He immediately concluded that she would remain immovable until after midnight, and that now an opportunity offered of putting an end to the trouble and vexation she daily caused. Mr. Brown immediately resolved on her destruction; and he forthwith directed one of his trusty ship-masters to collect eight of the largest long-boats in the harbor, with five oars to each, to have the oars and rowlocks well muffled, to prevent noise, and to place them at Fenner's Wharf, directly opposite the dwelling of Mr. James Sabin, who kept a house of board and entertainment for gentlemen, being the same house purchased a few years after by the late Welcome Arnold; is now owned by, and is the residence of Colonel Richard J. Arnold, his son.

About the time of the shutting of the shops, soon after sunset, a man passed along the Main-street, beating a drum and informing the inhabitants of the fact that the Gaspée was aground on Namcut Point, and would not float off until 3 o'clock the next morning, and inviting those persons who felt a disposition to go and destroy that troublesome vessel, to repair in the evening to Mr. James Sabin's house. About 9 o'clock, I took my father's gun, and my powder-horn and bullets, and went to Mr. Sabin's, and found the southeast room full of people, where I loaded my gun; and all remained there till about 10 o'clock, some casting bullets in the kitchen, and others making arrangements for departure; when orders were given to cross the street to Fenner's Wharf, and embark, which soon took place, and a sea Captain acted as steerman of each boat, of which I recollect Captain Abraham Whipple, Captain John B. Hopkins, (with whom I embarked,) and Captain Benjamin Dunn. A line from right to left was soon formed, with Captain Whipple on the right, and Captain Hopkins on the right of the left wing.

The party thus proceeded till within about sixty yards of the Gaspée, when a sentinel hailed,

Who comes there?No answer. He hailed again, and no answer. In about a minute, Duddingston mounted the starboard gunwale in his shirt, and hailed—Who comes there?No answer. He hailed again, when Captain Whipple answered as follows:—I am the sheriff of the county of Kent, God Damn you; I have got a warrant to apprehend you, God Damn you; so surrender, God Damn you.I took my seat on the main thwart near the larboard rowlocks, with my gun by my right side, and facing forwards. As soon as Duddingston began to hail, Joseph Bucklin, who was standing on the main thwart by my side, said to me,

Ephe, reach me your gun, and I can kill that fellow.I reached it to him accordingly, when during Captain Whipple's replying, Bucklin fired and Duddingston fell; and Bucklin exclaimed,I have killed the rascal.In less time than a minute after Captain Whipple's answer, the boats were alongside of the Gaspée, and boarded without opposition. The men on deck retreated below as Duddingston entered the cabin.As it was discovered that he was wounded, John Mawney, who had for two or three years been studying physic and surgery, was ordered to go into the cabin and dress Duddingston's wound, and I was directed to assist him. On examination, it was found the ball took effect about five inches directly below the navel. Duddingston called for Mr. Dickinson to produce bandages and other necessaries for the dressing of the wound, and when finished, orders were given to the schooner's company to collect their clothing and every thing belonging to them, and put them into their boats, as all of them were to be sent on shore. All were soon collected and put on board of the boats, including one of our boats.

They departed and landed Duddingston at the old still-house wharf, at Pawtuxet, and put the chief into the house of Joseph Rhodes. Soon after, all the party were ordered to depart, leaving one boat for the leaders of the expedition, who soon set the vessel on fire, which consumed her to the water's edge.

The names of the most conspicuous actors are as follows, viz.:— Mr. John Brown, Captain Abraham Whipple, John B. Hopkins, Benjamin Dunn, and five others, whose names I have forgotten, and John Mawney, Benjamin Page, Joseph Bucklin, and Turpin Smith, my youthful companions; all of whom are dead—I believe every man of the party, excepting myself; and my age is eighty-six years this twenty-ninth day of August, eighteen hundred and thirty-nine.—1839.

Ephraim Bowen

After the burning of the Gaspée, John Brown and several others of the expedition were in danger of being taken prisoners for the crown government or English naval authorities at Newport had offered substantial rewards for the capture or identification of persons connected with the affair, so it is said that John Brown for a while never slept more than a night or two in any one place but kept moving about. In his case this was easy to do for, besides his city residence, he had country seats in Cranston, Gloucester, Rhode Island, north Providence, Point Pleasant in Bristol, and the Spring Green estate in Warwick. However, Captain Abraham Whipple, who was afterward a commodore in the Continental Navy, commanded the flotilla of rowing boats at the burning of the Gaspée and seems to have been known to the English naval forces at Newport, commanded by Sir James Wallace, for they had written communications with each other which have been preserved. As the language used by both sides is so typical of that used in the seventeen seventies I quote it here:

Wallace to Whipple.

You, Abraham Whipple, on the 10th of June, 1772, burned his Majesty's vessel, the Gaspée, and I will hang you at the yard arm.

James WallaceWhipple to Wallace:

To Sir James Wallace

Sir, Always catch a man before you hang him.

Abraham Whipple

Perhaps John Brown and his brother, Moses Brown, are best known as early educators in America. Their first attempt to introduce free schools in Providence was made in 1767. The Brown brothers were influential, particularly financially, in removing the College of Rhode Island from Warren to Providence where it was renamed Brown University. John Brown was one of the largest contributors to the institution of which he was the treasurer for twenty years. On May 14, 1770 he laid the corner stone of its first building now known as University Hall, which was erected on the original home lot of his ancestor, Chad Brown.

Before 1787 John Brown's city residence was at 37 South Main Street (later torn down for the erection of the Mechanics Bank) and here he gave his famous dinner to General Nathanael Greene, which was said to have been the largest dinner ever given in Rhode Island. In 1787 he built his Power Street mansion, at that time the finest house in the city. It was designed by his brother, Joseph Brown, who, besides being a professor of Experimental Philosophy at Brown University was a talented architect and, I believe, designed the First Baptist Church of that city and some of the buildings of Brown University as well as other Providence residences. He is the great uncle of Captain Nat, I believe, who, before 1800, first tried outside ballast on a sailboat.

Moses Brown, the youngest of the brothers, was a Quaker and, although he joined with his brother, John, in most enterprises, he kept aloof from the Revolutionary struggle. Moses was a successful business man and banker. Among other things, he financed and encouraged Samuel Slater, an English mechanic, to employ his skill in working out the first water-driven frames in America. Up to this time no spinning machinery had been successfully driven by water power. All obstacles were at length overcome and the great industry of spinning cotton by water power was inaugurated. Moses Brown lived to be ninety-eight years old and became quite wealthy, but his principal interests were charitable and educational. Among other things, he started the Friends' New England Boarding School, now called the Moses Brown School. An engraving of him was included in a brochure of early American educators among whom were Franklin, Ritten-house, and others.

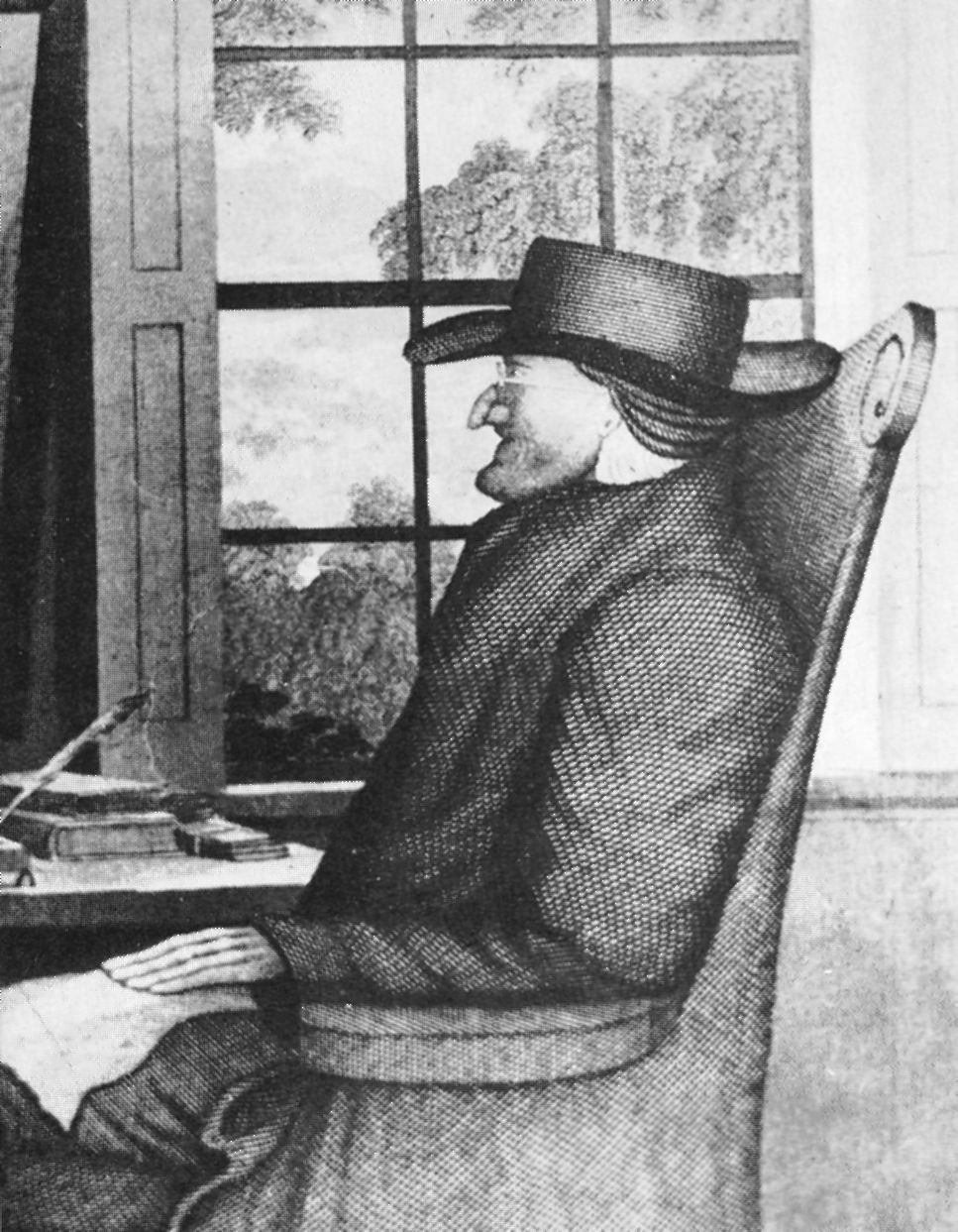

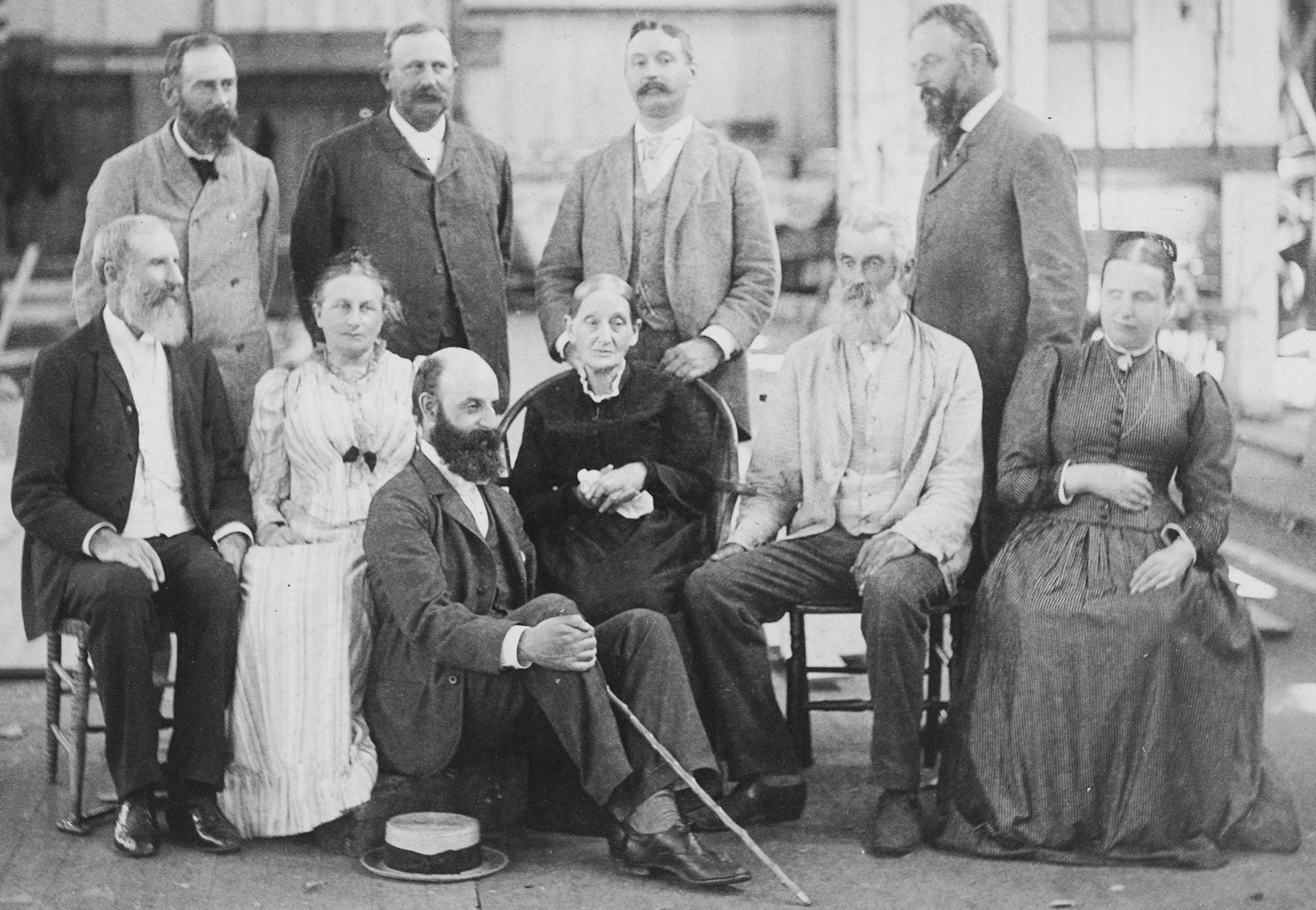

After this slight review of the Brown family which brings us down to Sarah Brown, the daughter of John Brown who married Carl Frederick Herreshoff and was of the sixth generation of Browns in America, we get back again to the Herreshoffs. Carl Frederick, as we have said before, died in 1819 leaving Sarah on the Point Pleasant Farm at Bristol with five children, all of whom had been born in Providence between 1802 and 1809. Both she and her children spent the rest of their lives either on the Point Pleasant Farm at Bristol or in visiting relations in Providence. John Brown had given this daughter the best education available at the time and she was especially proficient in music and mathematics, deriving consolation and giving pleasure to others by her skill on the piano which she played in a remarkably correct and brilliant manner. Her knowledge of astronomy also afforded her pleasure during many periods of quiet life spent in the country during the long years of her widowhood. She was delicate in constitution, austere in presence, and exact and methodical in her daily vocations. She read much and led a life of ease, indulging in her love of music and literature to her last days. Sally Brown Herreshoff must have inherited some fortune from her father, for both she and her children led the life of country ladies and gentlemen for almost two generations. She also inherited from her father a quantity of very fine furniture, china, silver, and portraits. There is no doubt that Captain Nat inherited some of his strong characteristics from this remarkable woman, his grandmother, but I must add that Sally Herreshoff was reputed to have been somewhat of a shrew and was quarrelsome. One of Captain Nat's brothers always said the later Herreshoffs inherited their love of rowing with one another from Sally Brown. She finally died at Bristol in 1846 in her seventy-third year.

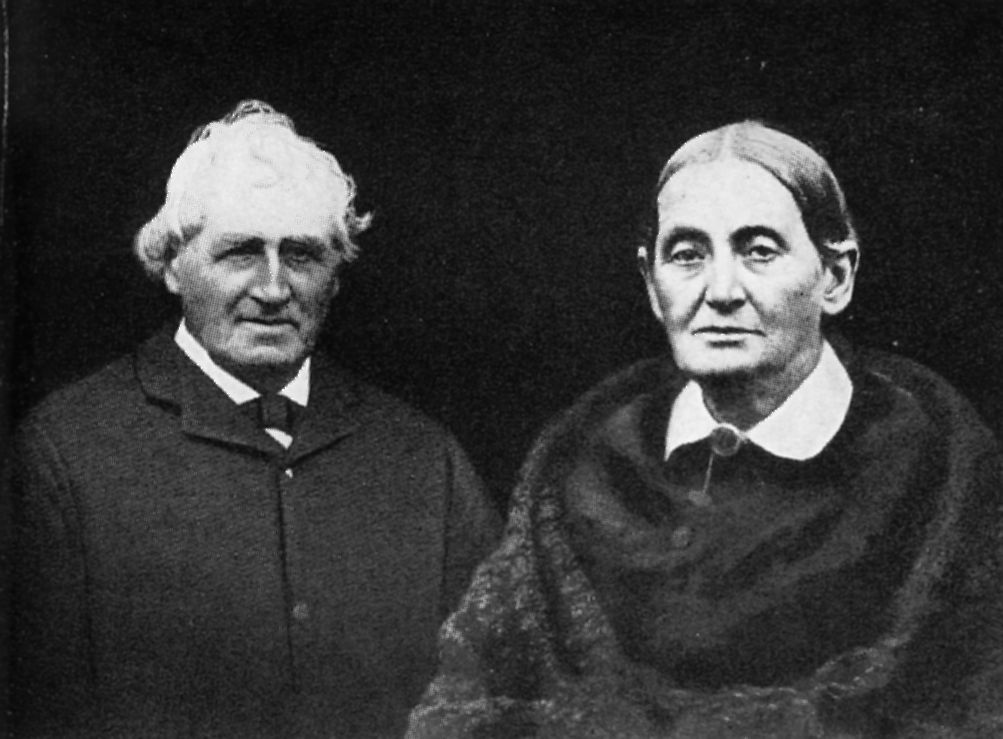

Only one of the children of Sally Brown and Charles Frederick married; this child was also named Charles Frederick Herreshoff and was born in Providence in 1809. He graduated from Brown University in 1828 and afterwards lived on the Point Pleasant Farm with his brother and sisters. He seemed to have tried to run the farm as a gentleman farmer though all the time his thoughts were mostly on the water, for on one side of the farm was Bristol Harbor and on the other side Narragansett Bay. He was particularly interested in mechanics and was a skillful and finished woodworker. He delighted in making swinging gates for the farm, frames for harrows, and occasionally built a small boat just for amusement. But there was a young lady named Julia Ann Lewis from Boston who visited Bristol in the summers, coming over the road with her harpsichord by horse, wagon, and carriage, and this Charles Frederick, like his father before him, seems to have won his wife through a common interest in music, for Charles Frederick married Julia Ann Lewis on May 15, 1833. Julia Ann was descended from the famous Massachusetts families of Winslow and Lewis who, I believe, have two or more Mayflower antecedents. Her father was Joseph Warren Lewis of Boston, a captain of packet ships running between England and Boston who made eighty voyages over the ocean in that capacity and later became a Boston merchant. Lewis Wharf in Boston is named for the family.

In her youth Julia Ann lived on Charles Street, then (about 1820) a stylish outskirt of the city of Boston, which looked out over the Charles River only a short distance west of the State House. Just before this time Boston had produced some remarkable painters and was shortly to produce a string of talented literary men. At that time Boston could truthfully be called the hub of education and Julia Ann seems to have taken full advantage of the opportunities thus available for in later years she was able to teach her children in almost all subjects. She had been abroad with her father, and one of the things long cherished in the family was a fine French clock her father had purchased for her when in Europe.

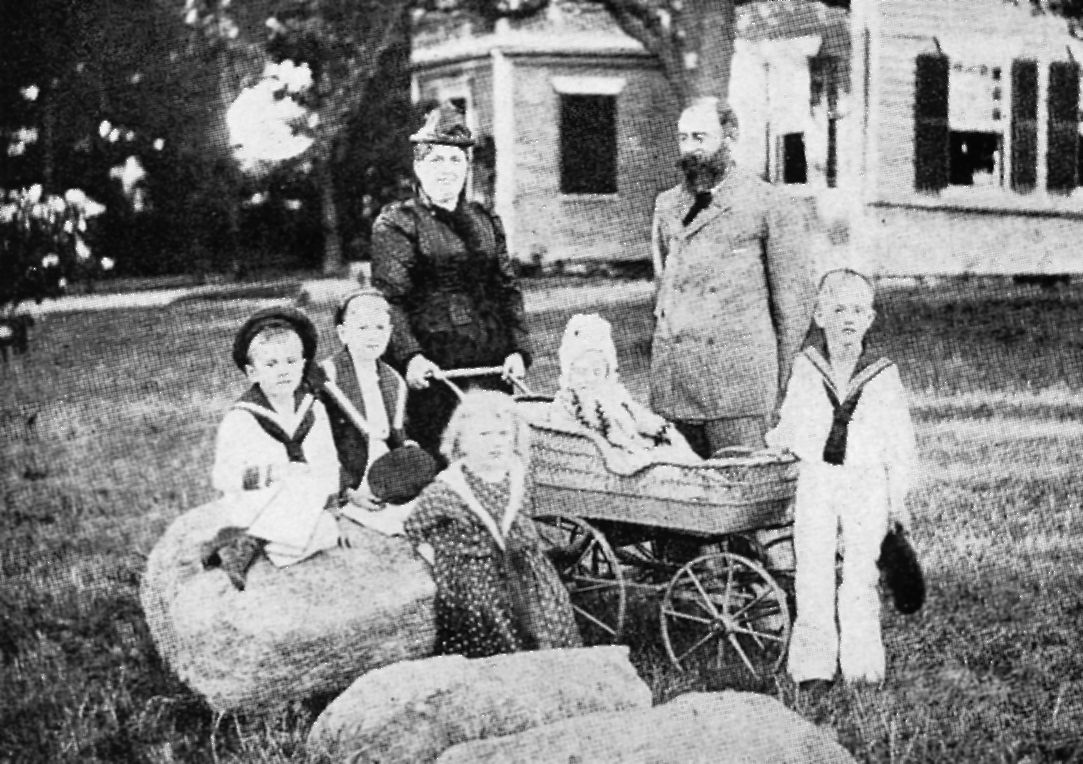

Charles Frederick and Julia Ann had nine children, all born on the Point Pleasant Farm at Bristol between 1834 and 1854, all of whom lived to a ripe old age, which certainly was a remarkable feat in those days of high child mortality. So Julia Ann must have been a wonderful mother. Our subject, Captain Nat, was the seventh child and the fifth son and I will now quote almost verbatim from some writing of Captain Nat describing his early life on the Point Pleasant Farm in about 1855.

The house had a great kitchen with its brick oven of very ample proportions which was fired up every Saturday to do the week's baking of pies and cakes. In my younger days there was a stove with rotary top, a big affair in which there were six or eight holes for kettles, and by revolving the top any one or two of the kettles could be brought over the fire, the gasses passed under the others. This stove was replaced in about 1855 by one similar to the hard coal stove of later days.

Next to the kitchen and on the other side of the great chimney was the dining room which was also our living room. This had a very large fireplace kept burning and I remember very well the baking of johnny cakes on the hearth. The Indian meal and water dough was plastered on a board and propped up close in front of a hot fire, in a quite similar manner to the way the Indians did their cooking.

Our dining room had a long black walnut table which was necessary as there were nine children of us besides our parents and usually an aunt or uncle. The room also had my mother's Chickering piano, her work table, book shelves, and a beautiful French clock that was on a shelf in the corner. Of course there were many chairs and some of them very fine old mahogany which had belonged to greatgrandfather John Brown.

In winter, after Christmas, a "fire-board" was placed in the throat of the fireplace and a coal burning stove was set just outside the hearth. This stove was a vertical sheet iron cylinder with fire brick lining at grate; the usual doors for fire box and ash pit. Just back of the stove my father had arranged a sheet iron drum of about the same size as the stove into which the flue ran. This drum had a baffle plate inside to compel the hot gasses to heat it all over; a pipe from this drum went up into the chamber above and into another drum, then to the chimney flue. With these drum heaters the heating of the living room and chamber was most efficient.

In those days my sleeping quarters were with my next younger brother in a "trundle bed" which when not in use rolled in under the parents' bed. It was mounted in wooden wheels four or five inches in diameter set in slots in the short legs of the bed. I well remember the fun we had after awakening mornings in putting our legs under the bed as far as our little bent up legs would allow, then giving a great push trying to reach the other side of the room.

I can very well remember the first mowing machine father had, and the trial of it, and think it was in 1855. Before that all mowing was done by scythes, and extra men were hired for it. Hay rakes were in use before that time, also cultivators and harrows, and I remember Father making the wooden part of some of these farm tools, also some very nice swinging gates to be put in driveways about the farm, for he was very fond of carpenter work and of doing it well. He had also built several very nice small boats—just for the fun of it.

In 1856 the Point Pleasant Farm was given over to Charles Frederick's elder brother, John Brown Herreshoff, so Charles Frederick and his family moved across the harbor to the town of Bristol and took a house at the lower end of the town, overlooking the harbor. Evidently the old homestead on the Point Pleasant Farm was no longer large enough for Charles Frederick and his large family besides his brothers and sisters who often spent some of the year there.

No doubt some of my readers will say about now: Well, when are you going to tell about the sailboats?

To which I will reply: Very soon now, but many people nowadays enjoy hearing about New England life in former times and it has been necessary to describe Captain Nat's principal ancestors to give one an idea of his inherited characteristics.

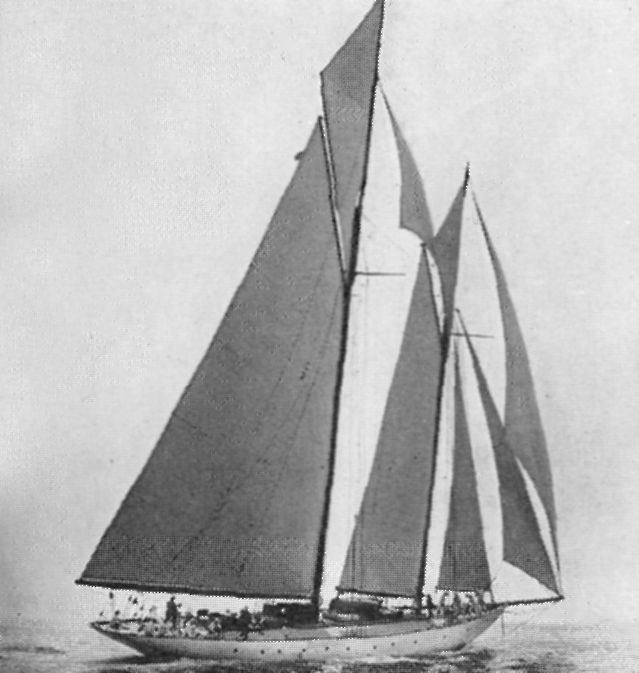

At the time the family moved over to the town side Charles Frederick was forty-seven years old and he must have inherited some means from his mother for I do not think he had any regular employment after the move to Bristol. This allowed him leisure for his principal pleasure, which was sailing, and I understand he visited every cove and island in Narragansett Bay annually and knew the exact location of many rocks.

Charles Frederick had built and owned sailboats while still living on the Point Pleasant Farm and one of them was the first Julia. She was probably built about 1833, was about twenty-three feet long, and was quite similar in model and rig to other boats of the bay at that time and even before. This first Julia was a roomy boat with large cockpit, and besides taking many of the family sailing all over the bay, she was used to take the family visiting at other country estates around the bay where friends and relations lived. One of the places she visited often was Greensdale, the estate of General Nathanael Greene about half way down the island of Rhode Island, and perhaps six miles by water from Bristol. General Greene had been next in command to Washington in the Revolution and was a friend of Charles Frederick's grandfather, John Brown, so the families had been very intimate. In those days Greensdale was occupied by a son of the general, Dr. Nathanael Greene, who was a particular life-long friend of Charles Frederick's, and that is the reason our subject was named Nathanael Greene Herreshoff. At any rate these visits to Greensdale were a particular delight to young Nat for apparently Mr. Greene made a great deal of his namesake.

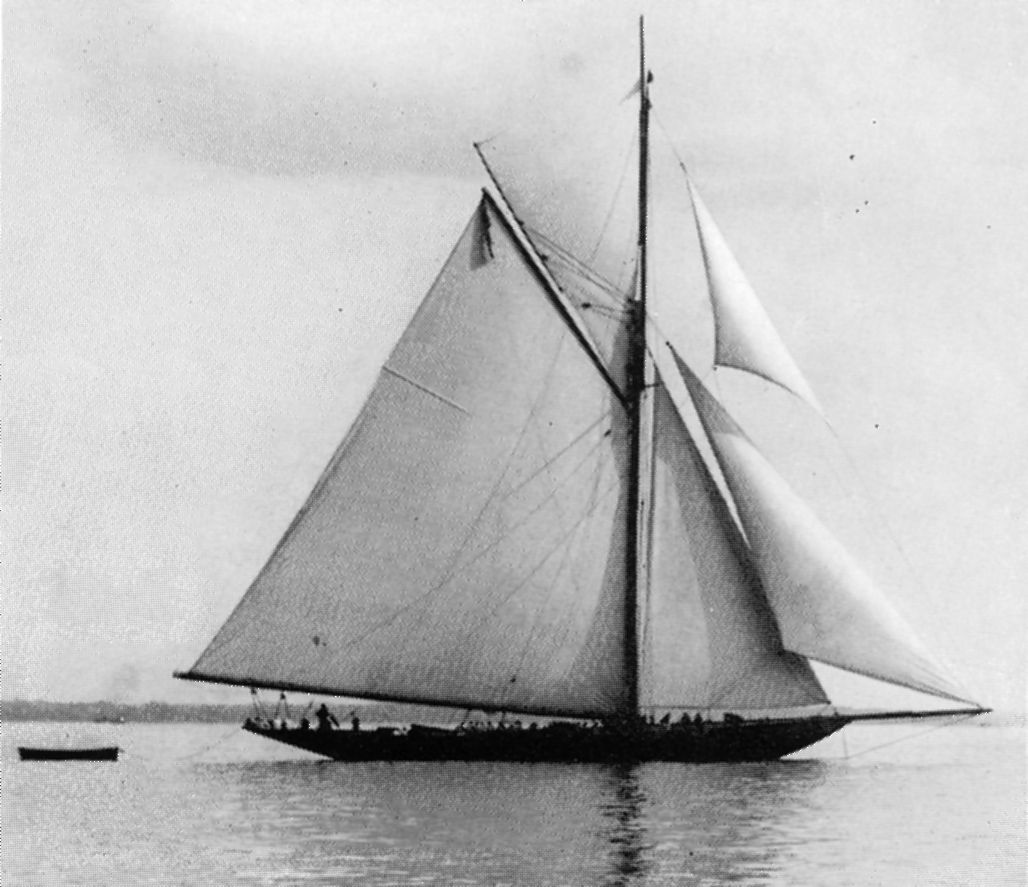

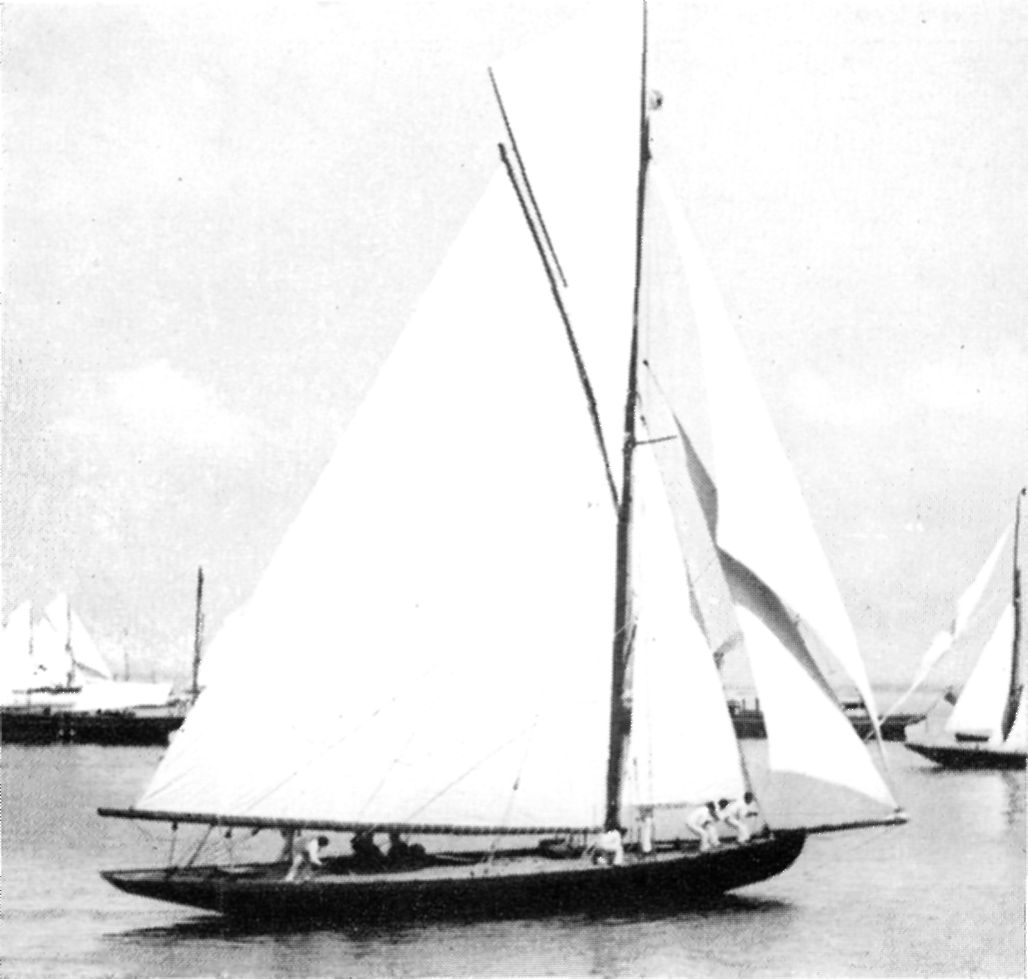

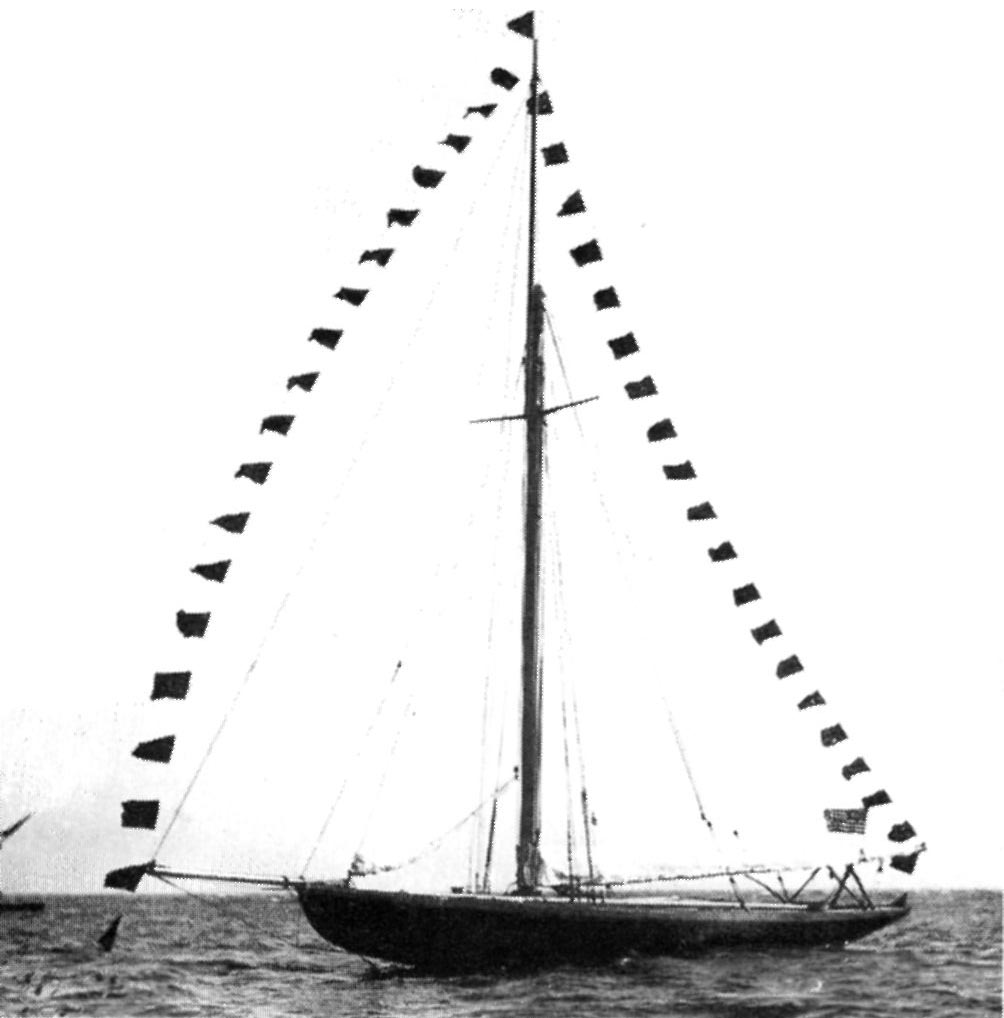

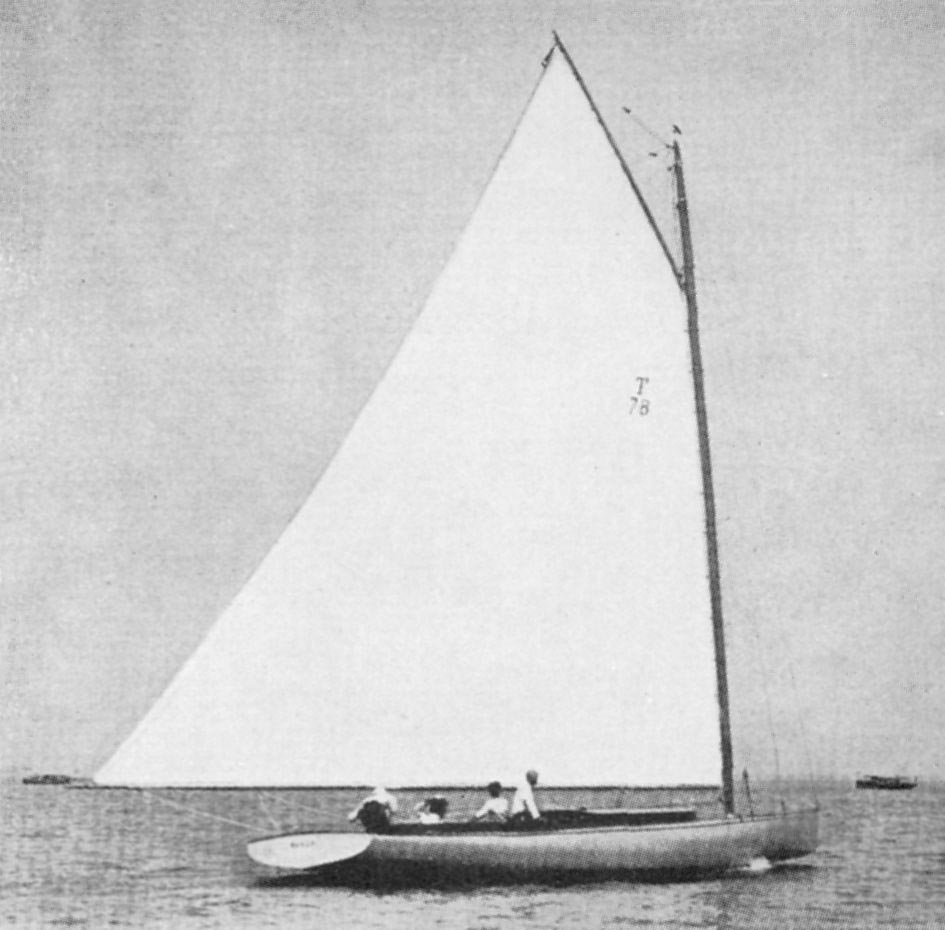

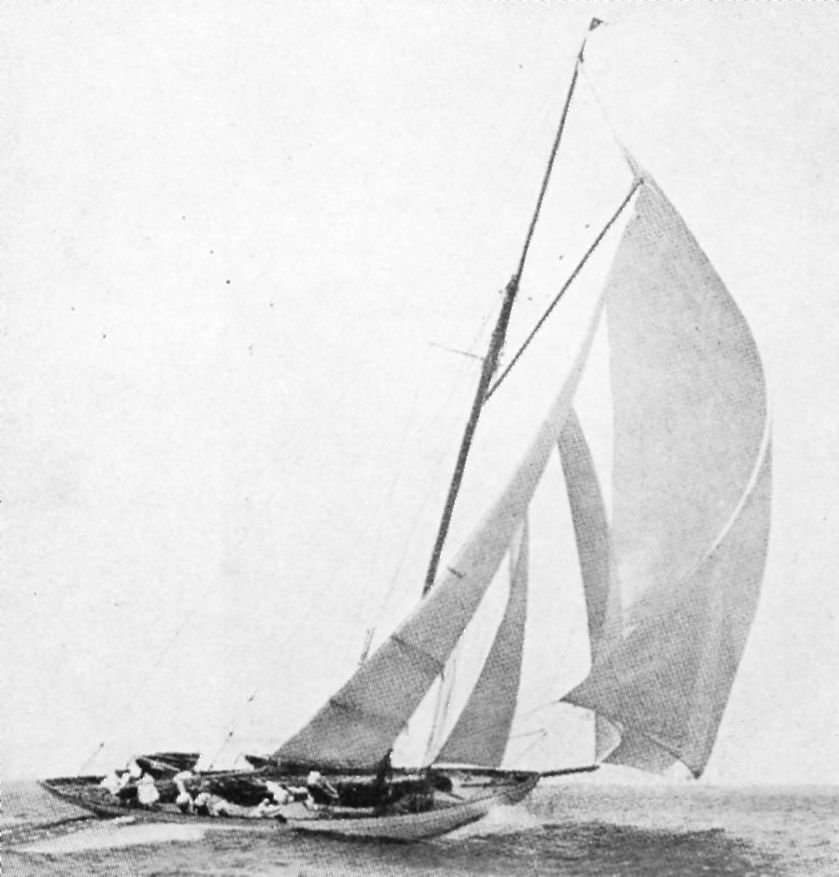

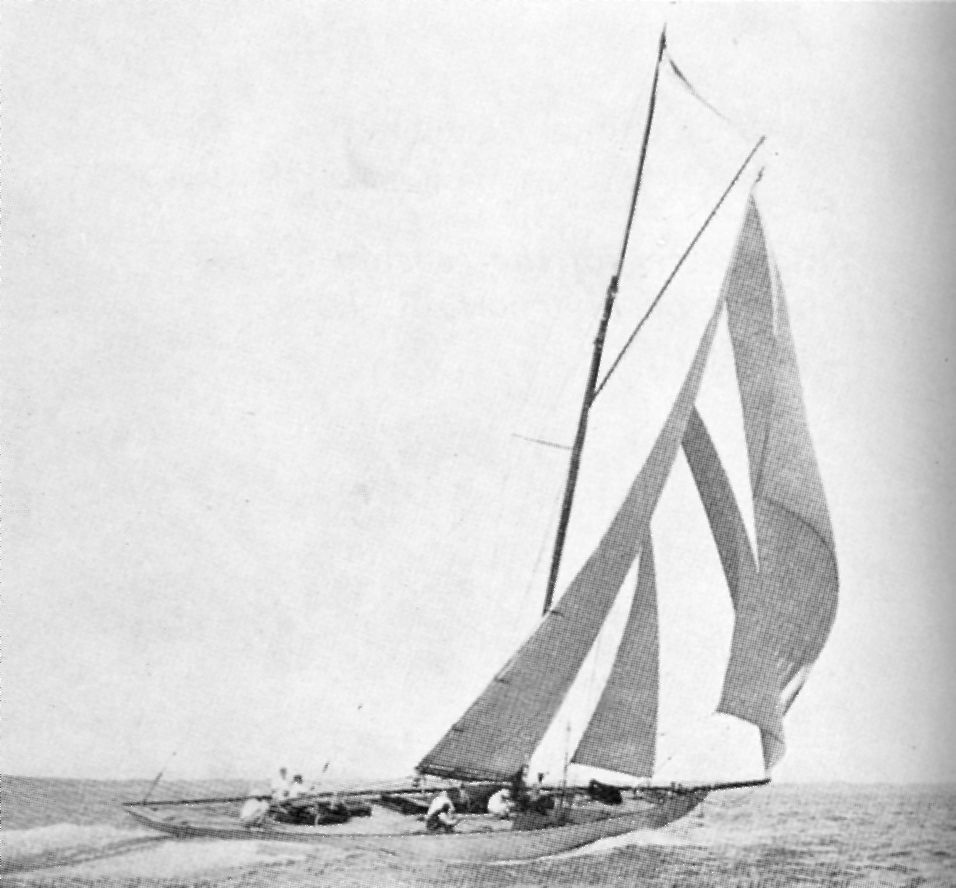

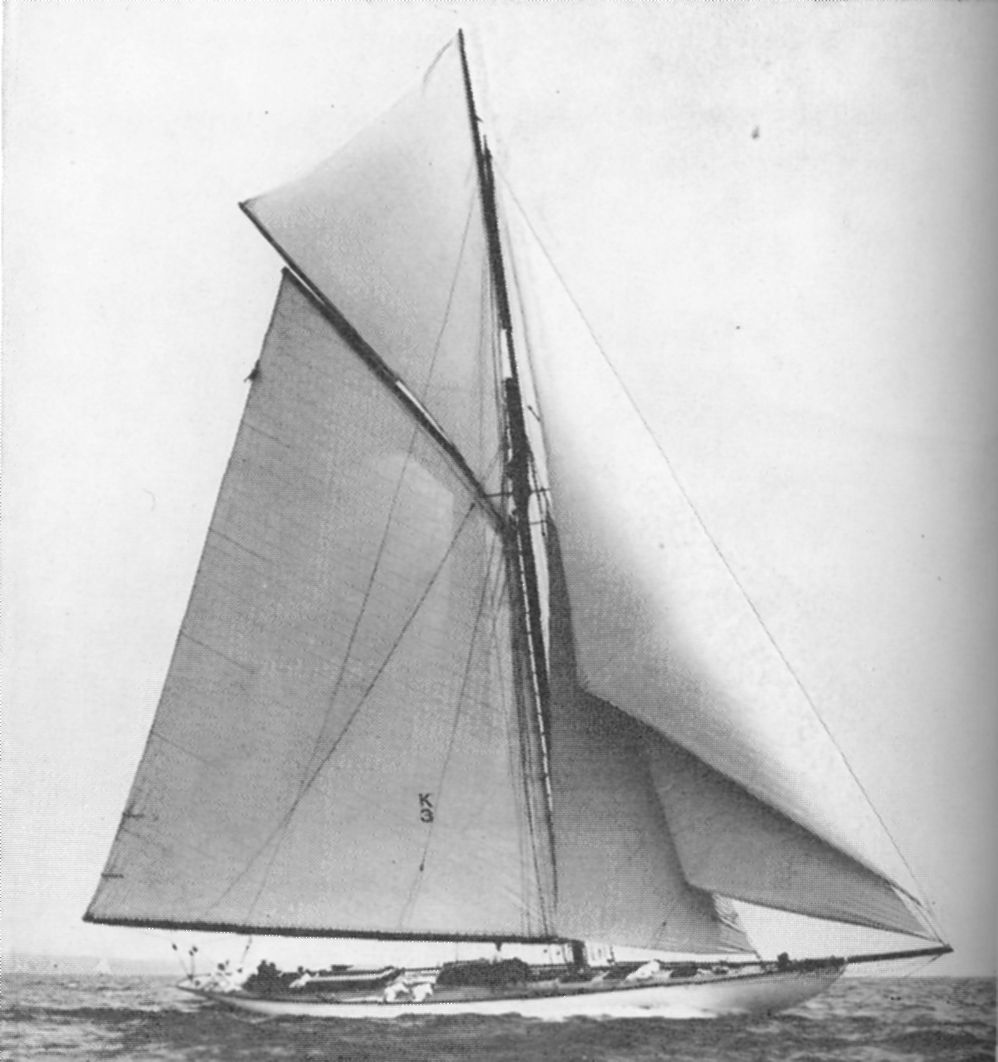

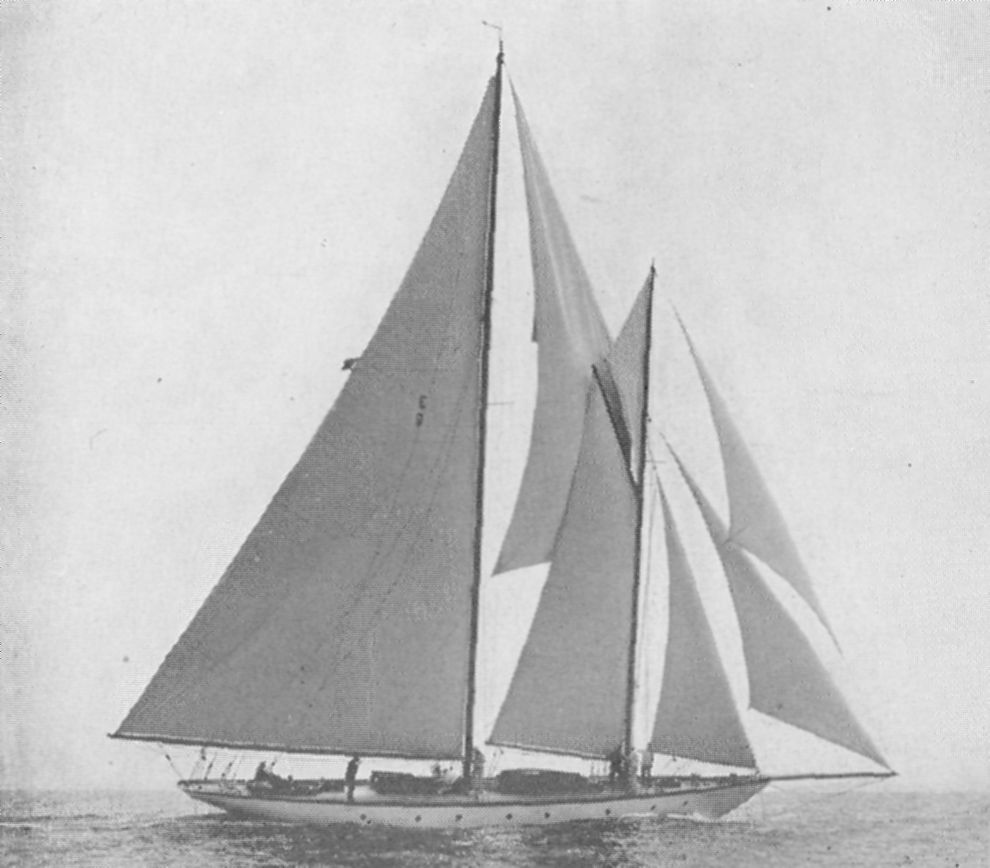

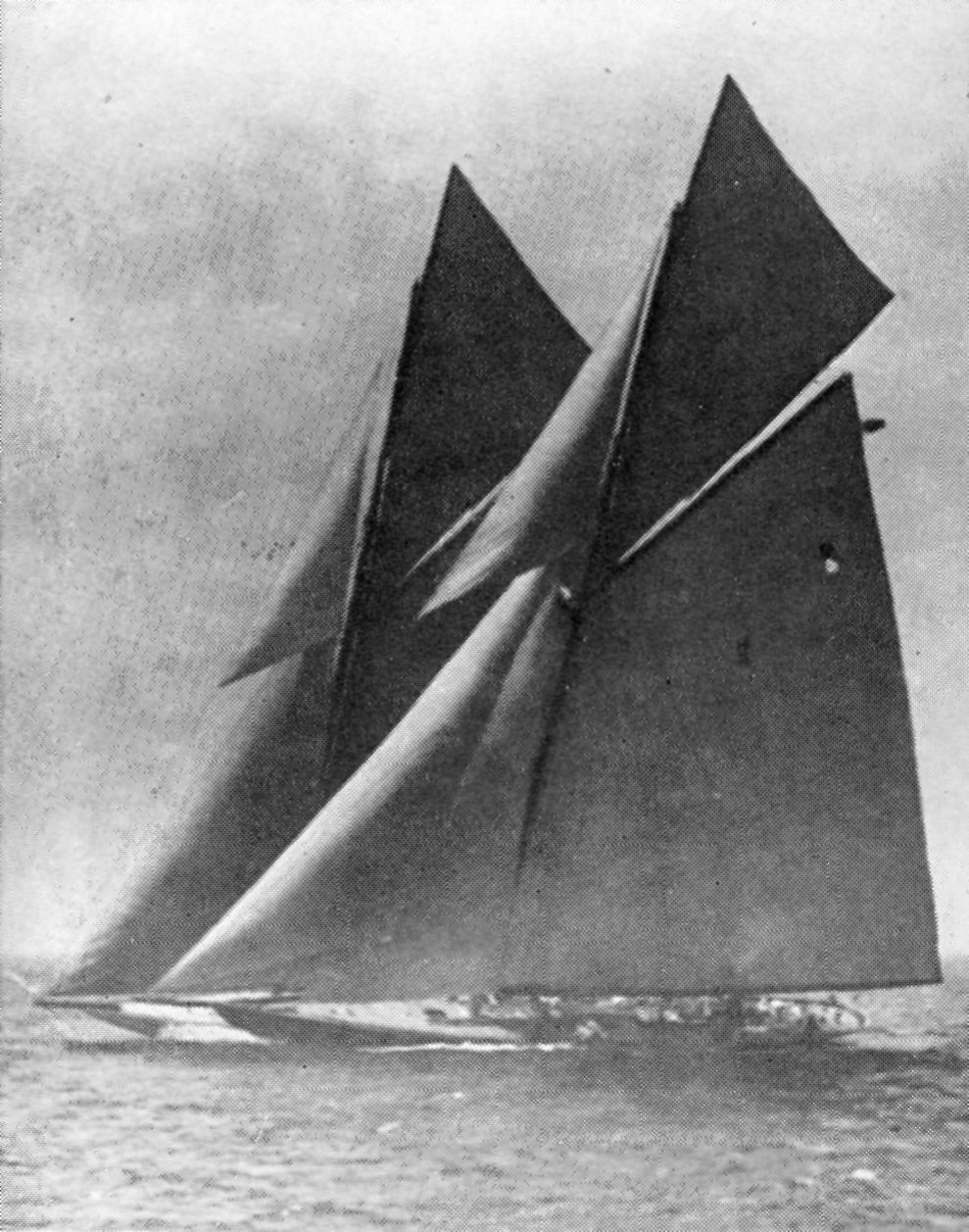

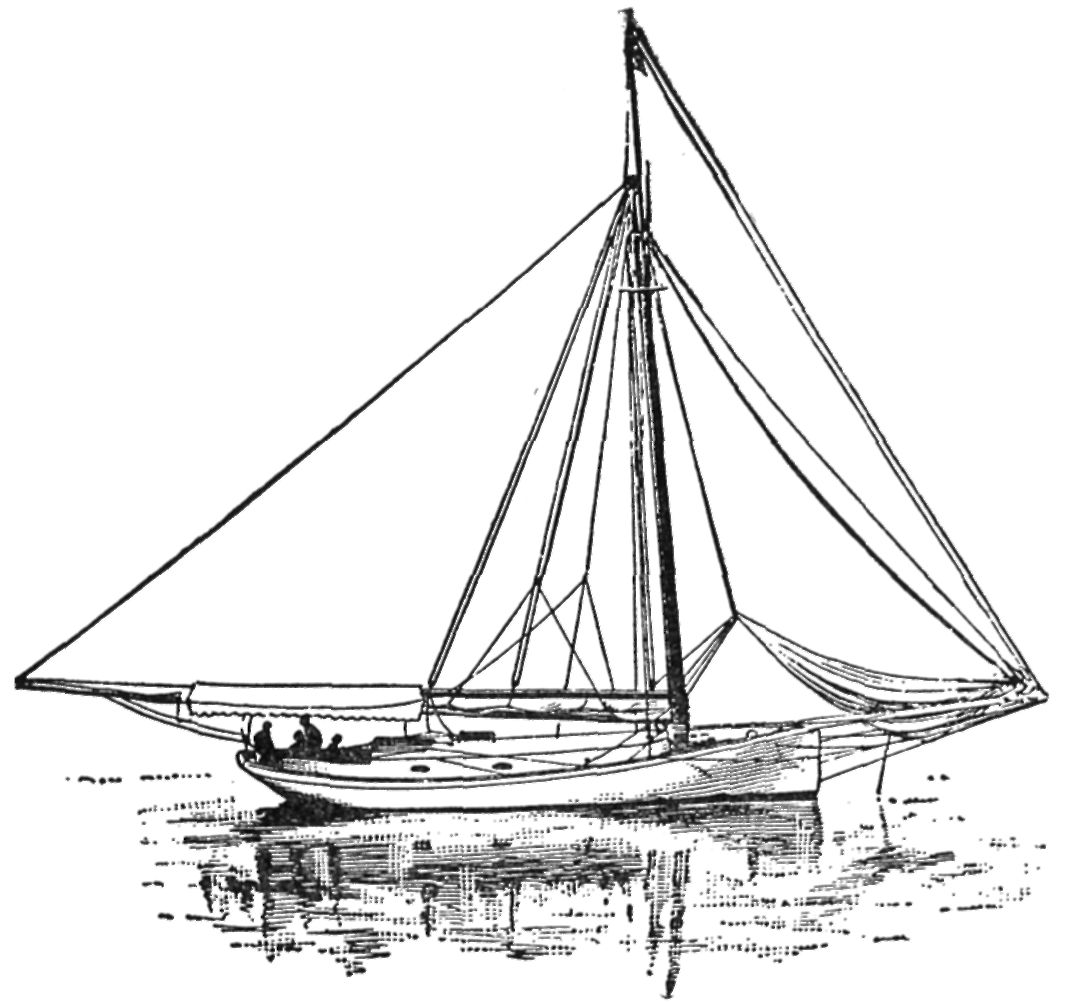

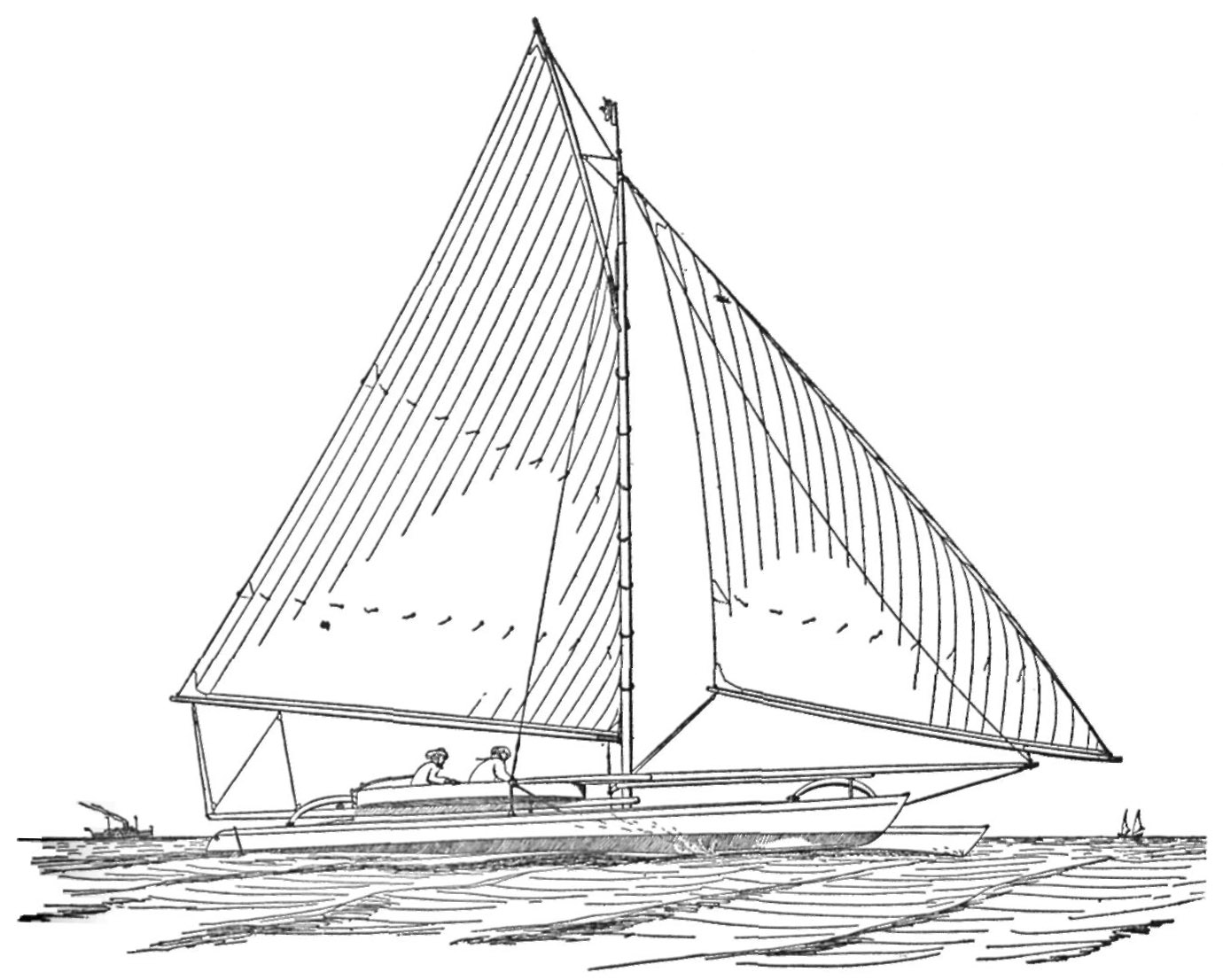

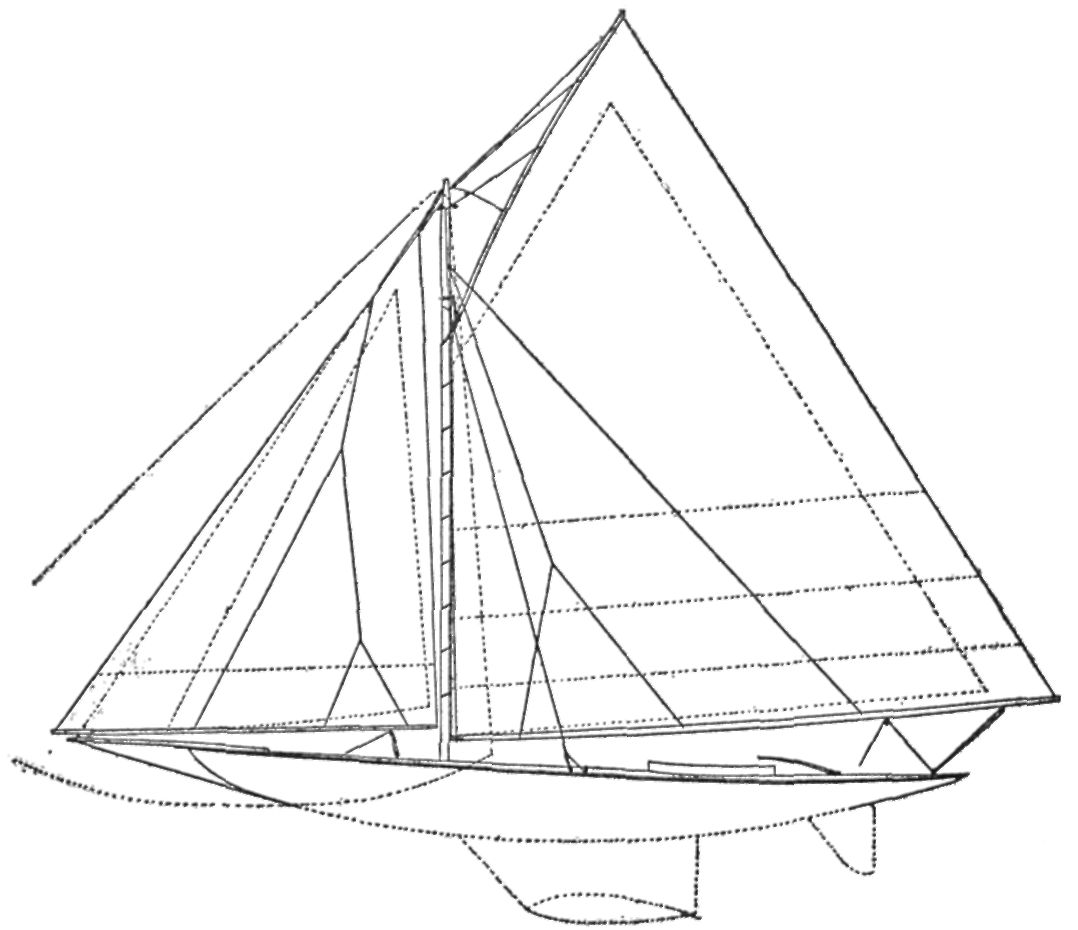

Racing small sailboats had been popular in Narragansett Bay since Colonial times, and the general type of craft used was developed at Newport. It was a single-masted craft with the rudder hung on the stern and was heavily ballasted with cobble stones. These boats were called Point boats for they were mostly built on a point of land extending out into Newport Harbor where there was a colony of small boatbuilders. This type of boat was later called a catboat when it became popular around New York, and after one named Una was taken to England all Europe spoke of them as Una boats for the next hundred years. Some of these early Narragansett Bay boats were owned and sailed by retired sea captains. No doubt some of them had been captains of slavers and privateers and were great characters.

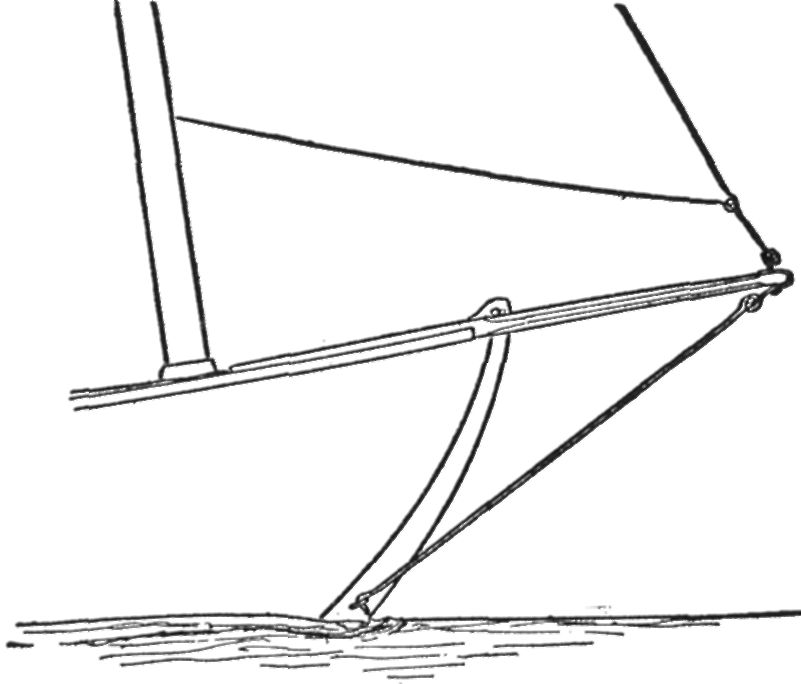

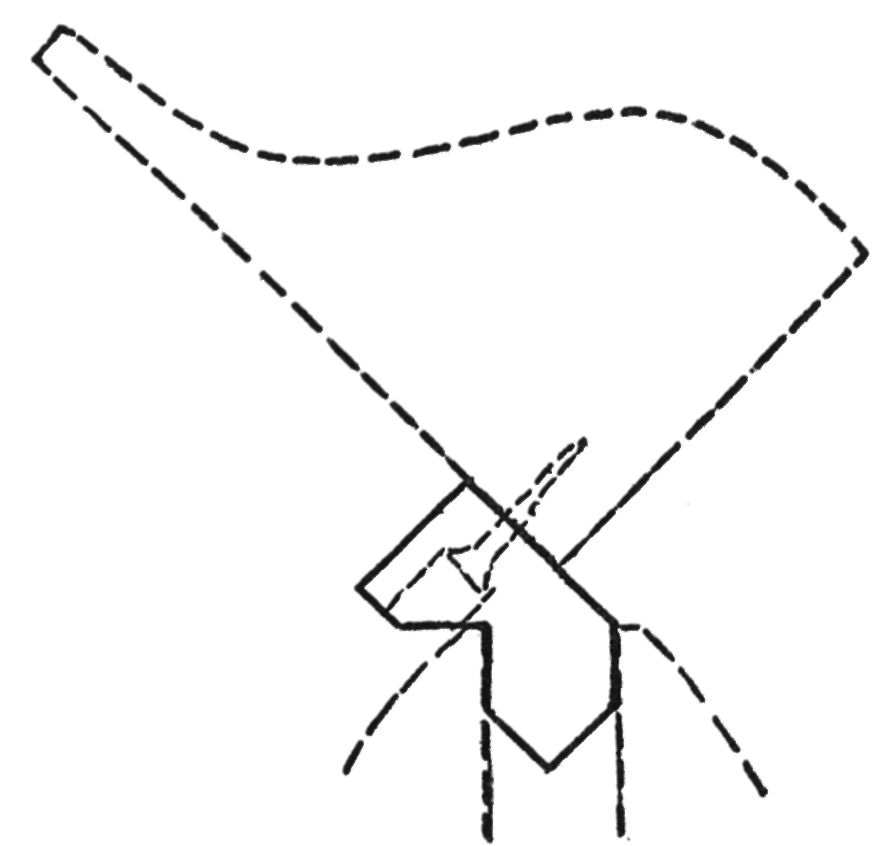

By 1850 Bristol, which is midway between Providence and Newport, became a favorite meeting ground for the boats from the several harbors in the bay. Bristol also had a most skillful sail maker named Jonathan Alger who owned and sailed one of these single-masted boats, so that altogether the men and boys of Bristol became very boat-minded. I must note that most of these small sailboats of Narragansett Bay had a removable bowsprit which fitted over the stemhead and was held down by a removable rod bobstay shaped like a long hook with the eye or link at the forward end of the bowsprit while the hook hooked into a staple driven into the side of the stem near the water line. These boats never carried a jib in racing but only in making long passages in light or medium weather. The whole bowsprit and its gear could be quickly removed and stowed below, the jib, of course, set flying.

By about 1855 Charles Frederick built Julia II for the keen racing in the bay, and after 1864, when she was fitted with a shifting ballast box running athwartships and carrying a weight of about five hundred and fifty pounds, seemed to have beaten all other boats of her size in the bay. My father, Captain Nat, in describing this gear says:

The ballast box was amidships in light weather but was always used when there was wind enough to heel the boat to any appreciable amount. In a freshening wind and wishing to get the box to windward, it was not hauled there, but by luffing up into the wind suddenly and releasing the trigger or ratchet at the right time the box would roll to windward from the momentum of the boat's turning when the helm was suddenly put up to bring her back on her course. It certainly made Julia pleasanter to sail and also safer and faster. Although this ballast box and similar ones were used in four different boats I do not recall any accident by its getting adrift.

In describing the care that was taken of these sailboats of Bristol in the eighteen fifties and sixties my father has written as follows:

In those days there was a great rivalry between the owners of boats in Bristol in keeping them in fine order and spick and span in every way. Before going aboard my father's boat, Julia (and all his boats were named Julia after my mother) each shoe or boot had to be examined to see if any nails were protruding from the bottom; if they were they had to come off, and the same happened if they had boot blacking on them that might come off onto the paint work. The sail was kept clean and white and held from ever touching the deck by lazyjacks. Only washed hands were used in furling it.

Any boat coming along side must be held clear and not touch Julia for fear of leaving a mark. Both air and water were clean in those days, and so all these particulars were possible. It may be unnecessary to add that the painting was done with the greatest of care and only after thorough sand papering till the surface was faultlessly smooth.

At each full and new moon Julia was laid ashore and the bottom scrubbed so as to keep her in racing condition and ready for an afternoon scrap with four or five other Bristol boats that were kept in the same condition. These boats were owned by retired sea captains and characters to be remembered.

Our subject, then called little Natty, was eight years old when the family moved over to the town, and although his mother had been teaching him before, he now started to regularly attend the Bristol public schools. He and his brothers soon found the rendezvous of several sea captains past their active days but fond of spinning yarns. Natty was an intent listener who was much impressed by these old seagoing characters and often recalled those scenes in his later life.

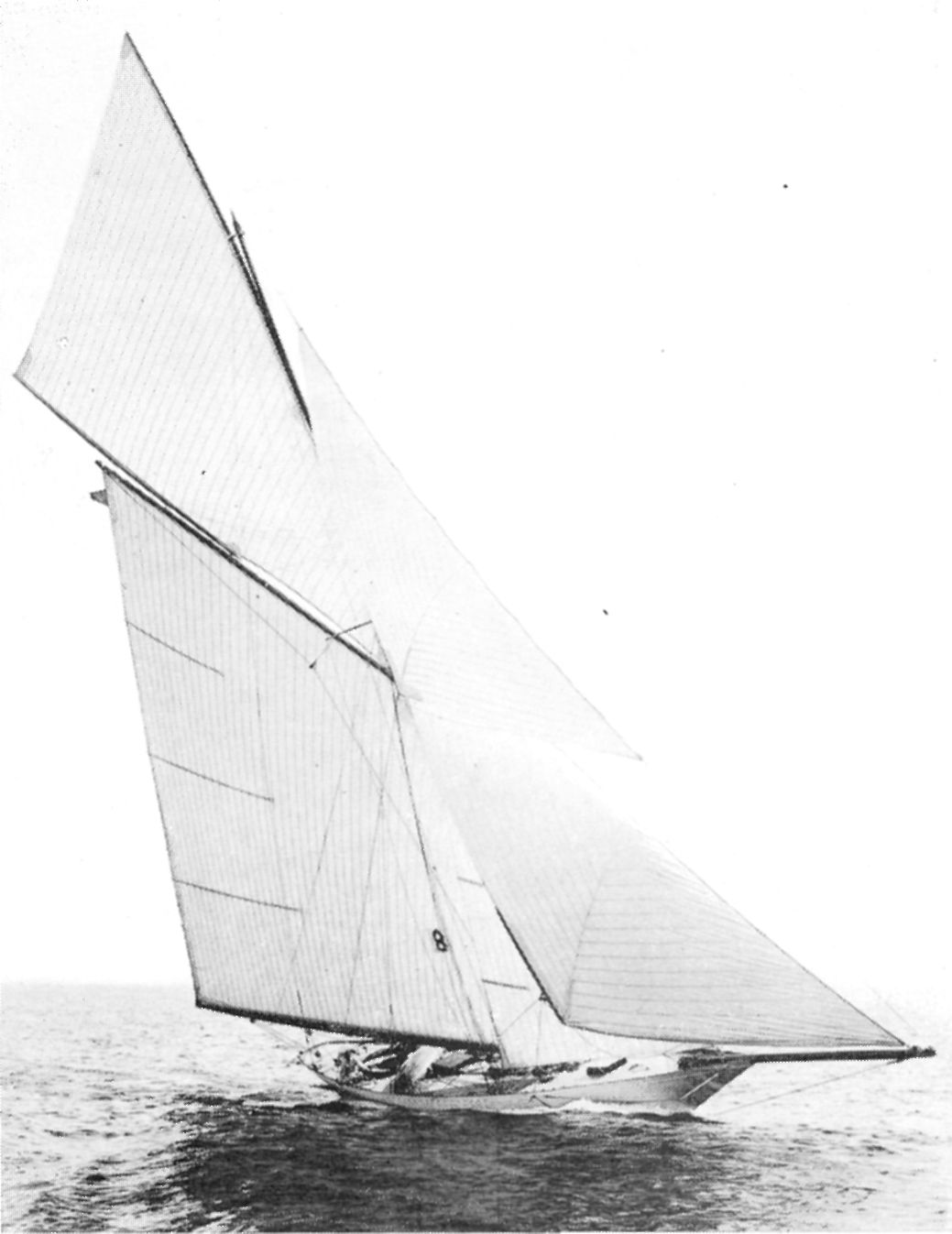

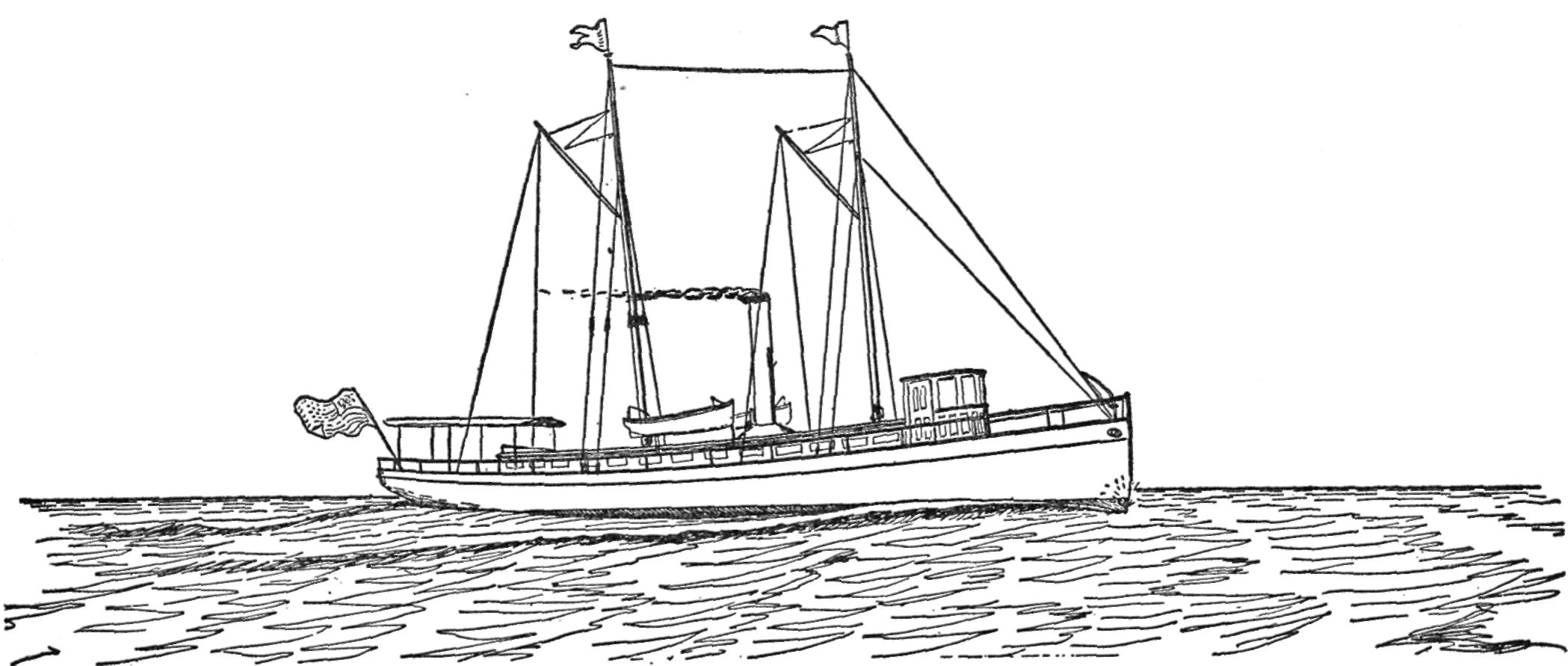

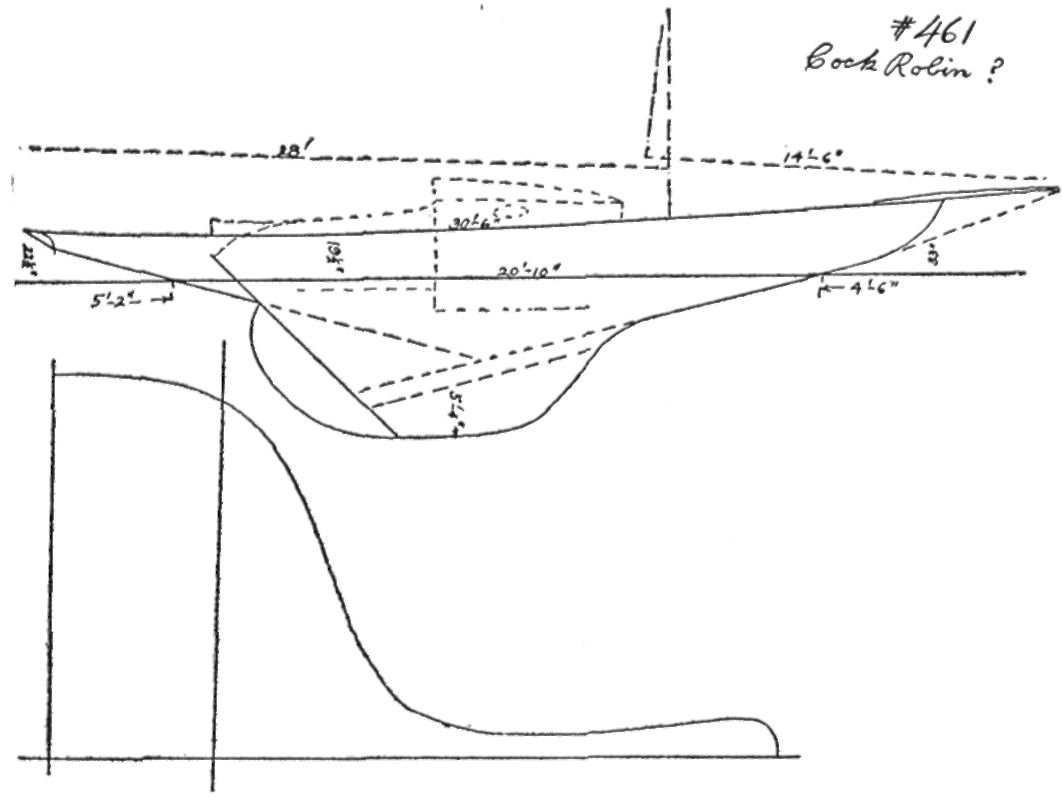

Even before the family left the farm, Nat's older brothers had started boatbuilding and the oldest brother, James, had developed into quite a mechanical genius. Another brother, John, who was seven years older than Nat, started his first boat named Meteor in 1855 when only fourteen, and as it happens that many people ask the author when John Brown Herreshoff started at boatbuilding, I will say again it was in 1855. Surely this small boat built by a boy may not be considered much of a beginning, but John Brown, whom we will afterward refer to as J. B. was continually at boatbuilding from that time until his death. Meteor was designed by J. B. and started by him while the family was living at the Point Pleasant Farm on Popasquash. She was what was called a skip-jack in those days and now called a V-bottom boat. She was twelve feet long and five feet wide; her bottom planking was laid crosswise; she had an enormous sail plan and was later used as both cat, and jib and mainsail. When Meteor was about half completed, J. B. lost his eyesight and this brings up the subject of blindness in that generation of the Herreshoff family. Four of C. F.'s children—three sons and a daughter—were stricken with blindness in their youth. They suffered with glaucoma. It is not hereditary or contagious but a serious condition characterized by increased interocular pressure which I believe can be controlled today. It is interesting that the other brothers and one sister had rather remarkably good sight, and you can imagine Captain Nat as a designer had to have good eyes. Yes, I will say more, Captain Nat not only had the best eye for lines or shapes of anyone I have ever known but he had remarkably keen eyesight when at sea. When in middle life he was inspecting his various boat shops—sail loft, machine shop, foundry, or pattern shop he could see at once almost the length of the shop if some piece of work was being done wrong.

Well, let us get back to the Meteor and J. B. When he first lost his sight J. B. was very despondent for a few months but his energy to do things soon returned and he, with the help of his father, finished Meteor in 1857. In spite of his blindness she was sailed and raced by J. B. with his younger brother, Nat, aged nine acting as his eyes. Meteor was sailed by the boys for three years, capsizing twice, but each time their father in Julia picked them up and righted Meteor.

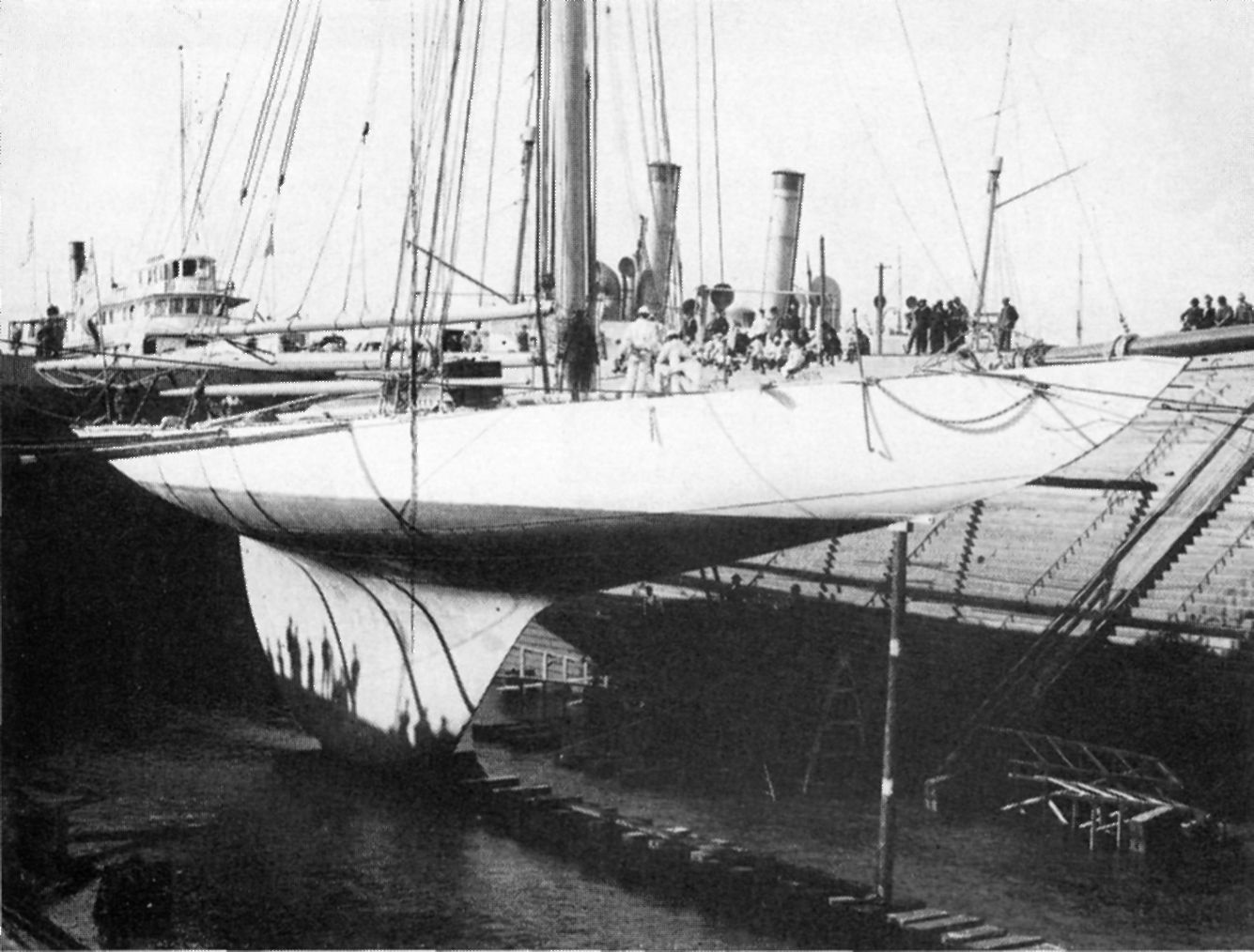

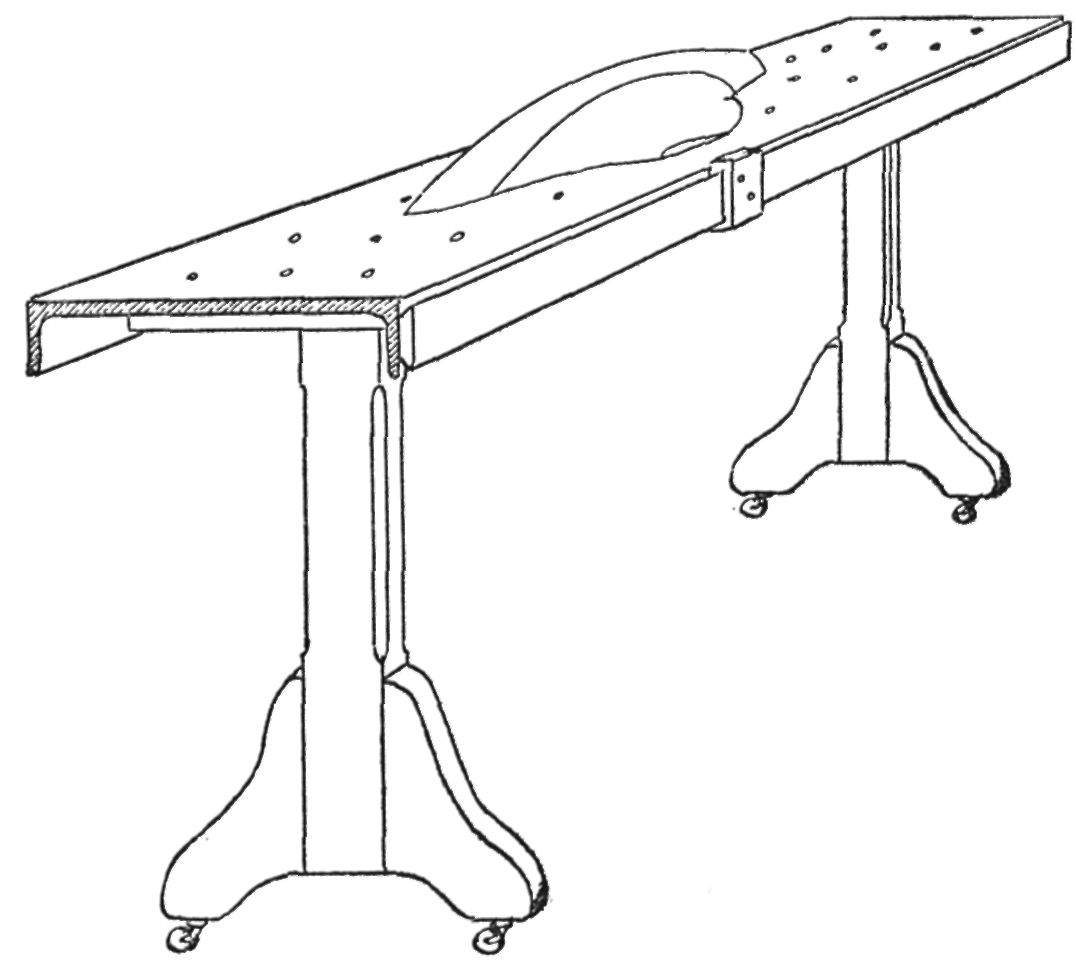

Almost in front of the house where the Herreshoffs lived at Bristol, and right on the water, was a building called the Tannery which previously had been used for dressing leather. C. F. either acquired this building or the use of it, for from 1859 onward all Herreshoff boats or yachts were built in this locality and other adjoining land acquired later.

The next sailboat the Herreshoffs built was Sprite, and I will give you some notes on her written by Captain Nat.

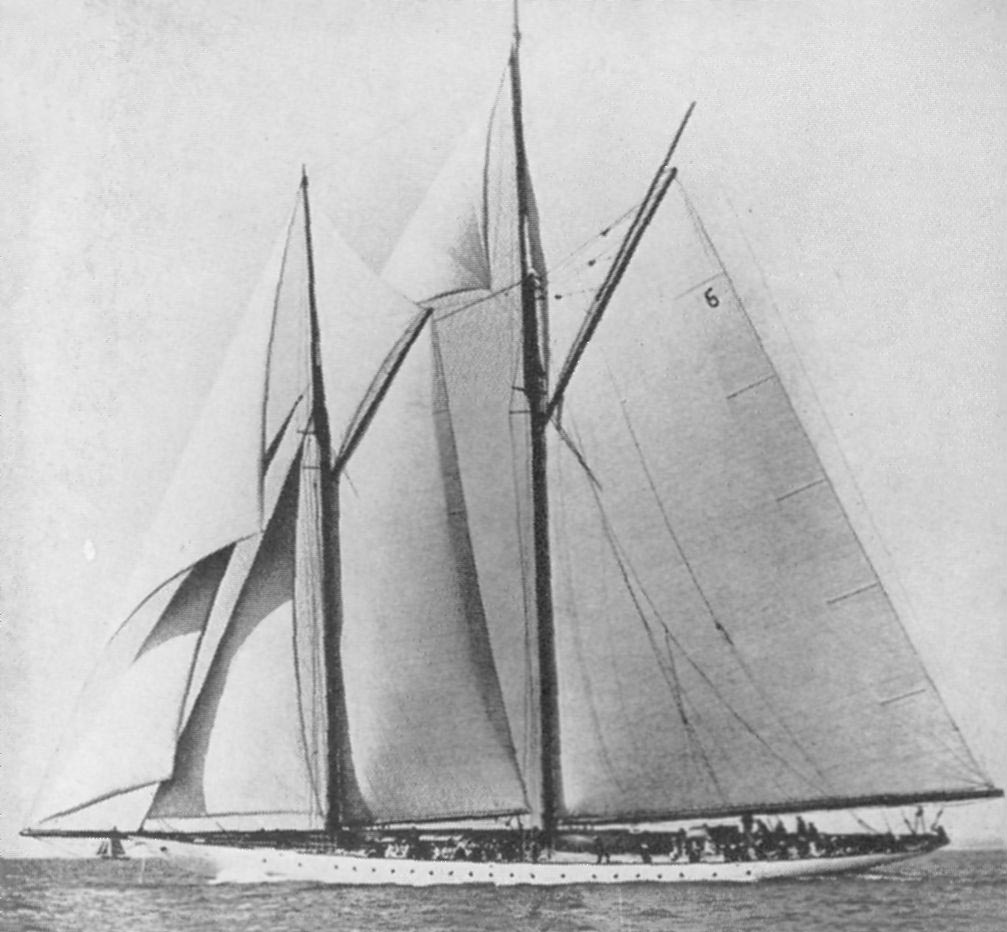

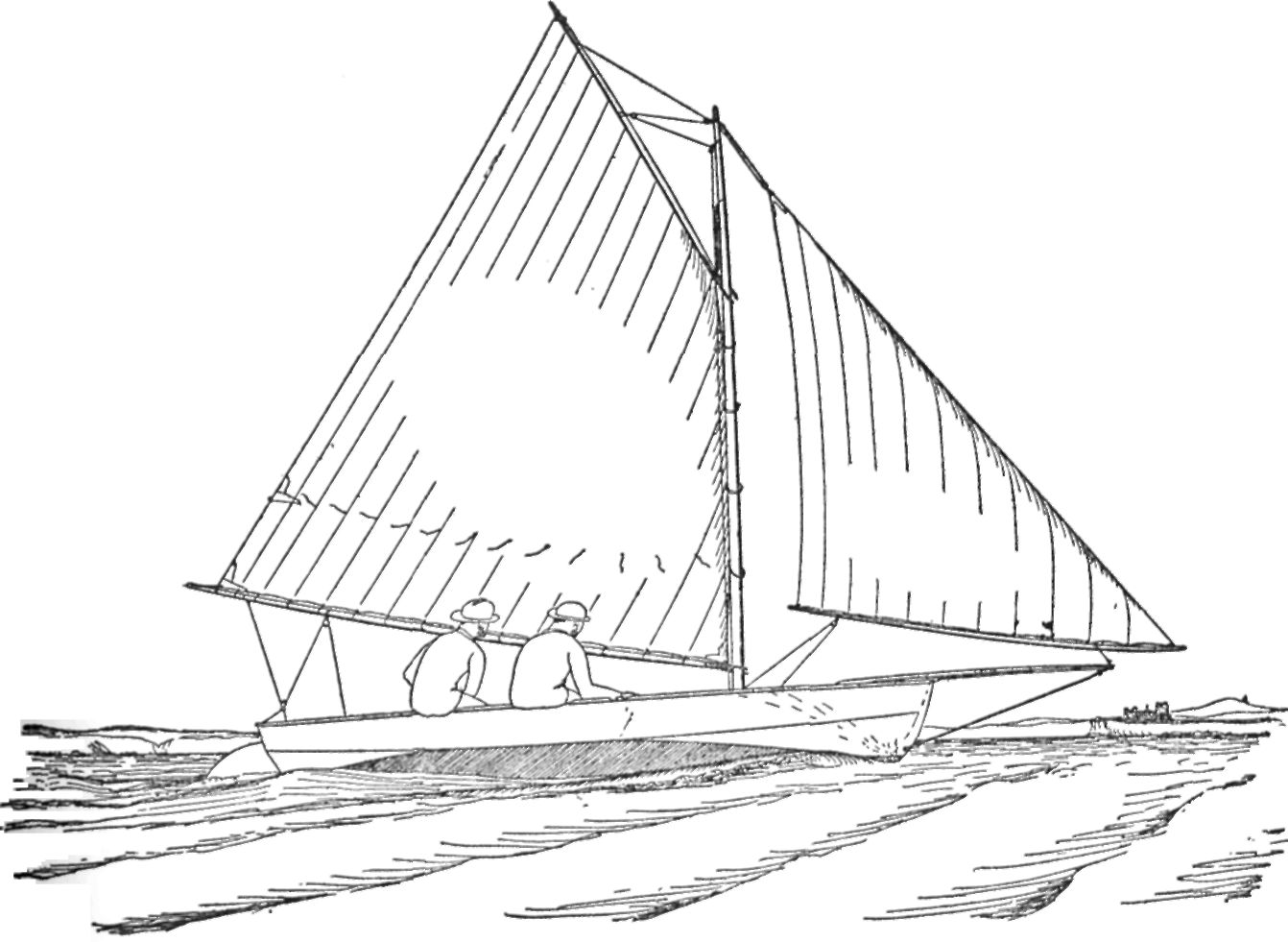

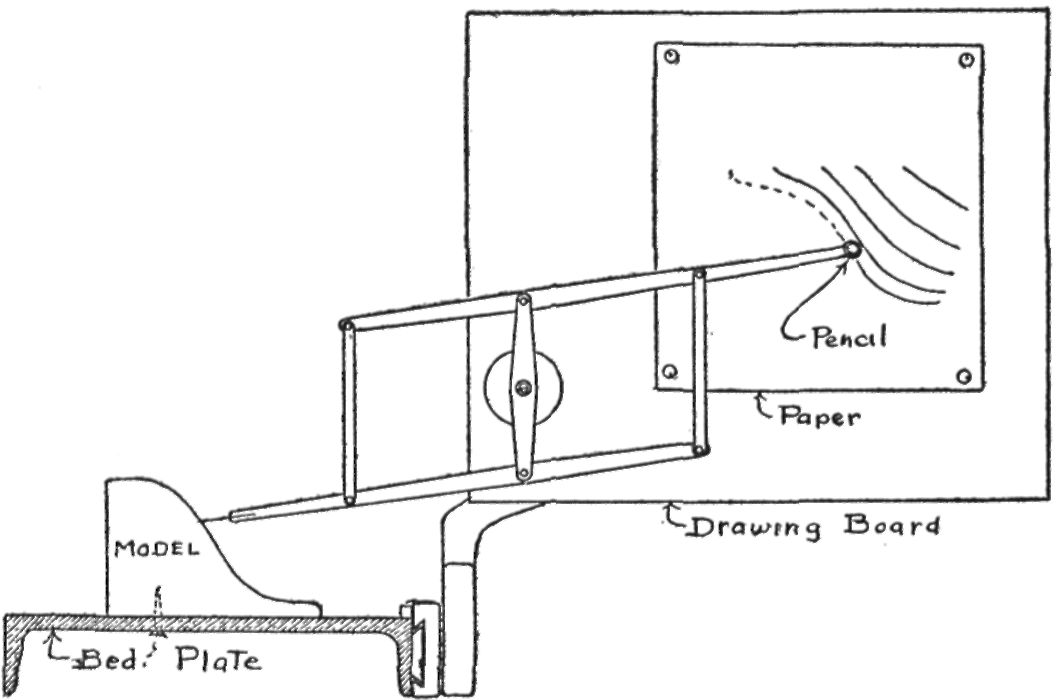

In fall of 1859 John decided to have a larger boat and Sprite was planned and modeled by my father & John, together, and I, at age of 11 1/2 did all the drawing and figuring for the full size moulds. The boat was built by my father and John in the Old Tannery after being begun by Mr. Wm. Allen Manchester who died in fall of 1859.

Launched June 28, 1860. 20' long, about 9' beam. Centre-board, about 1/2 ton of inside ballast (old grate bars) and 5 or 6 cwt. of shifting weights, part lead. Centre-board 6' 6" long and forward end 8' 10" from outside of stem. The mast is stepped quite near the stem, and boom very long. Has a bulkhead supposed to be water tight about amidships—from that there is a cabin trunk or house. The ash coaming 4" high begins at the house, and circles around 13" from the stern.

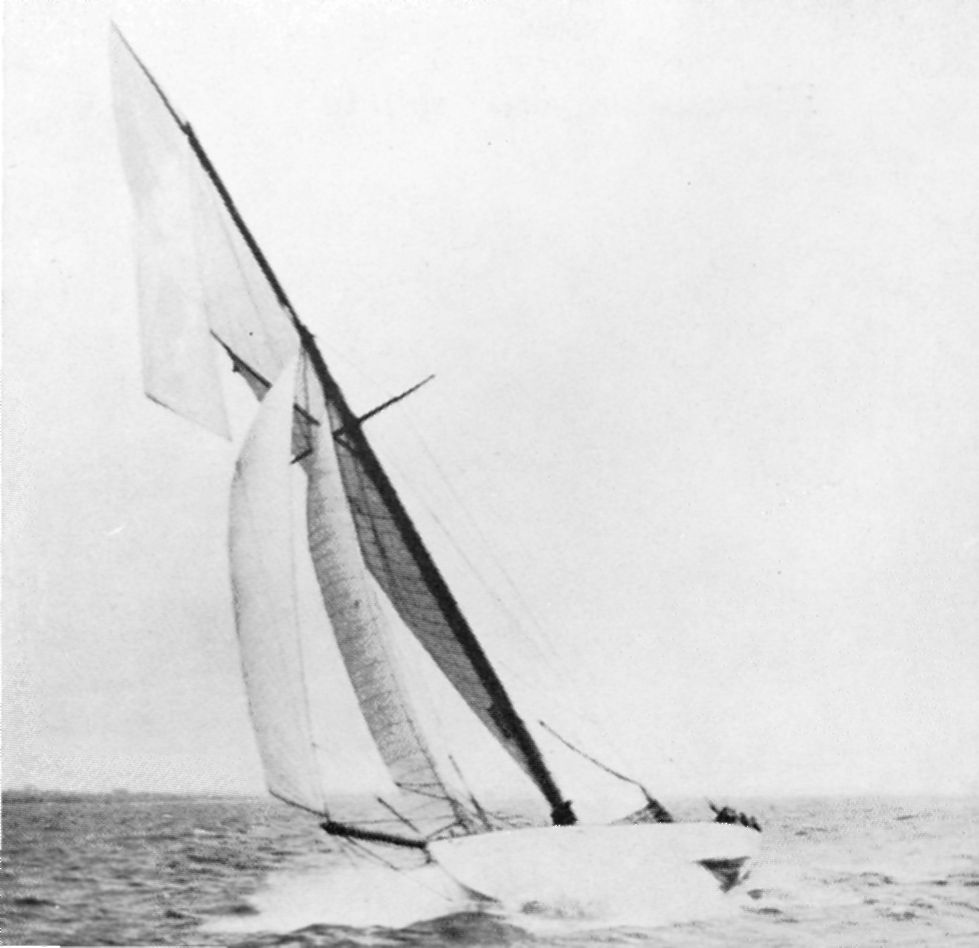

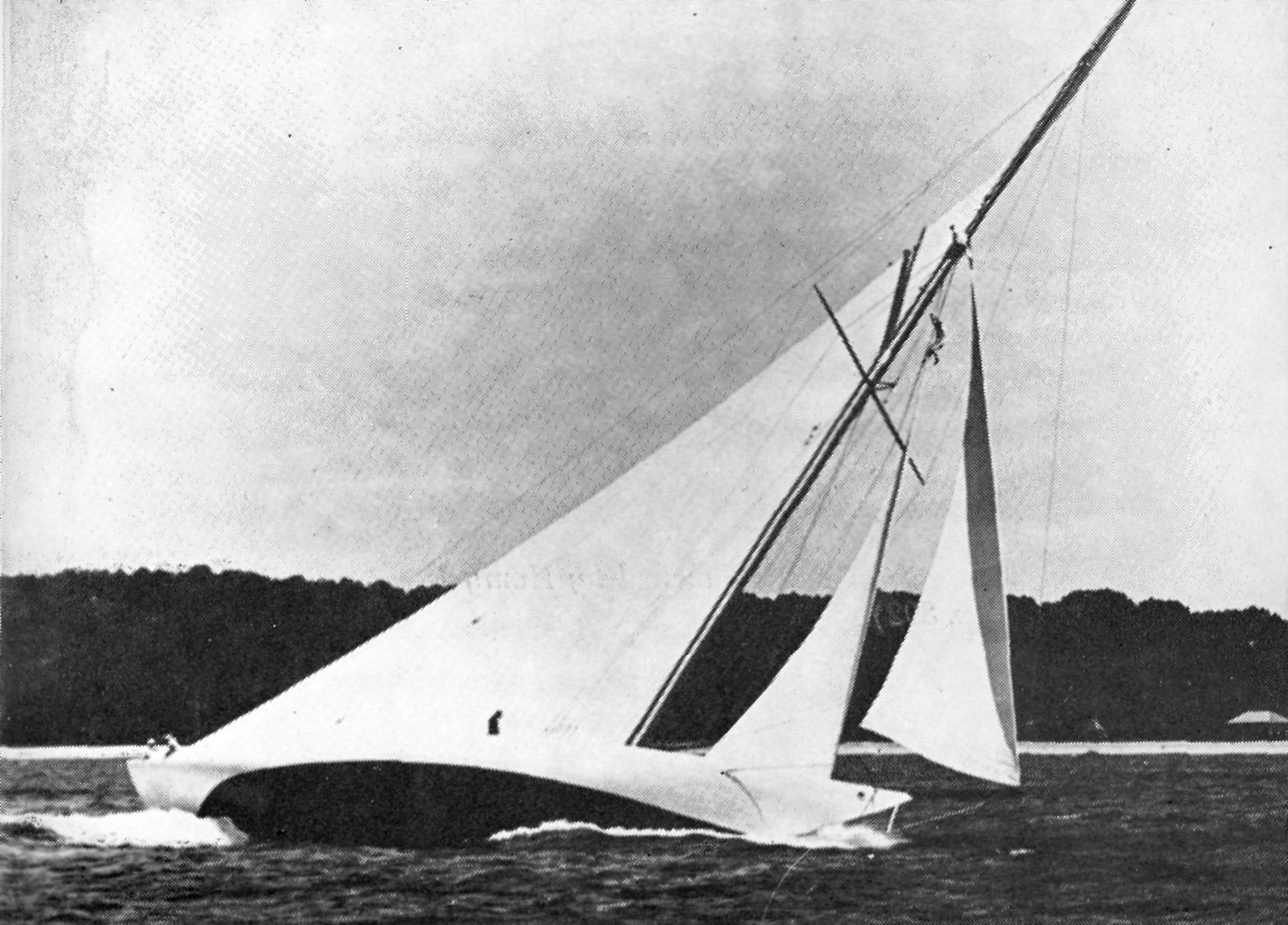

Sprite was very fast, and easily the fastest sailer in the Bay. But she was a brute to steer, due principally to the very long boom, wide and weak rudder.

When only a few weeks old she made a cruise to New York in company of my father's Julia (3rd). The crew on Sprite was John B., Georg C. D'Marini & self. On Julia, my father, (E. F. H.) James B. H., Lewis H. and Henry Slocum taken as pilot. The run was made in 27 hours in fog & light s. wind to Watch Hill, and brisk N.W. during night from New London to New York. The trip was specially made to see the steamship Great Eastern. She was anchored in North River, but we could not get on board. We stayed over two nights at Hoboken. Our trip home was made in 26 hours in a brisk south wind.

The latter part of summer Sprite had her first race. It was from Jerry Angels' Clamhouse—an old stern-wheel steamer moored a little north of Fields Pt. and twice around a course down the river in moderate n.w. breeze. There were two 24' boats of Ben. Appleton, the Planet, 25 ft. of Davis & Childs, and Sprite. Our crew was John, Lewis, Benjamin, Appleton, and myself as helmsman, (at 12 years). Planet 25' beat us a little, but we won easily on time allowance.

Sprite was going much of the time in three long seasons. The longer cruises were to New Haven, Block Island, Vineyard Haven & Clinton, Conn.

By this time the Civil War had started and prices of food and other commodities were going up which must have been quite alarming to Charles Frederick Herreshoff living on a modest income with nine children, four of whom had lost their eyesight. But he succeeded in giving three of them a college education and helped to start almost all of them off on a career.

Charles Frederick was a large, strong, broad-shouldered man with a quiet, patient disposition. He had inherited strong characteristics from the Brown family for which he must have had a high regard, since four of his children had Brown as a middle name. He died in 1888 at the age of seventy-nine, and his wife, Julia Ann, although frail in the latter part of her life, lived to the age of ninety, dying in 1901.

I have not said much in this chapter about Captain Nat's brothers and sisters for this chapter is intended to describe his ancestors and his early life, but in the next chapter his brothers will be written about separately for most of them were somewhat famous in their particular lifework.

To sum up Captain Nat's inheritance—several of his ancestors had been ship captains or shipowners, and that would account for his nautical tendencies. His great-uncle, James Brown, seems to have been a very talented architect, so from the Browns he may have inherited his refined sense of proportion. I believe he received many other valuable traits from the Browns, not the least of which he liked to refer to as common sense. No doubt from the original Prussian Herreshoff he inherited stubborn determination, conceit, and self-sufficiency, and while these last characteristics do not seem desirable still they are absolutely necessary in designing. Conceit gives confidence, and self-sufficiency helps in making decisions, and designing or any other planning is mostly a matter of making decisions. Yes, endless decisions of shape, weight, strength, and methods of fabrication, and he that lacks either confidence or common sense should not attempt designing. Captain Nat was high strung, so to say—super-sensitive and easily irritated. Perhaps these traits are necessary for high accomplishment.

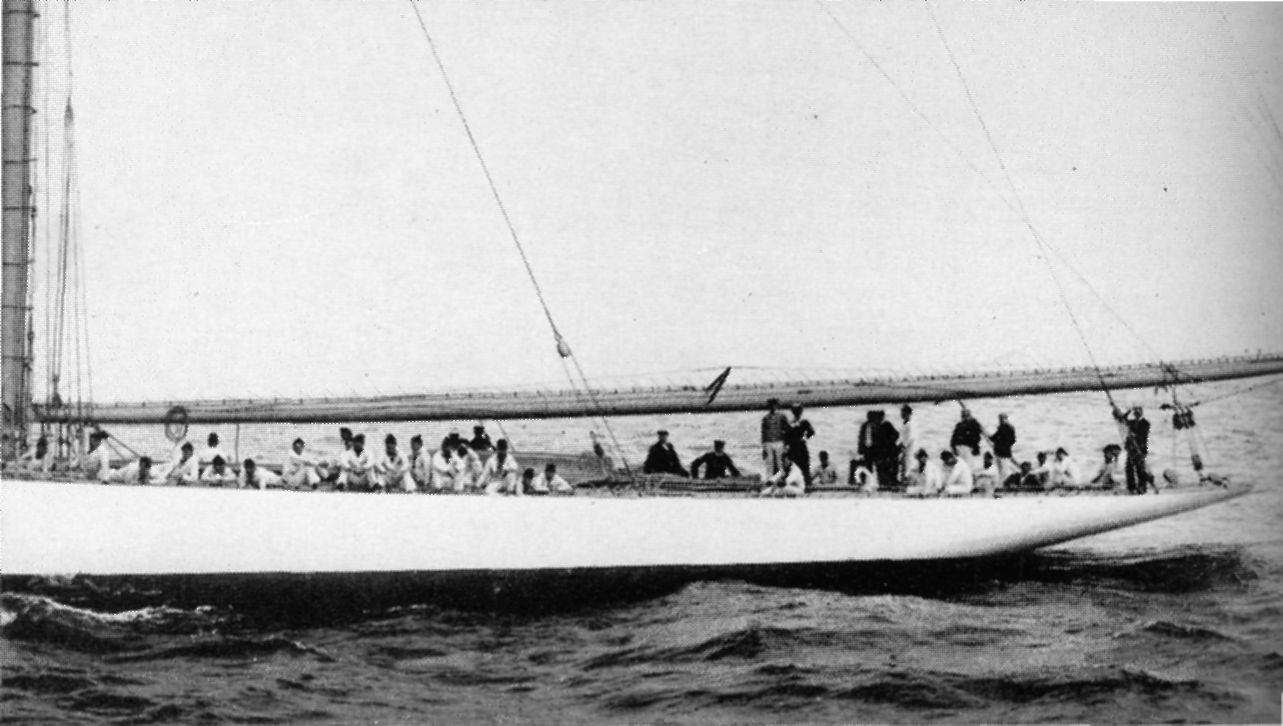

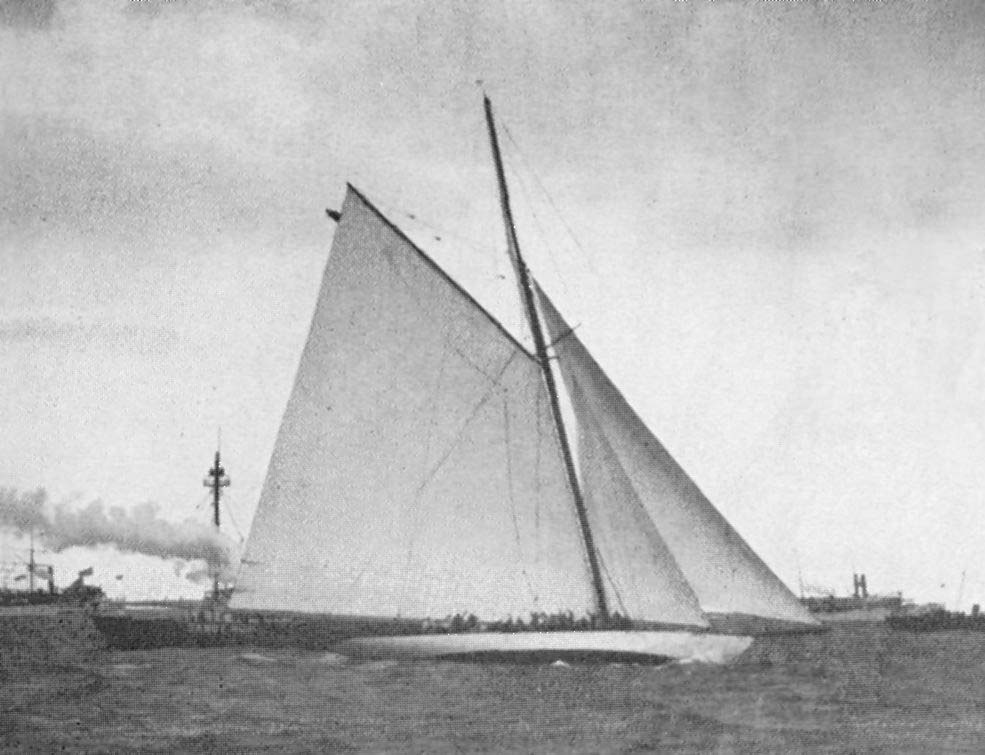

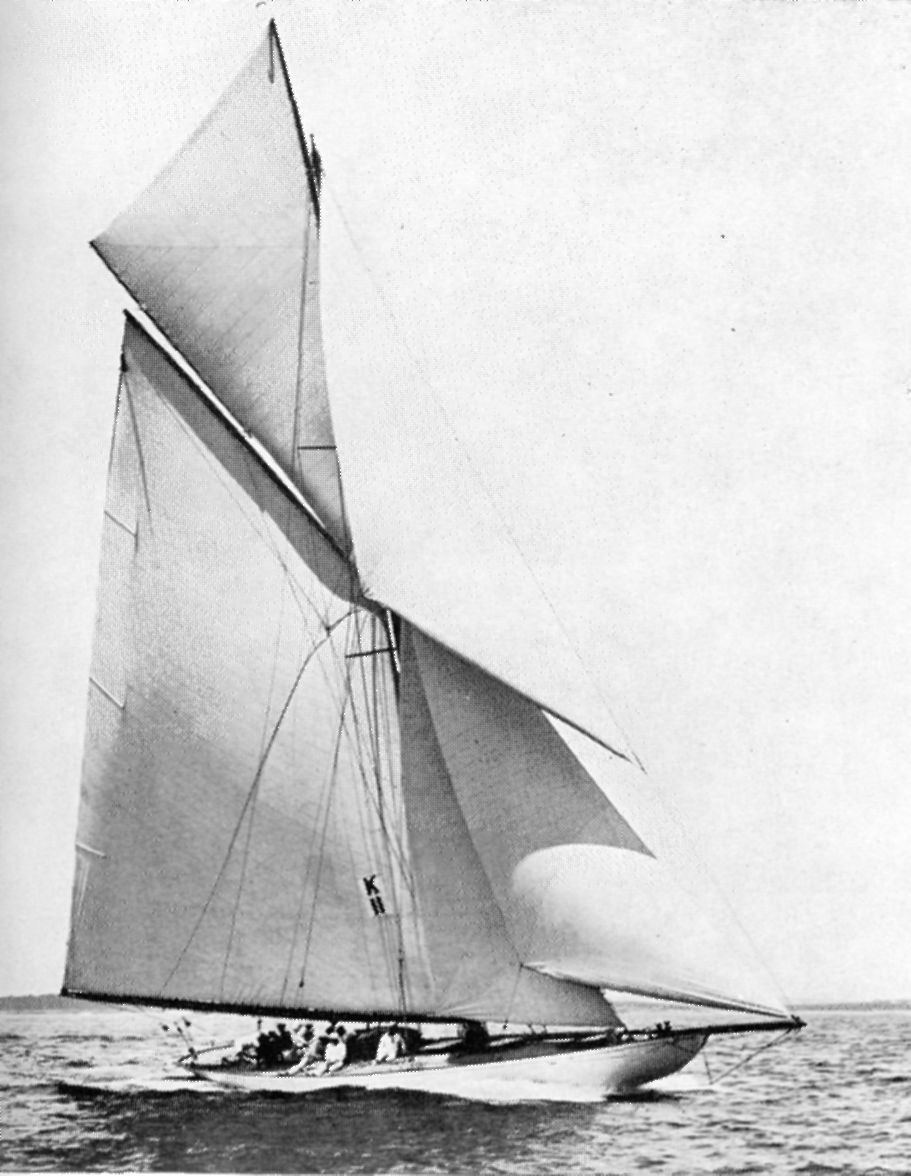

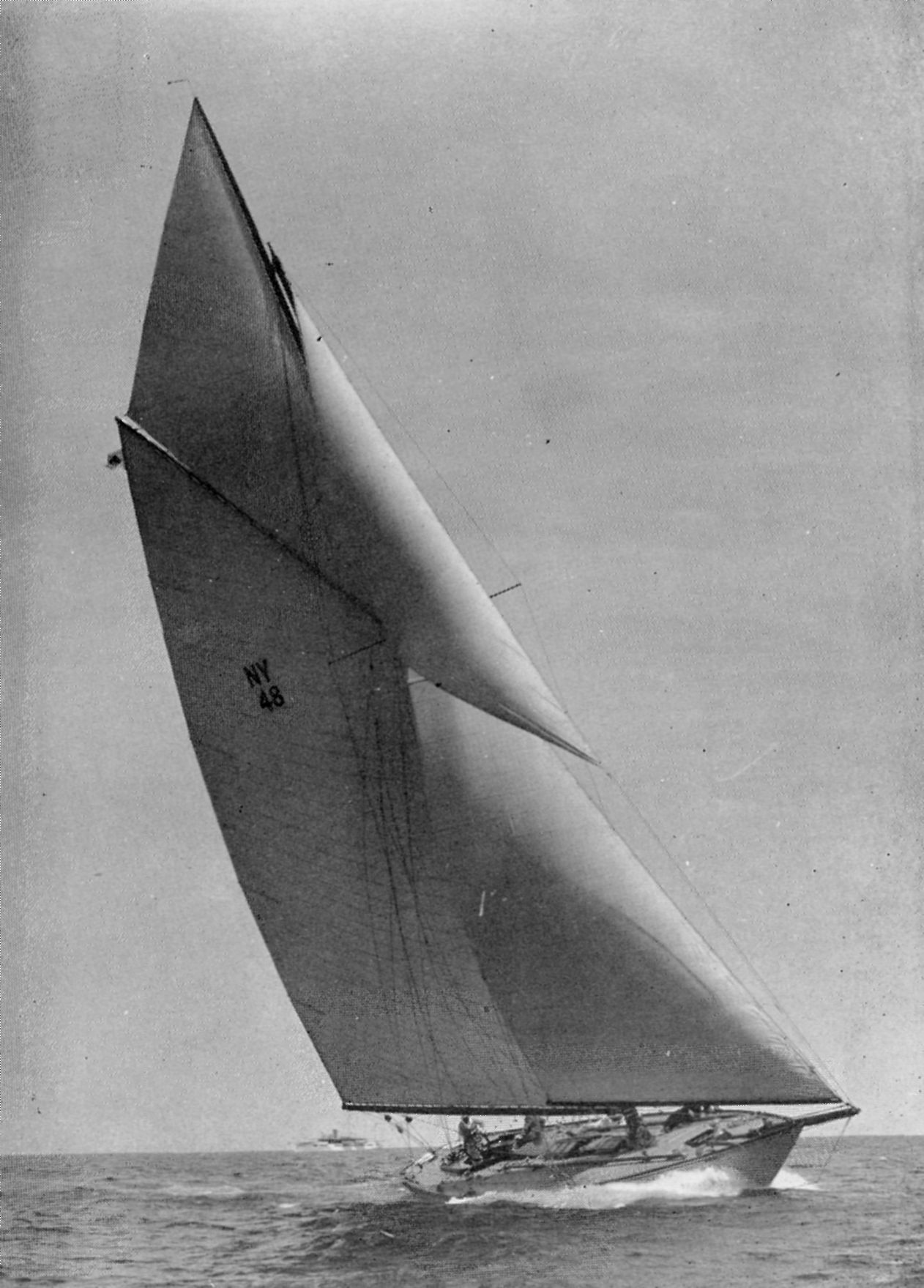

Naturally Captain Nat absorbed many of his mother's ideas and peculiarities for he was very fond of her. Julia Ann, among other things, was a strong prohibitionist or teetotaler but Nat even outdid her for he would not even take tea, coffee, or any stimulant whatsoever. The story is that the only time he took a drink was when the Columbia beat the Shamrock in the final race of 1899. It was on October 20 and a cold day, with a strong northerly wind, and Columbia had just beaten Shamrock six minutes in a magnificent fifteen-mile thrash to windward. The afterguard was celebrating the victory right after the finish, and Mrs. C. Oliver Iselin, who had sailed through the season on Columbia, persuaded Captain Nat to have a drink.

Another thing this mother impressed upon the minds of her children was the value of truth, and none of her children were exaggerators in conversation. But truth is of even more value in engineering matters than in financial or personal affairs; perhaps truth is the most essential factor for logical thinking. It is probable that Julia Ann inherited her love of truth from the Winslow side of her family, for the Latin motto on the Winslow crest, "Decoptus Floreo" may be translated to English as Truth crushed to earth shall rise again.

This chapter will be used to describe Captain Nat's brothers and sisters for it will give the reader a clearer understanding of the ones who will be mentioned later, and because there is much confusion about just what some of them did or did not do. The chapter is called The Herreshoffs

for in about 1890 there were no other Herreshoffs in the world that we know of except these brothers and sisters and their children.

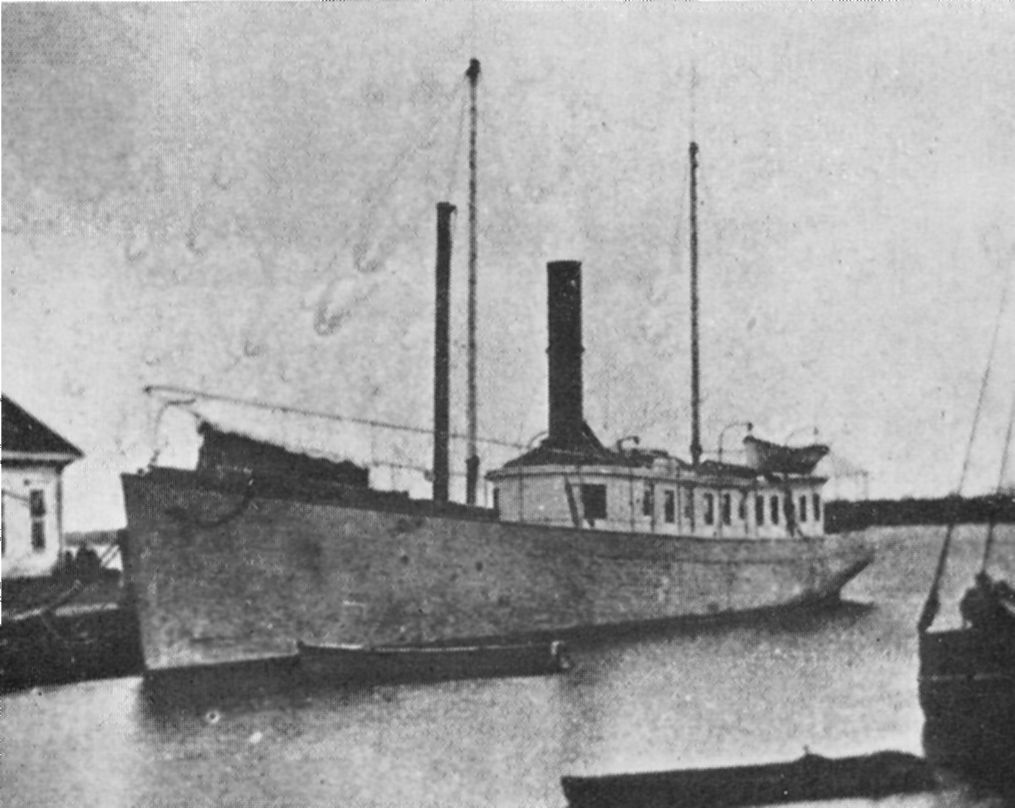

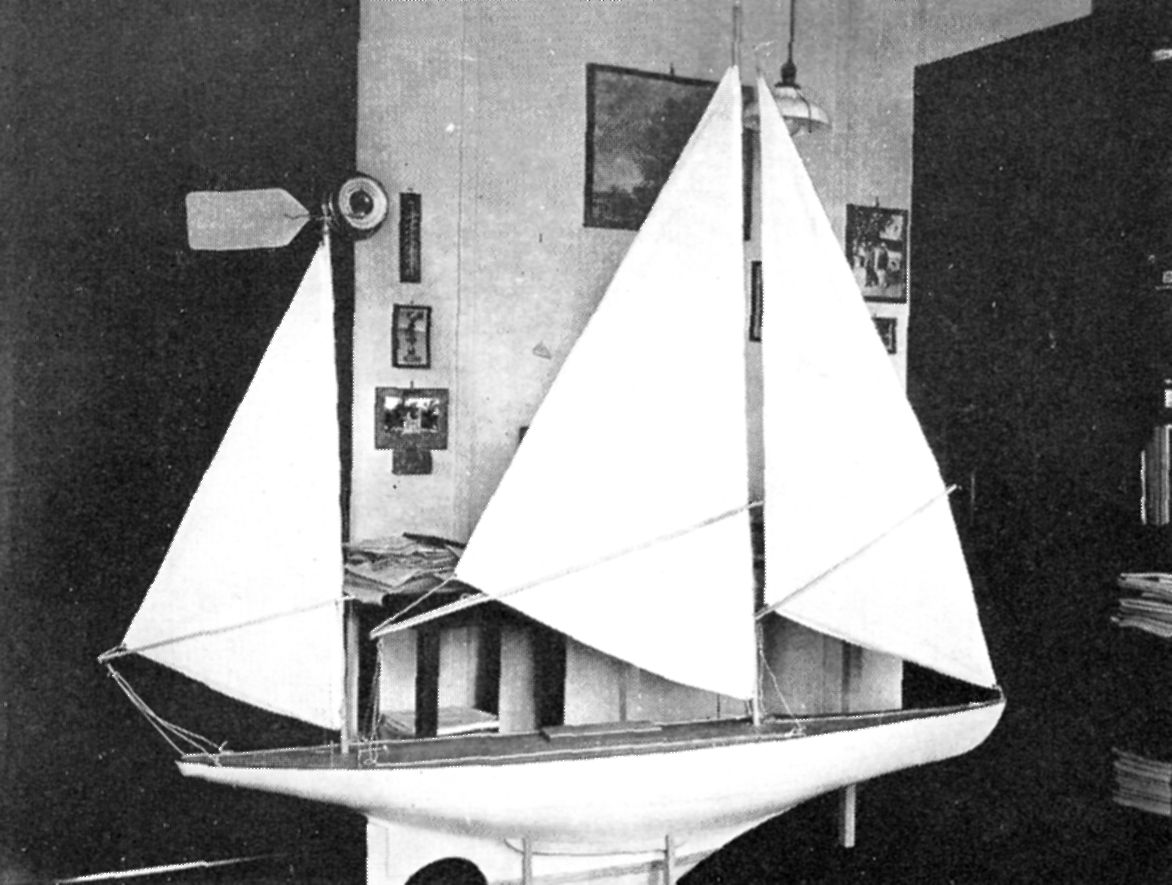

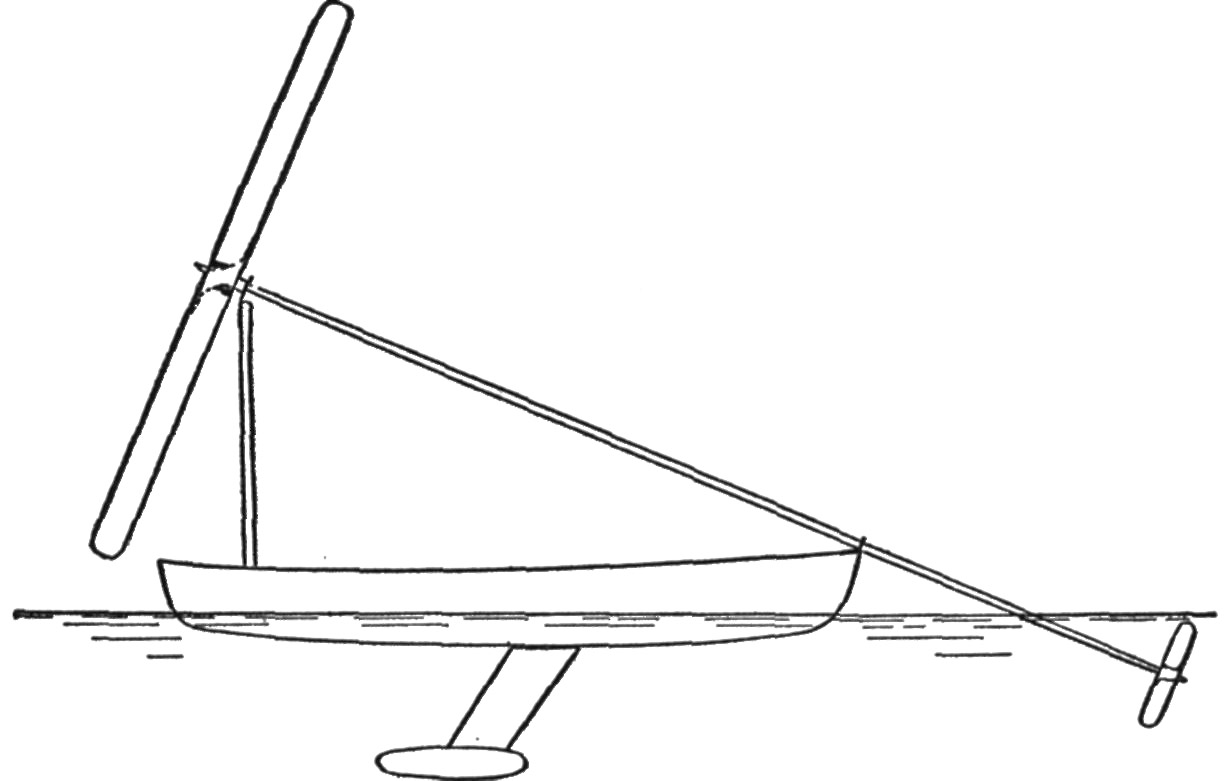

The eldest child of Charles Frederick Herreshoff and Julia Lewis Herreshoff was named James Brown Herreshoff, born in 1834. In his youth James showed a strong inclination to experiment and invent, and one biographer, at least, has called him an inventor. While I have no intention of enumerating all of his inventions and experiments, a few of the most interesting or amusing will be mentioned. It is said that his first invention was a stool on runners to sit on while weeding the garden. In those days onions was the principal crop raised on the farms at Bristol, and the long rows were generally weeded by hand. Some people tied burlap bags around their knees and did the work kneeling—a very tiring work indeed. But Jimmie preferred to sit at ease on a seat on runners, and as he was only about fourteen years old, it was considered a good invention. He experimented with windmills quite a lot and developed a boat with a windmill connected to a propeller. When the size and pitch of both the windmill and the propeller are correct this type of craft will go to windward faster than a model yacht of its size, but it only performs well in strong winds, and for some reason or other a large one will not go materially faster than a small one.

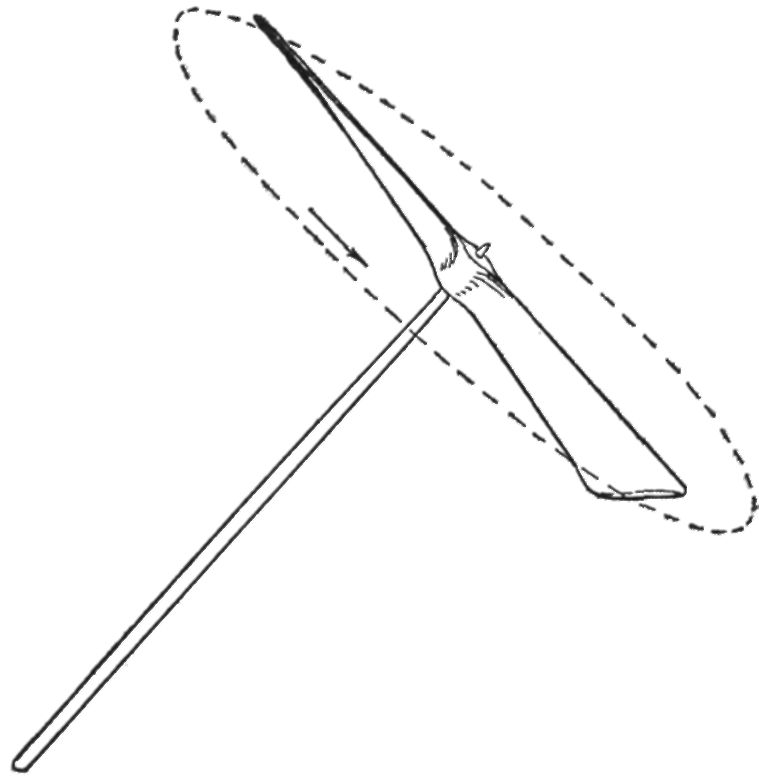

Jimmie also developed what he called a "go-devil" which was simply a windmill or propeller on a stick, and when the propeller is carefully shaped this contrivance will fly to elevations of about fifty feet. It is run or flown by placing the stick under the propeller between the palms of the hands. Then by sliding the palms one by the other in the right direction the propeller will be so rapidly revolved that what with the momentum of the revolving blades it will screw its way up into the air. But it must be carefully shaped to fly well.

James attended the scientific department of Brown University. After being graduated in 1853, he became a manufacturing chemist connected with the Rumford Chemical Company near Providence, and between 1855 and 1862 developed what was then called cream of tartar powder, later called baking powder. Although quite a young man I believe he made enough through this baking powder development to live on most of his life. In 1862 he began the manufacture of fish oil and fertilizer derived from the large quantities of menhaden in the bay, and this industry, in other hands, became a large and successful business.

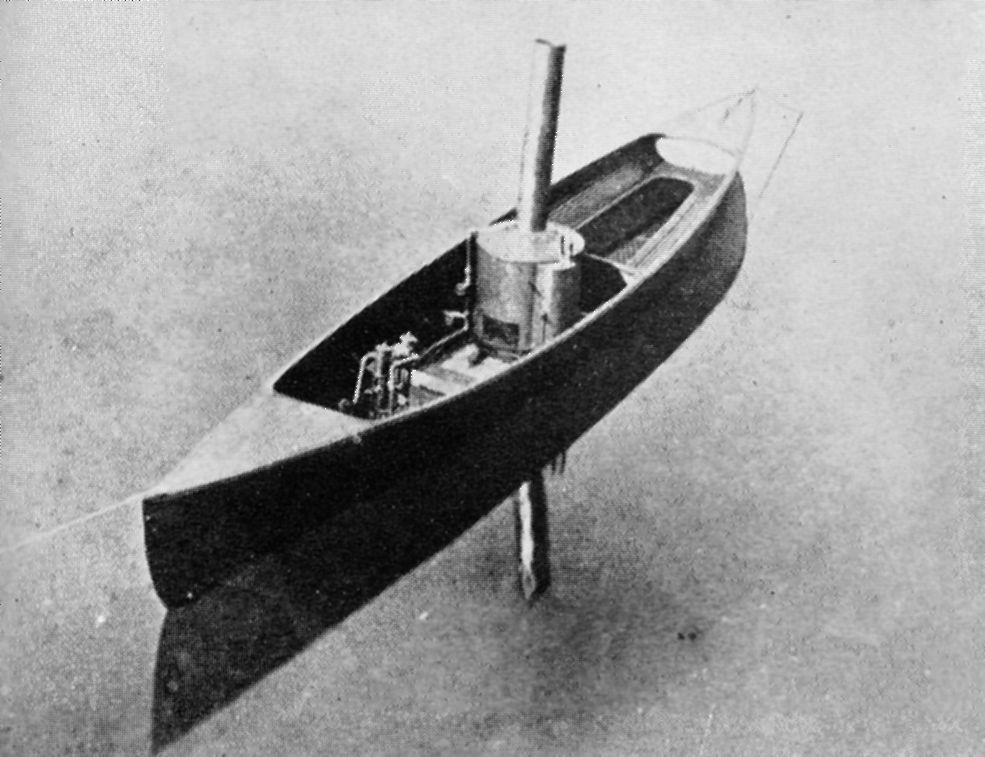

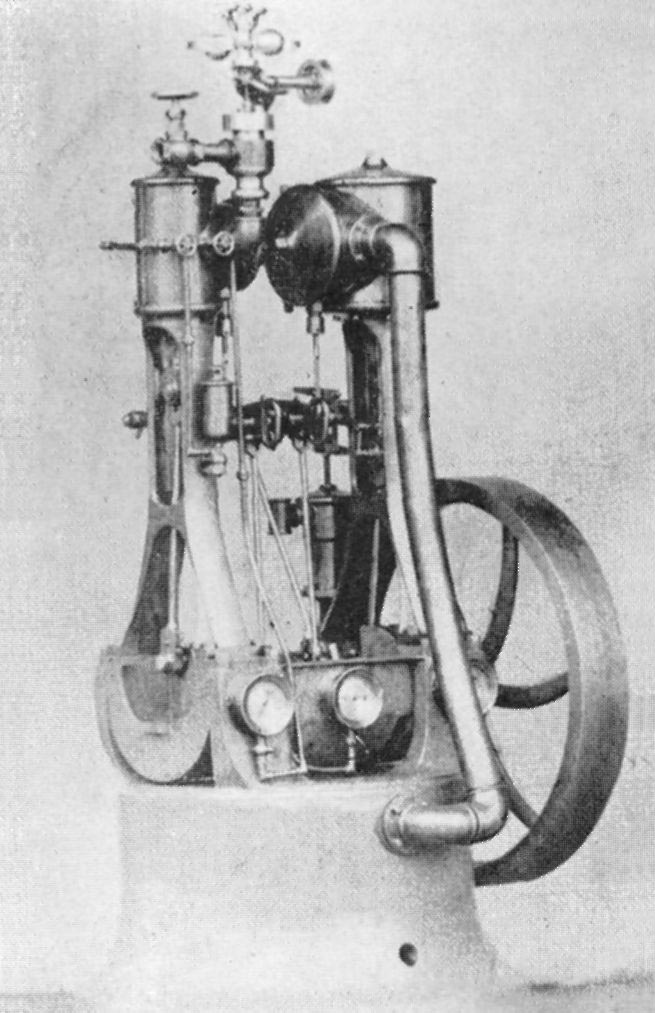

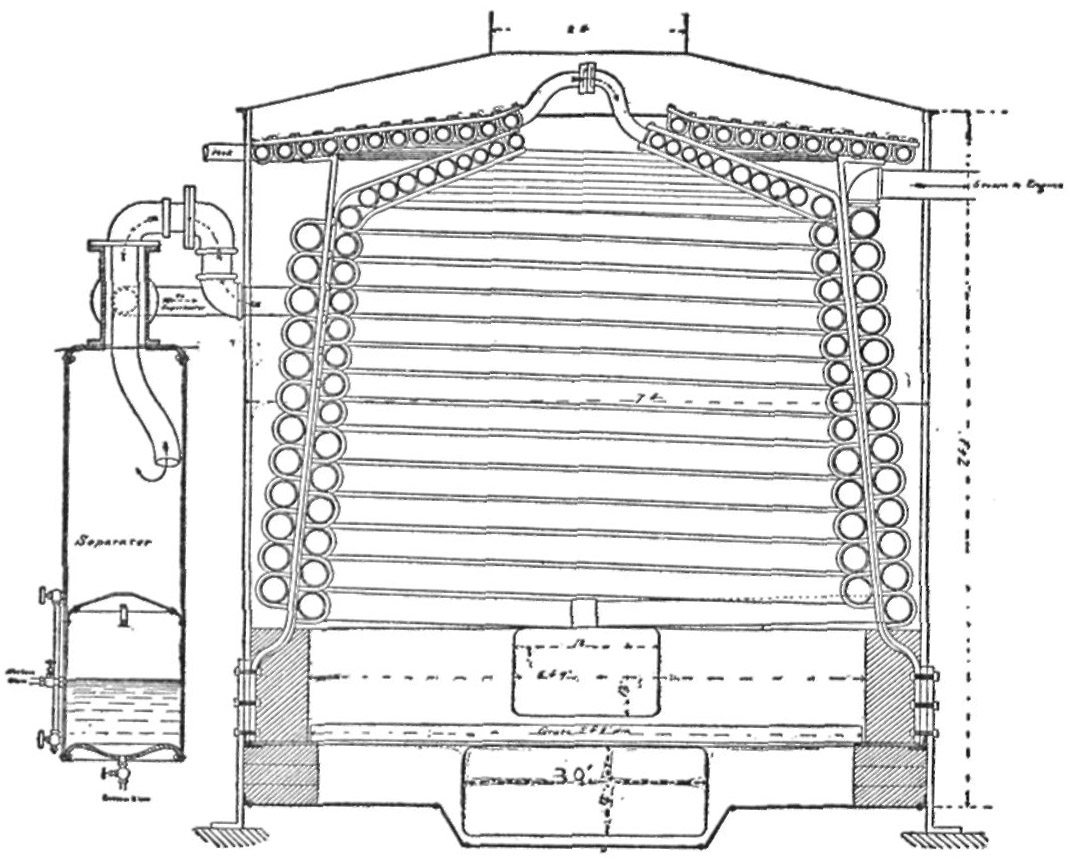

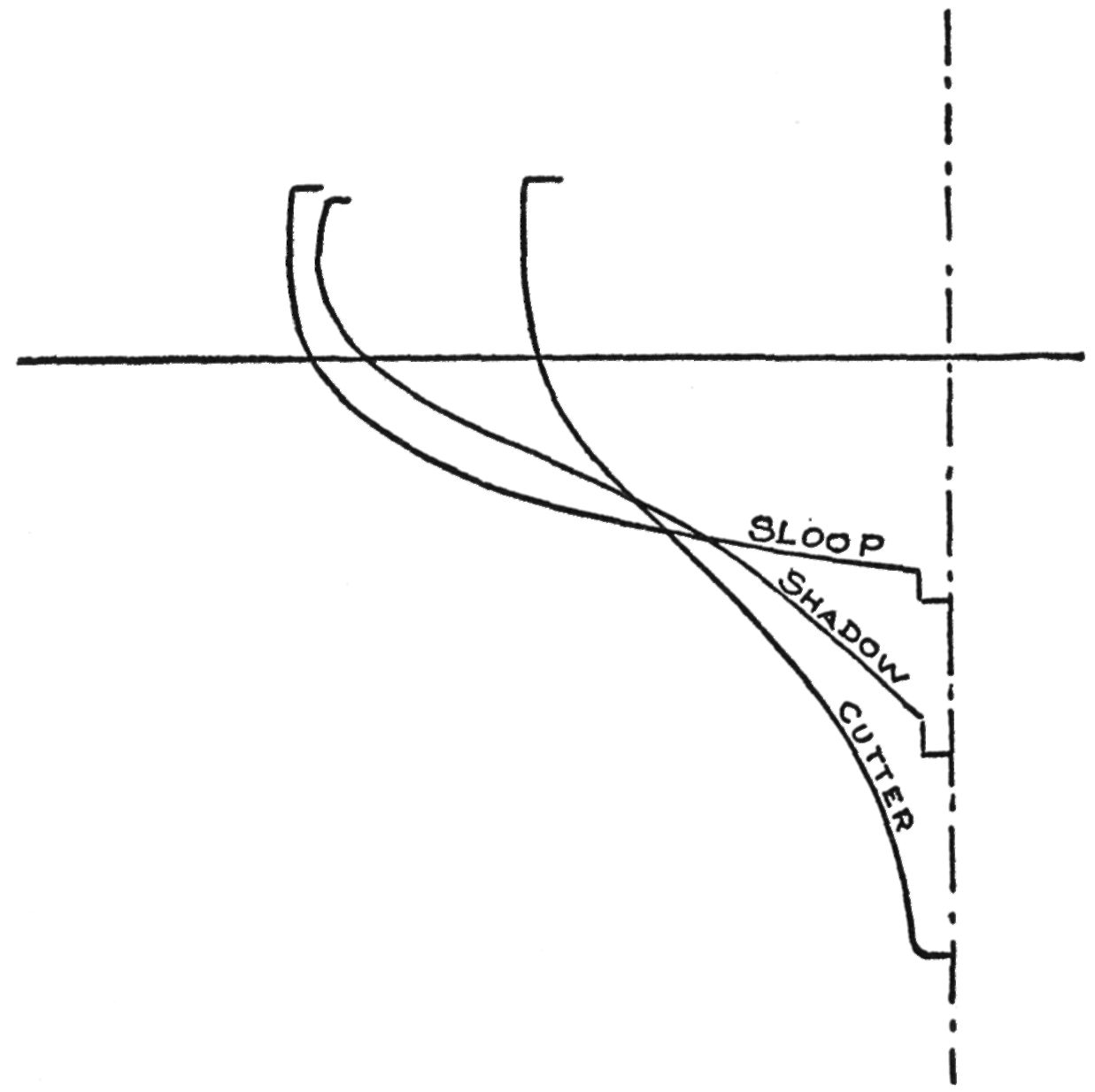

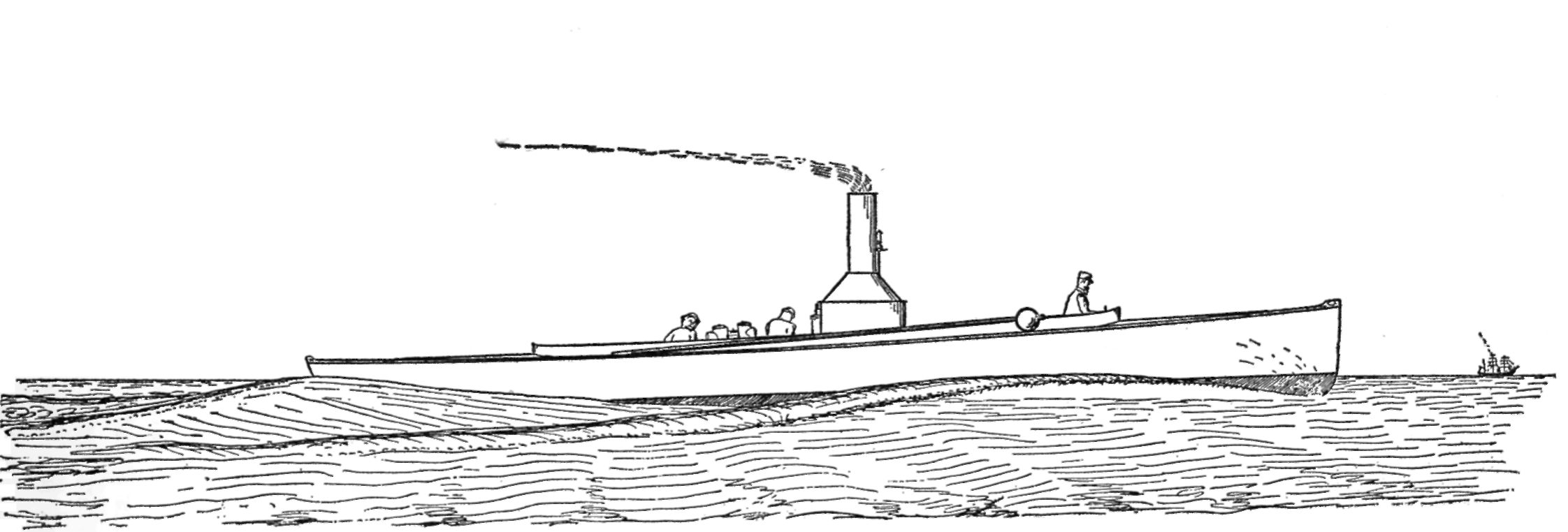

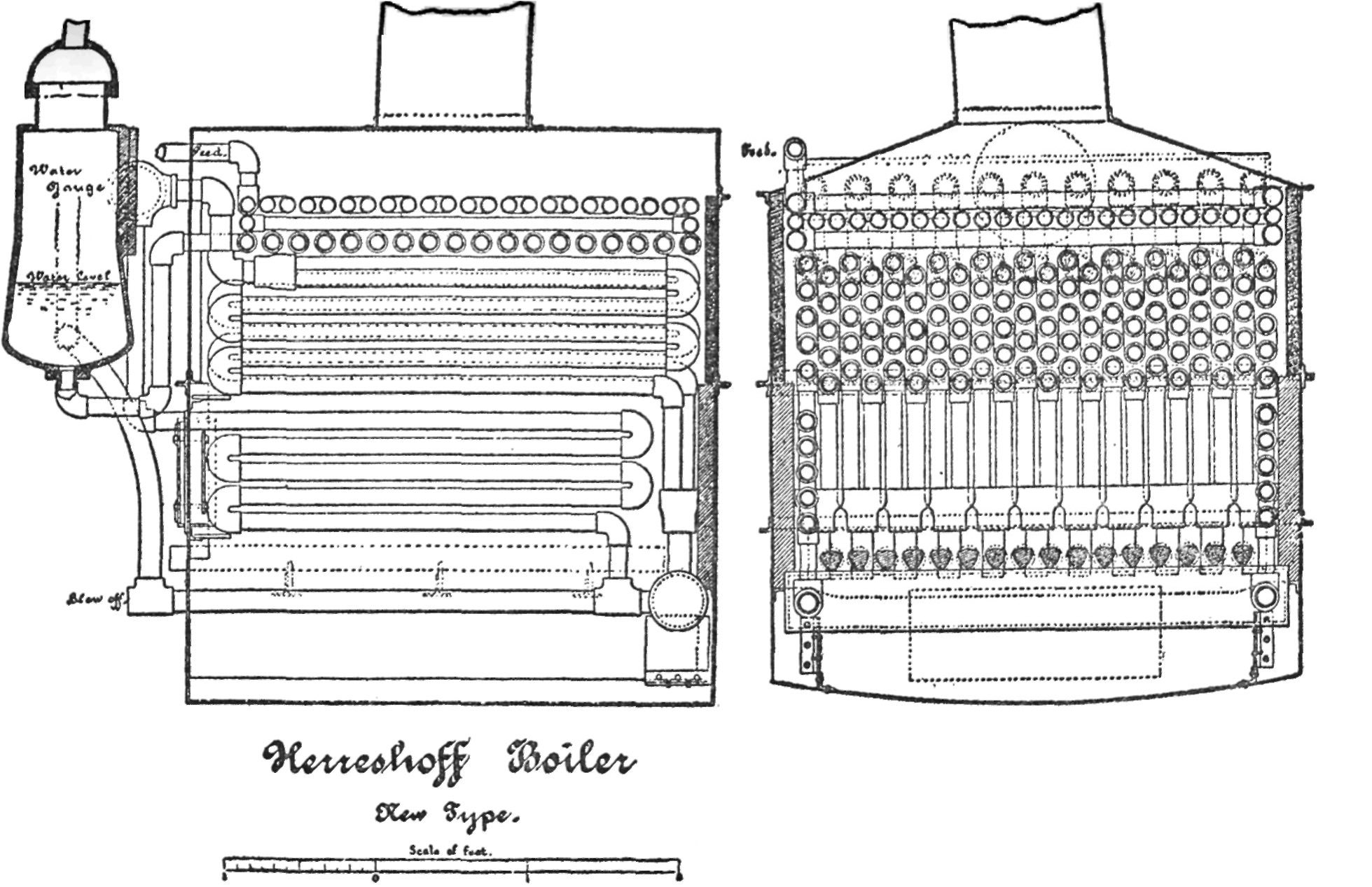

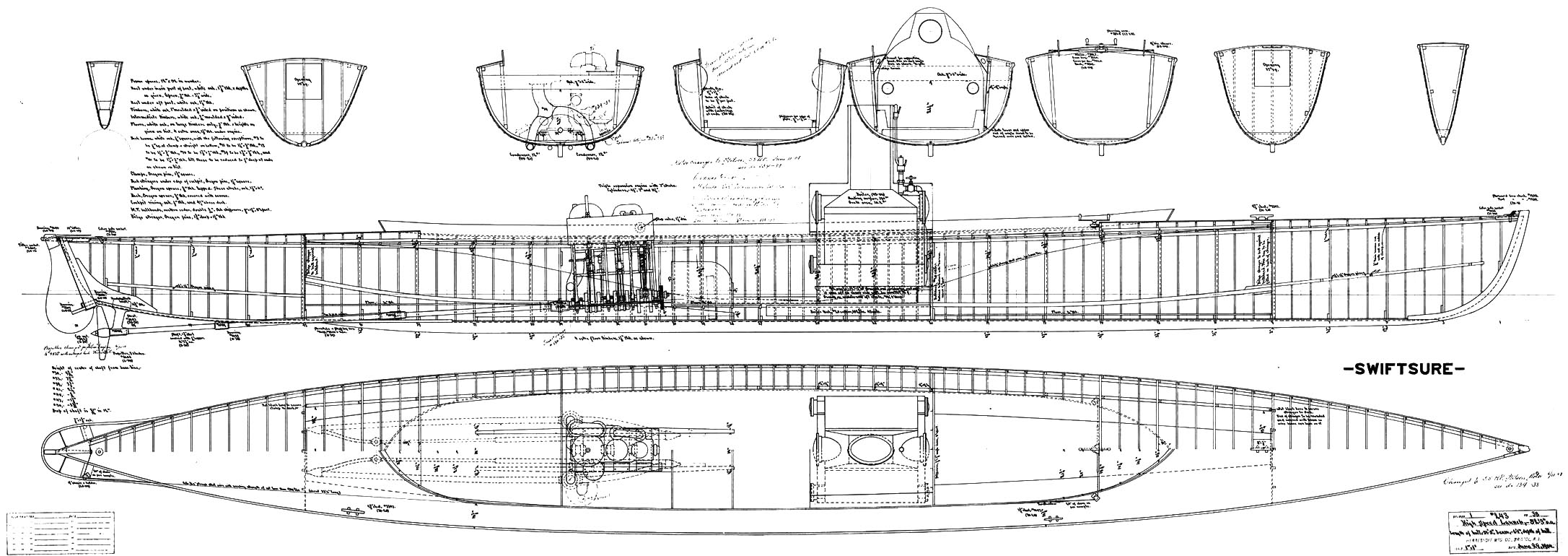

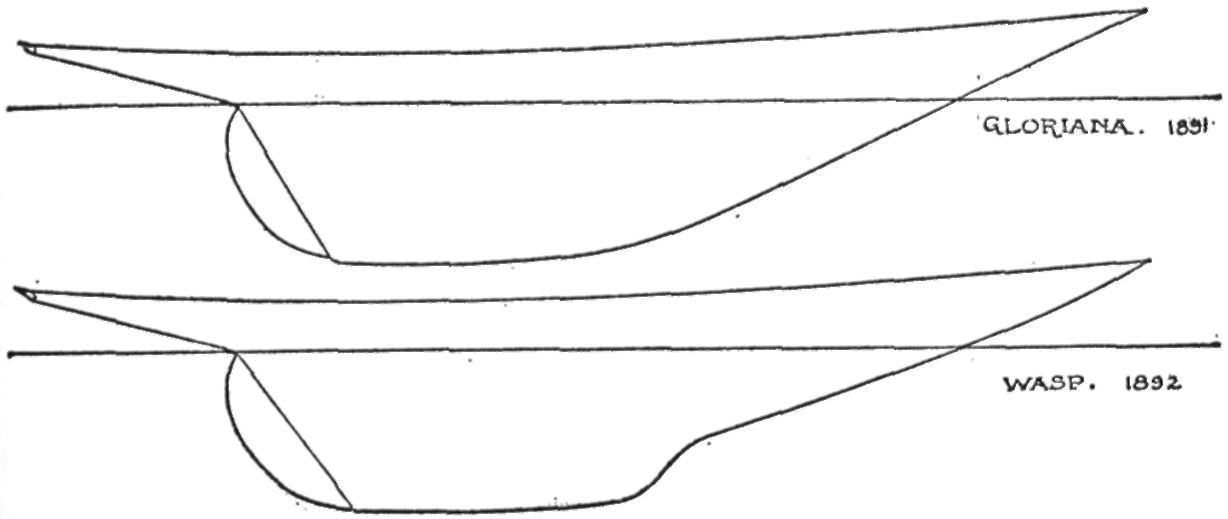

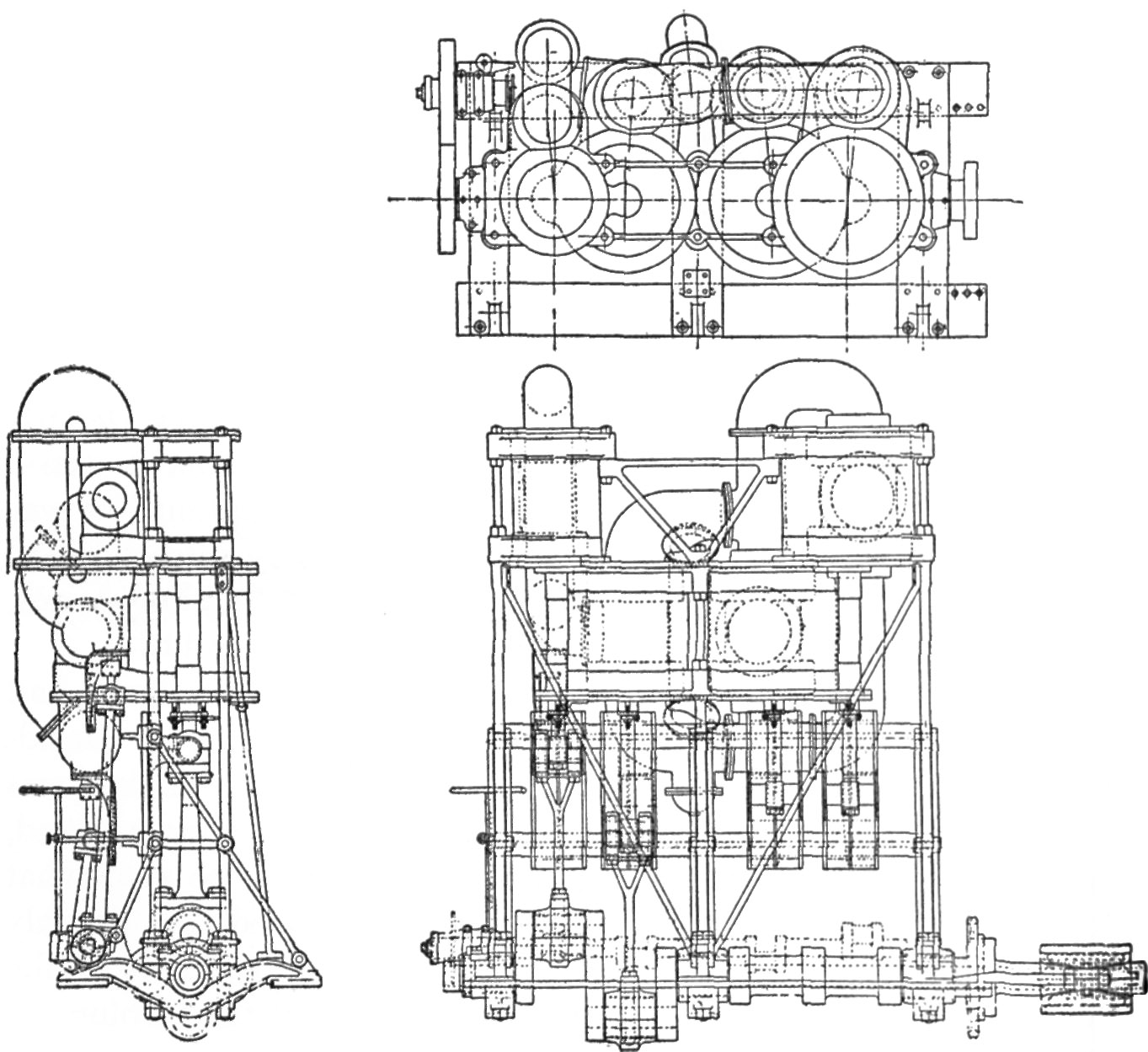

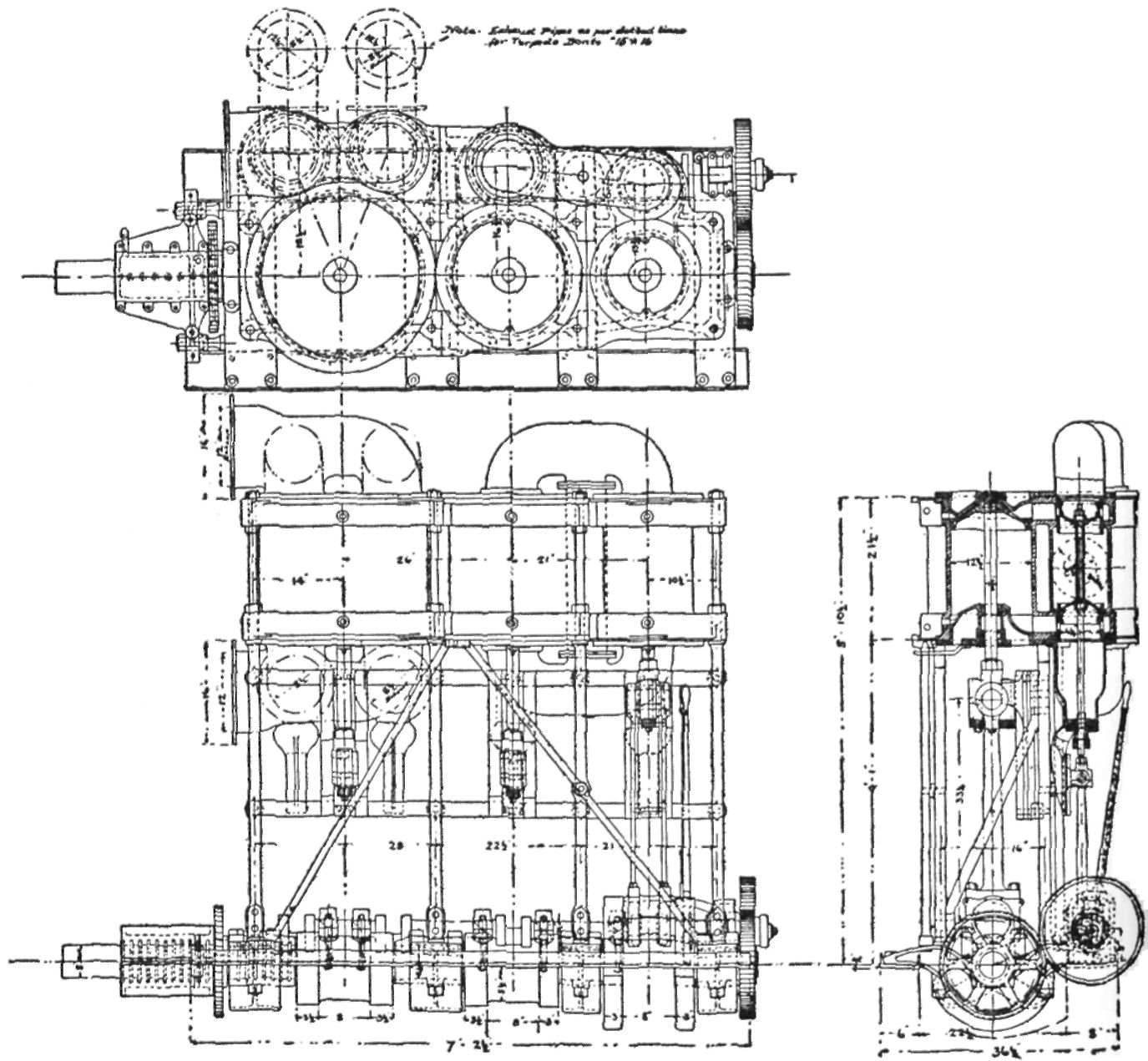

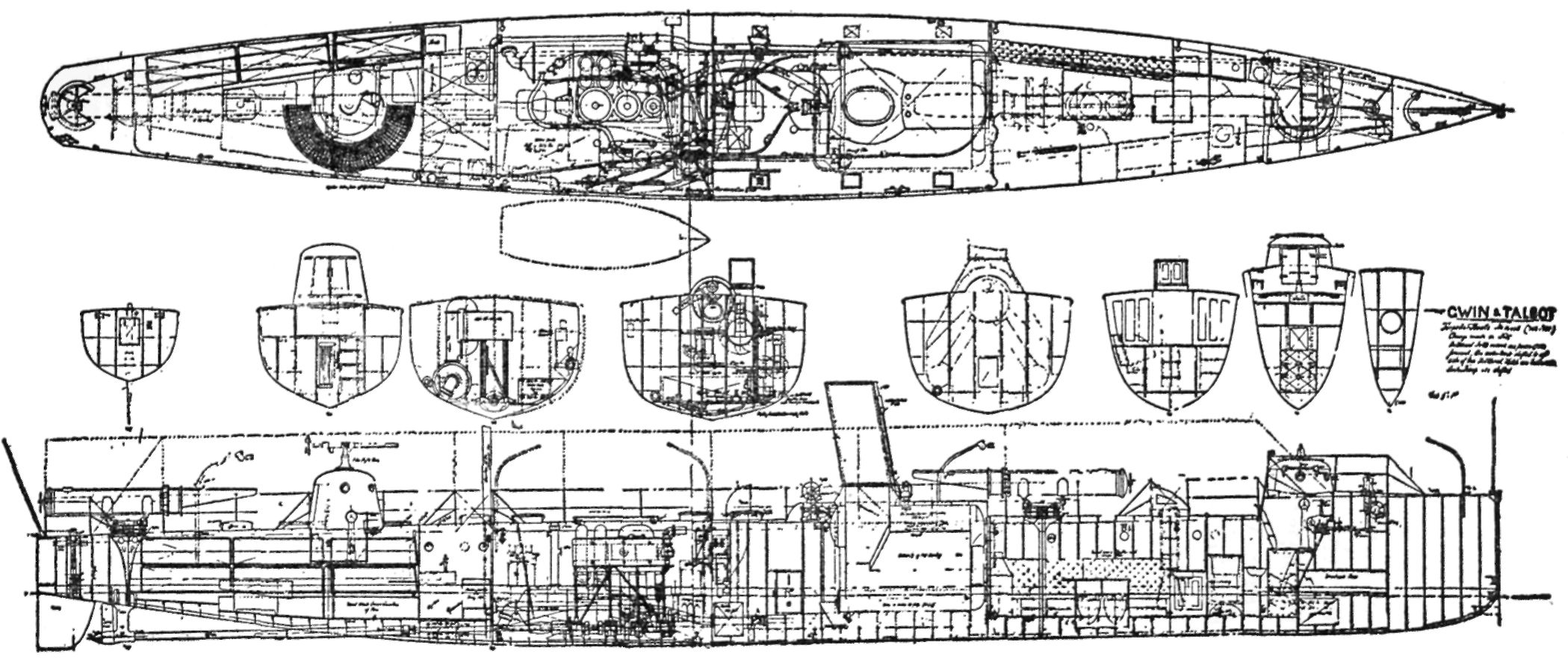

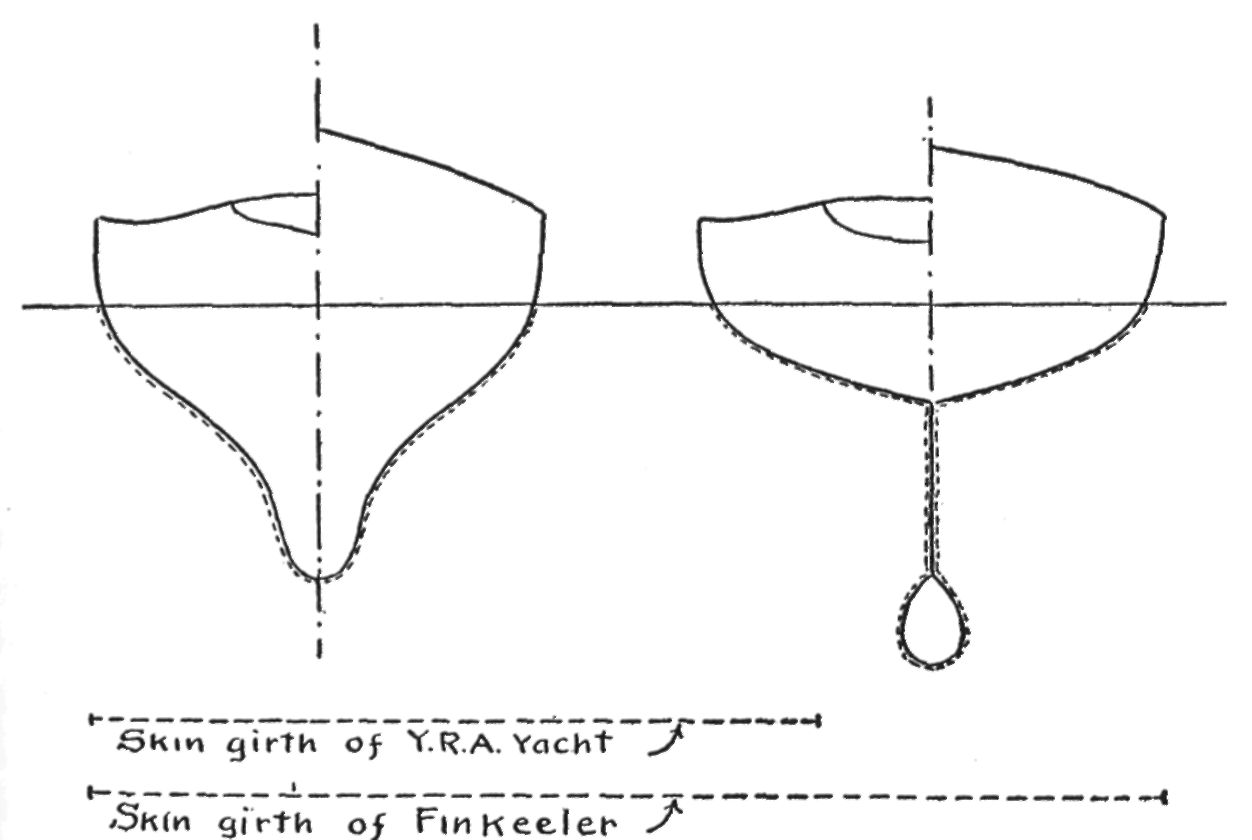

In 1873 he experimented with steam boilers and, in conjunction with Captain Nat, developed the so-called coil boiler of which we will speak later and will now only mention that it was the lightest steam generator of its time. He is also credited with inventing the fin keel for sailboats about this time, but I believe he only used this invention on model yachts. While the first successful fin keeler, Dilemma, was not built until 1891 (she will be spoken of later) there is no doubt that James experimented with model fin keelers both on windmill boats and sailboats, but Captain Nat told me that the fin keelers antedated both James and himself.

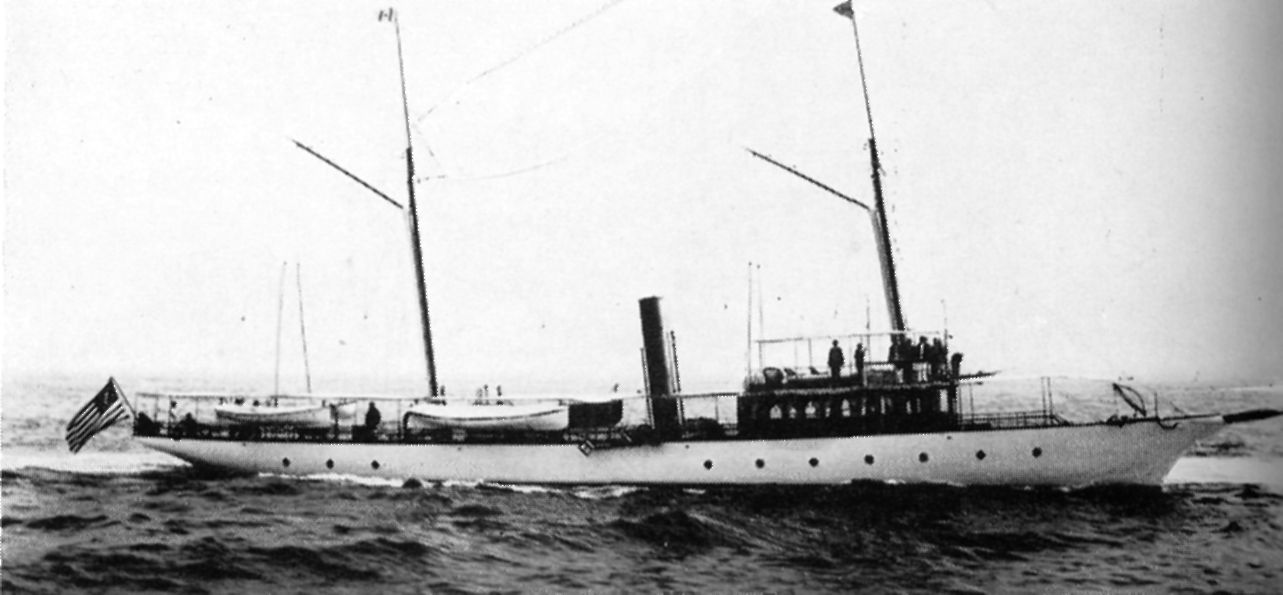

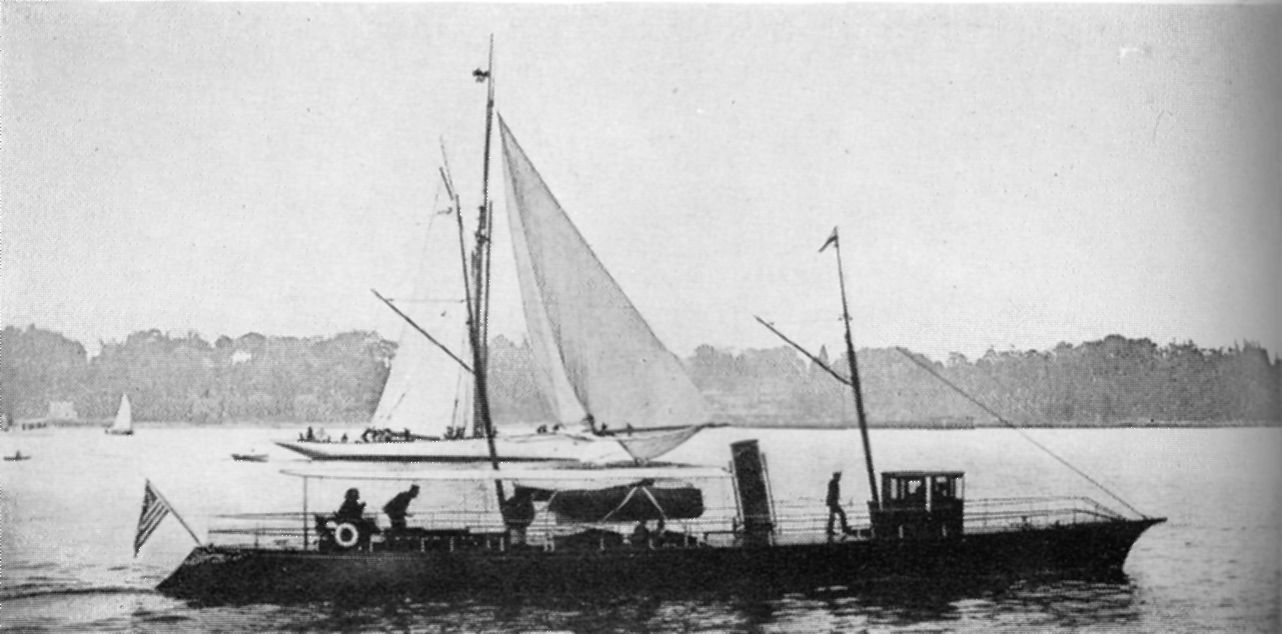

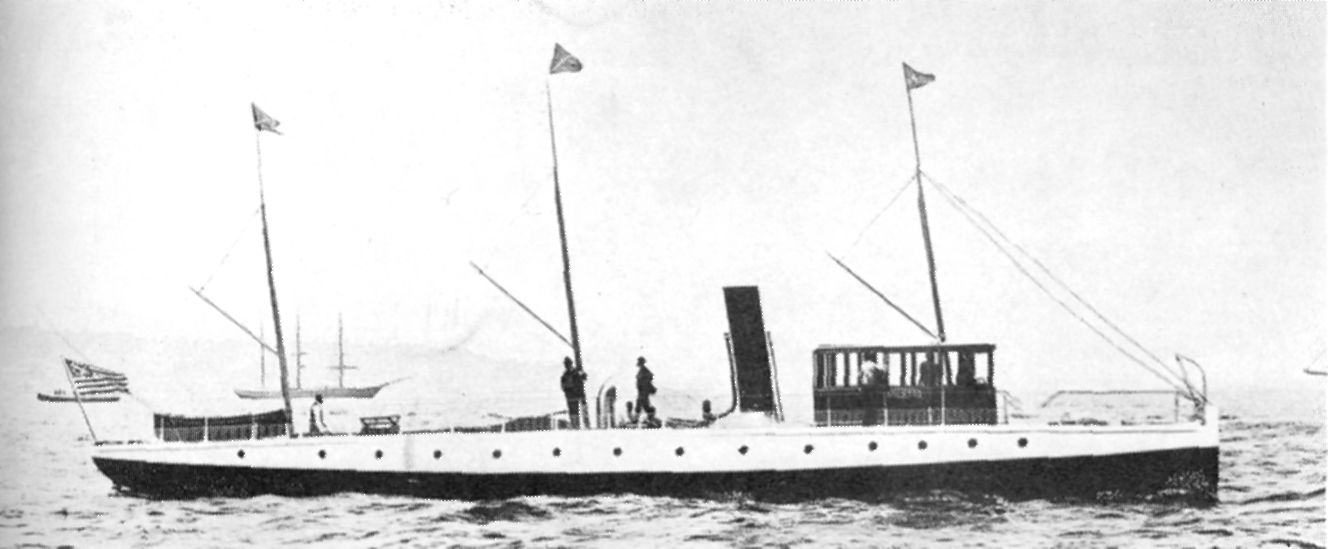

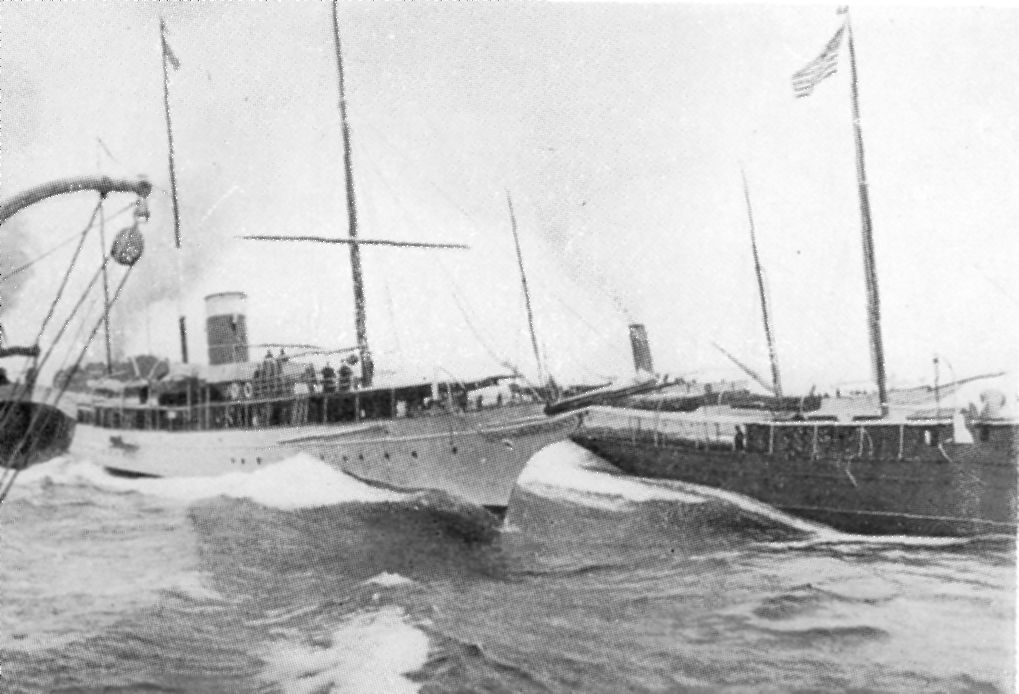

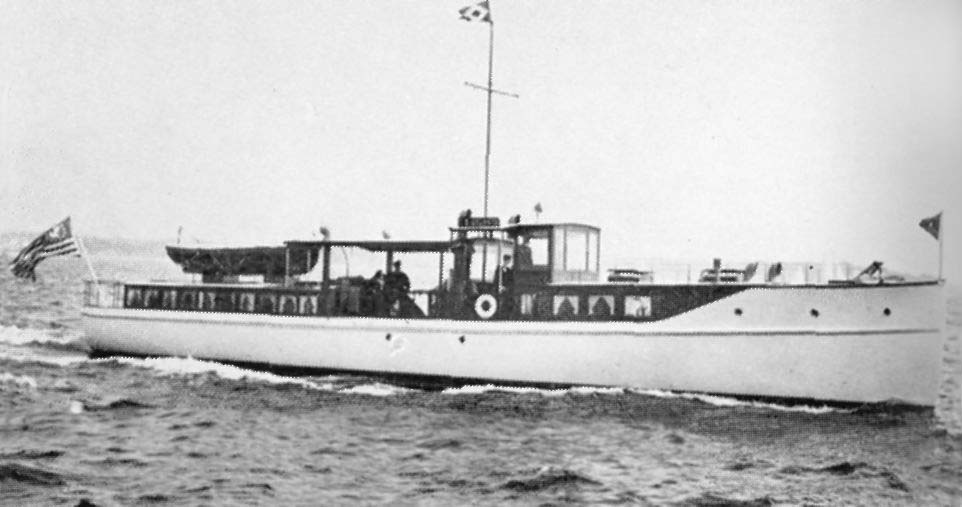

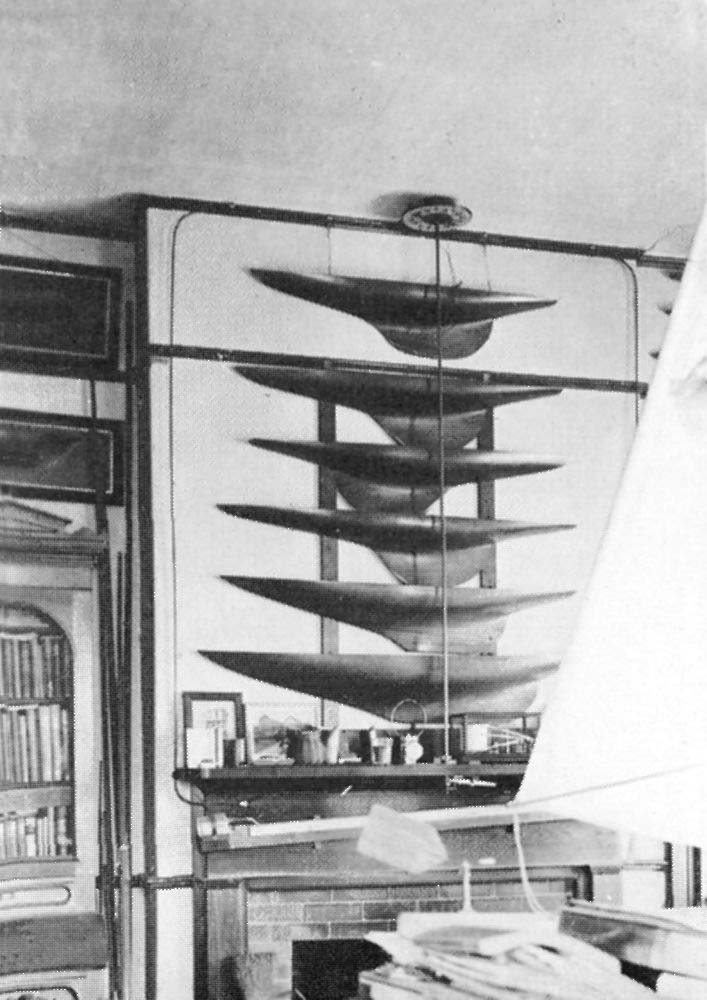

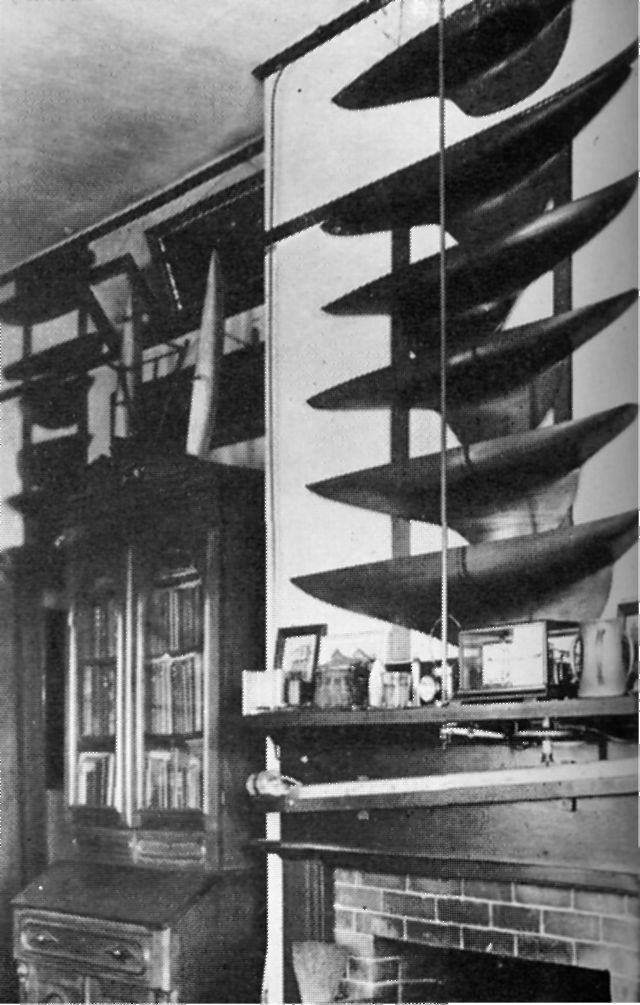

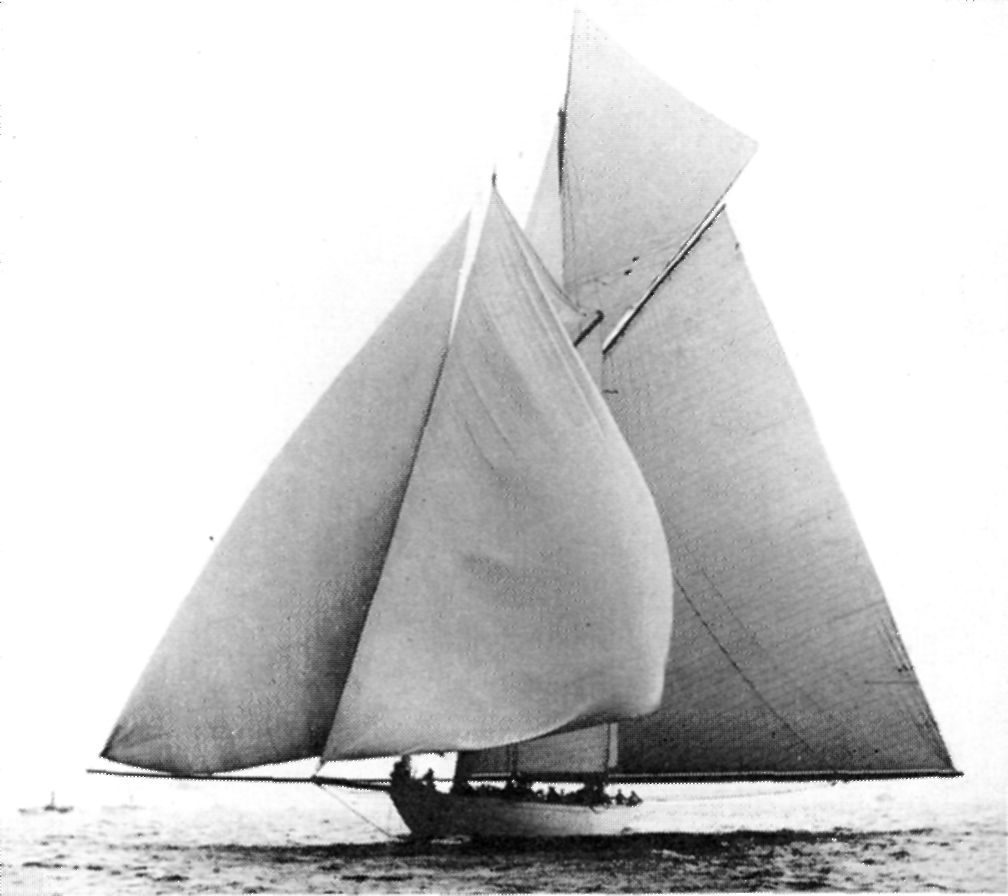

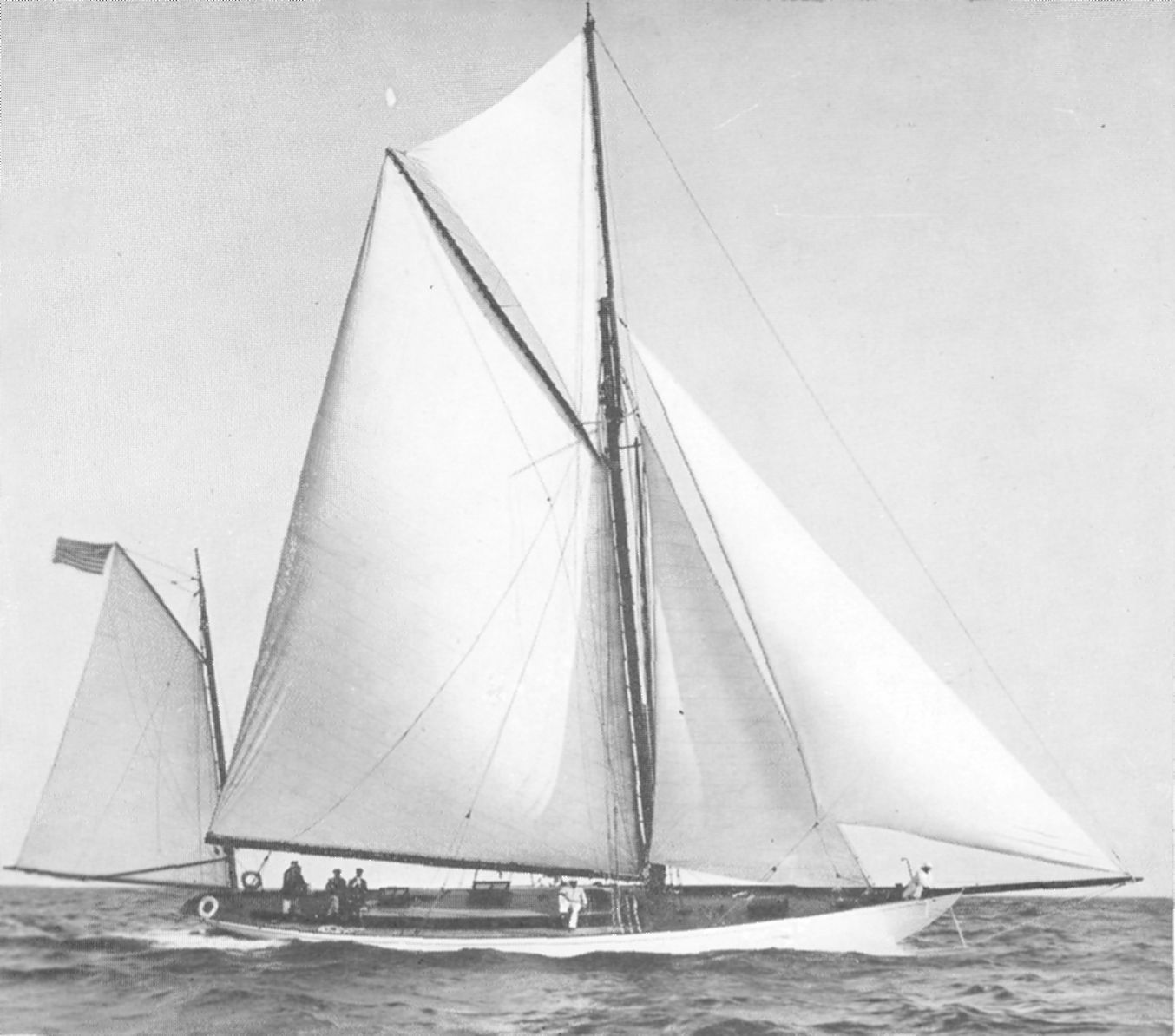

About 1875 he experimented with anti-fouling bottom paints and is credited with inventing mercurial anti-fouling paint, but I must mention that Charles Frederick, the father, as well as Charles Frederick, the brother, and Captain Nat all developed different anti-fouling paints of quite different formulae and color, two or three of which are now manufactured by various paint manufacturers.